By Emily Wright, Jay Barchas-Lichtenstein, Samuel Jens & Amy Mitchell

Introduction

Attacks against journalists are on the rise worldwide. In 2024, at least 124 journalists were killed, making it the deadliest year for the press on record. Globally, press freedom is under attack from legal, judicial and violent tactics. Journalists are facing surveillance, restrictive laws and strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), along with internet shutdowns and repressive laws and — sometimes — death. Journalists, especially women and minority groups, also endure increasing online harassment and cybersecurity threats. These include sexual harassment, doxxing, malware and deepfakes, with digital harm often leading to physical harm.

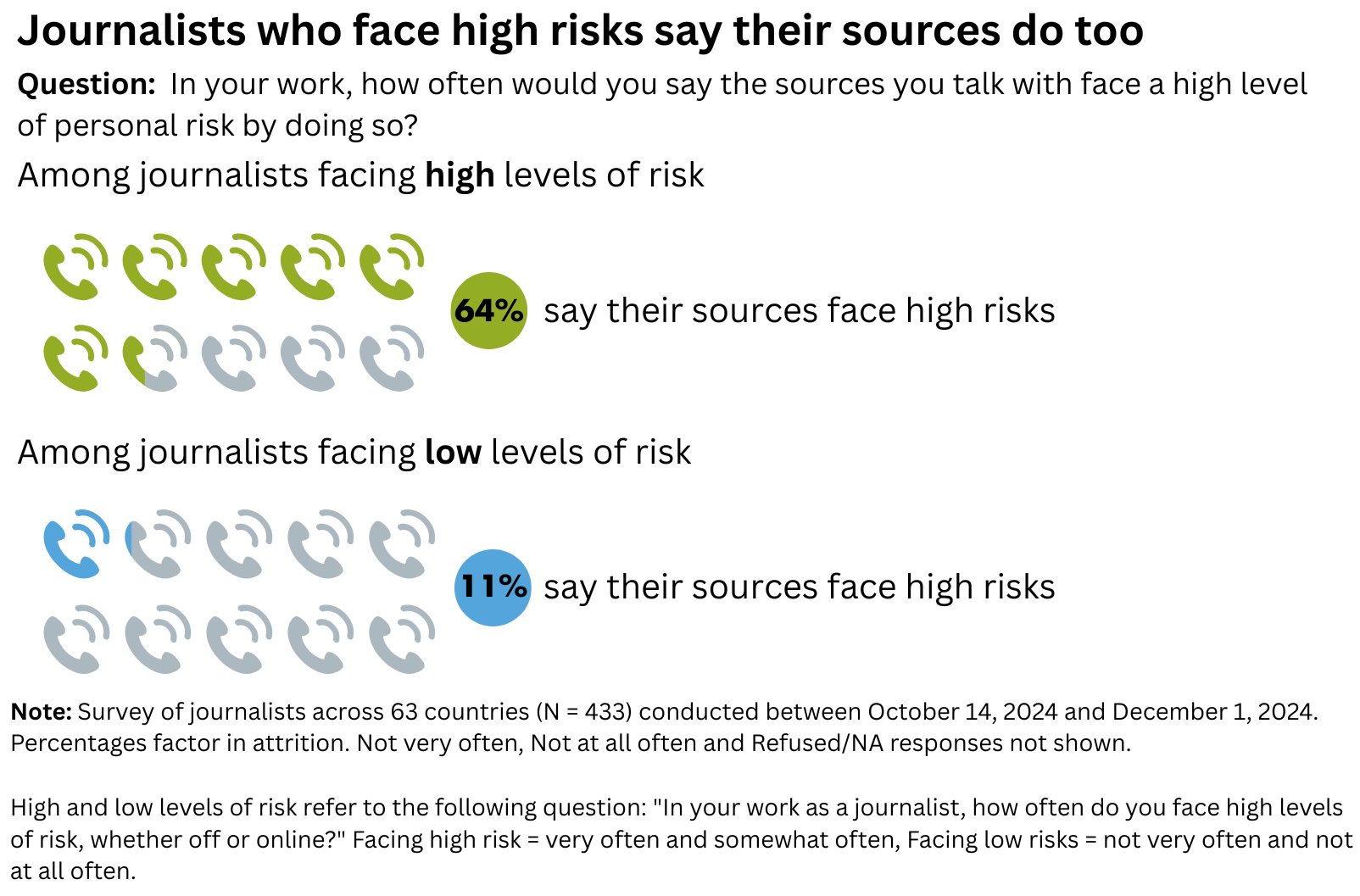

CNTI’s own research shows that risk doesn’t just impact the newsroom: 64% of journalists facing high risks 1say their sources do, too, while 11% of journalists facing low risks say their sources face high risks.

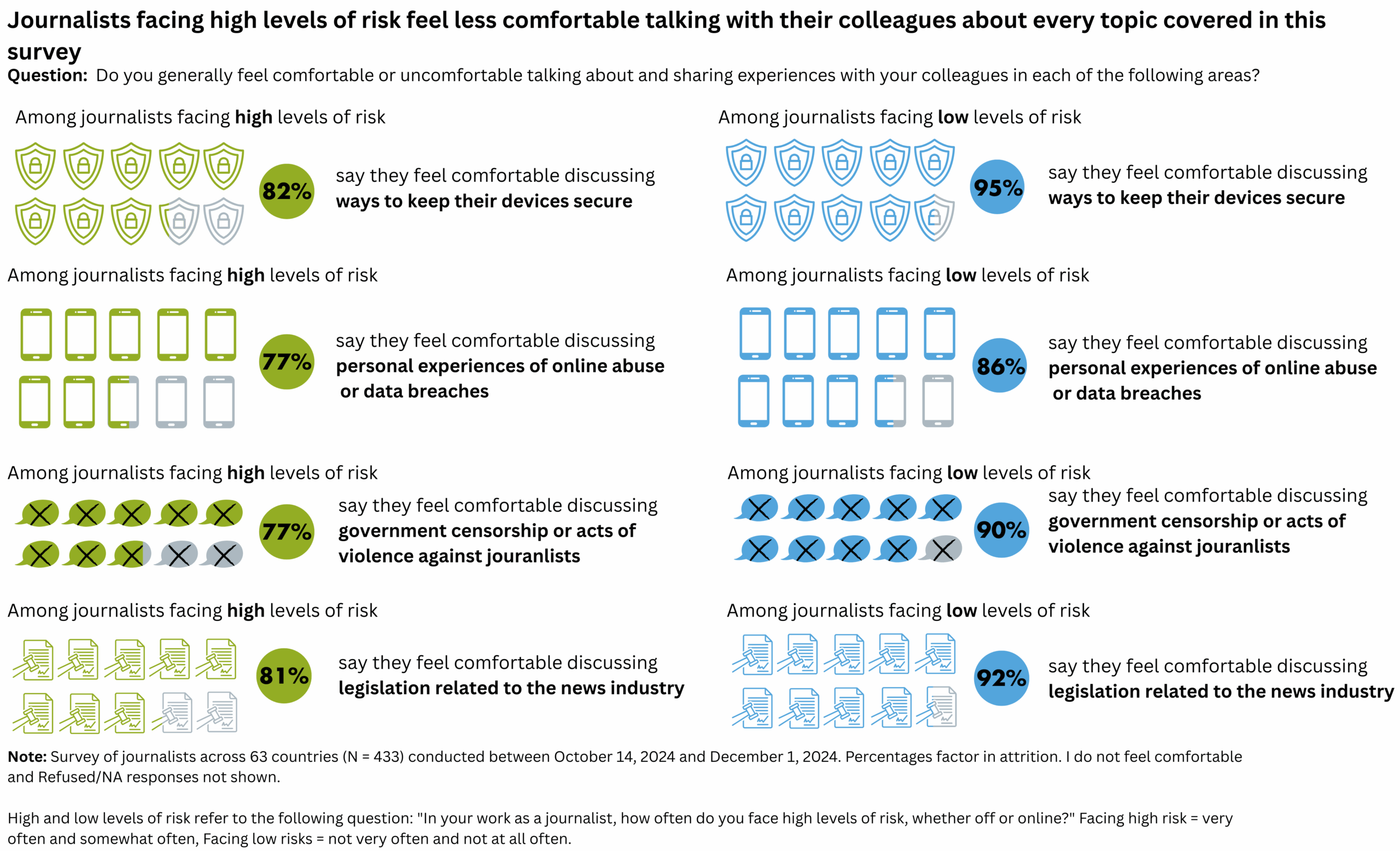

Journalists facing higher levels of risks do not report receiving higher levels of support to deal with these threats. Rather, all journalists perceive their news organizations to be paying similar amounts of attention to risks and that their newsrooms are similarly prepared to address online abuse. Journalists facing high risks say they feel less comfortable discussing these issues with their colleagues.

News organizations have an opportunity to increase engagement on these issues. By actively addressing these challenges and supporting the adoption of robust safety and security measures, they can help journalists work more safely and effectively. This support enables journalists to focus on their reporting rather than on the risks they face.

How we did this study

CNTI partnered with journalism organizations in several continents to share the survey with their members. Surveys are a snapshot of what people think at a particular moment in time. This data was collected between October 14, 2024 and December 1, 2024, which means they highlight the perspective of journalists around the world during that time frame. These data reflect the responses collected from 433 journalists across 63 countries. More details on the survey of journalists are available in the “About this study” page, and full questions and results are available in its topline.

Out of the 433 responses, 358 were submitted before the U.S. election on November 6, 2024. While President Donald Trump’s prior administration and campaigns were marked by frequent verbal attacks and threats against the press, the opinions of journalists expressed in this survey do not account for the recent actions of the current U.S. administration.

As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI.

Risks carry through to sources

Journalists facing high levels of risk are far more likely to say their sources also face high levels of risk, with 64% expressing this concern compared to 11% among journalists facing lower risks. This finding highlights that risks associated with exposing and sharing information are not limited to journalists themselves. When the public fears speaking with journalists due to potential repercussions, it can severely undermine the integrity and openness of the information environment.

Journalists are facing harassment from the public and the government, often through the use of technology

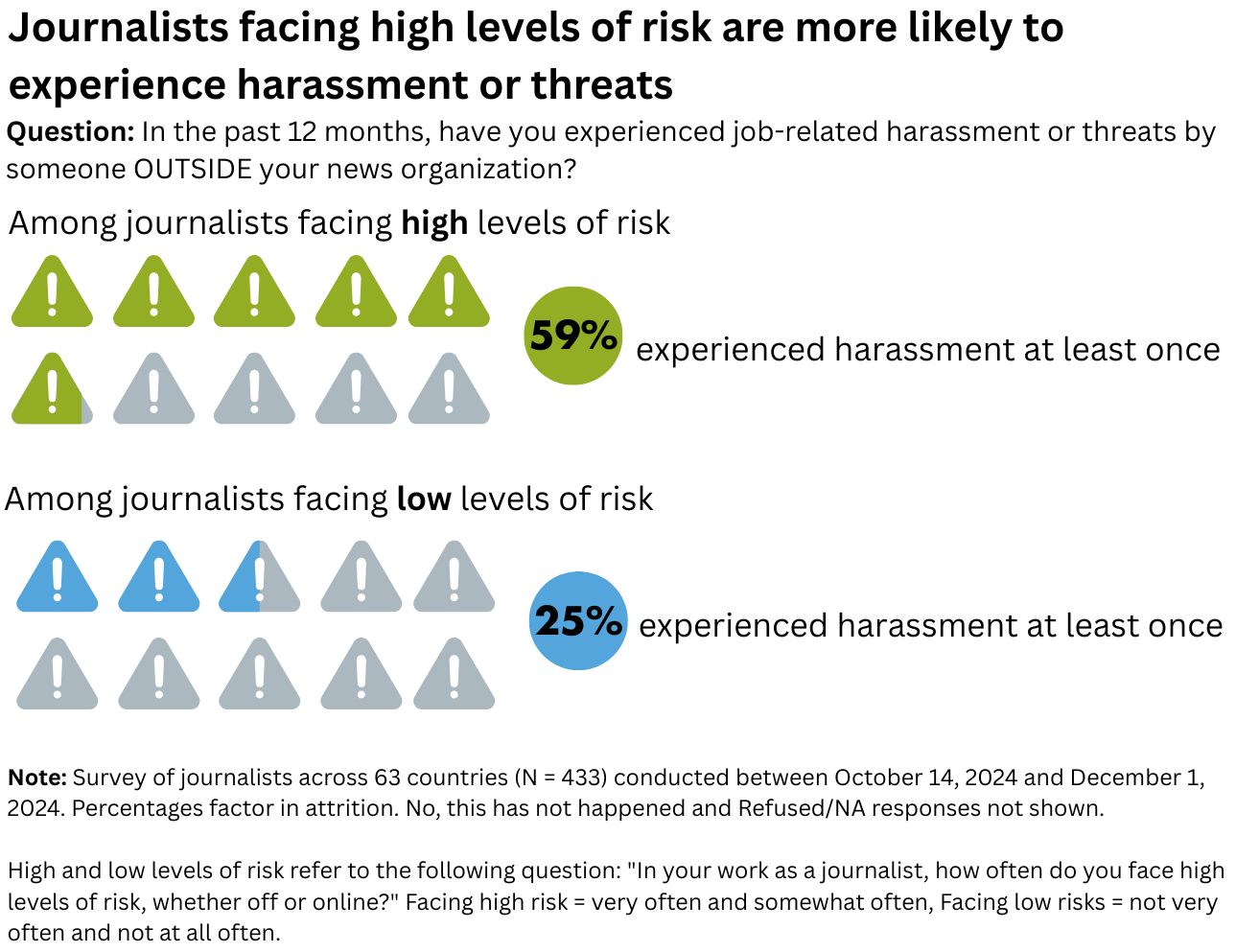

The risks journalists face are well documented and continue to grow. Our findings confirm that the journalists who report feeling unsafe are facing significantly higher levels of job-related harassment.

Those experiencing high levels of risk are more likely than those experiencing low levels of risk to have experienced harassment. This is true for every type of harassment covered in the survey, including threats of legal action (39 vs. 15%), physical harm to themselves (30 vs. 7%), exposure of private information (26 vs. 7%), sexual or gender based-harassment (24 vs. 6%), threats of financial harm (22 vs. 6%), racial or ethnic harassment (20 vs. 3%) and threats of physical harm to their family (18 vs. 1%)2.

Journalists experiencing high levels of risk are also more likely to have experienced government overreach than their colleagues. This is true for every form of overreach covered in the survey: receiving direct complaints about their content (48 vs. 25%), being denied access to a government hearing or other official event (39 vs. 24%), censorship (35 vs. 14%) and being arrested, detained, or imprisoned by the government or an affiliated group (9 vs. 2%).

Journalists facing high risks do not feel more supported by their news organization than their peers

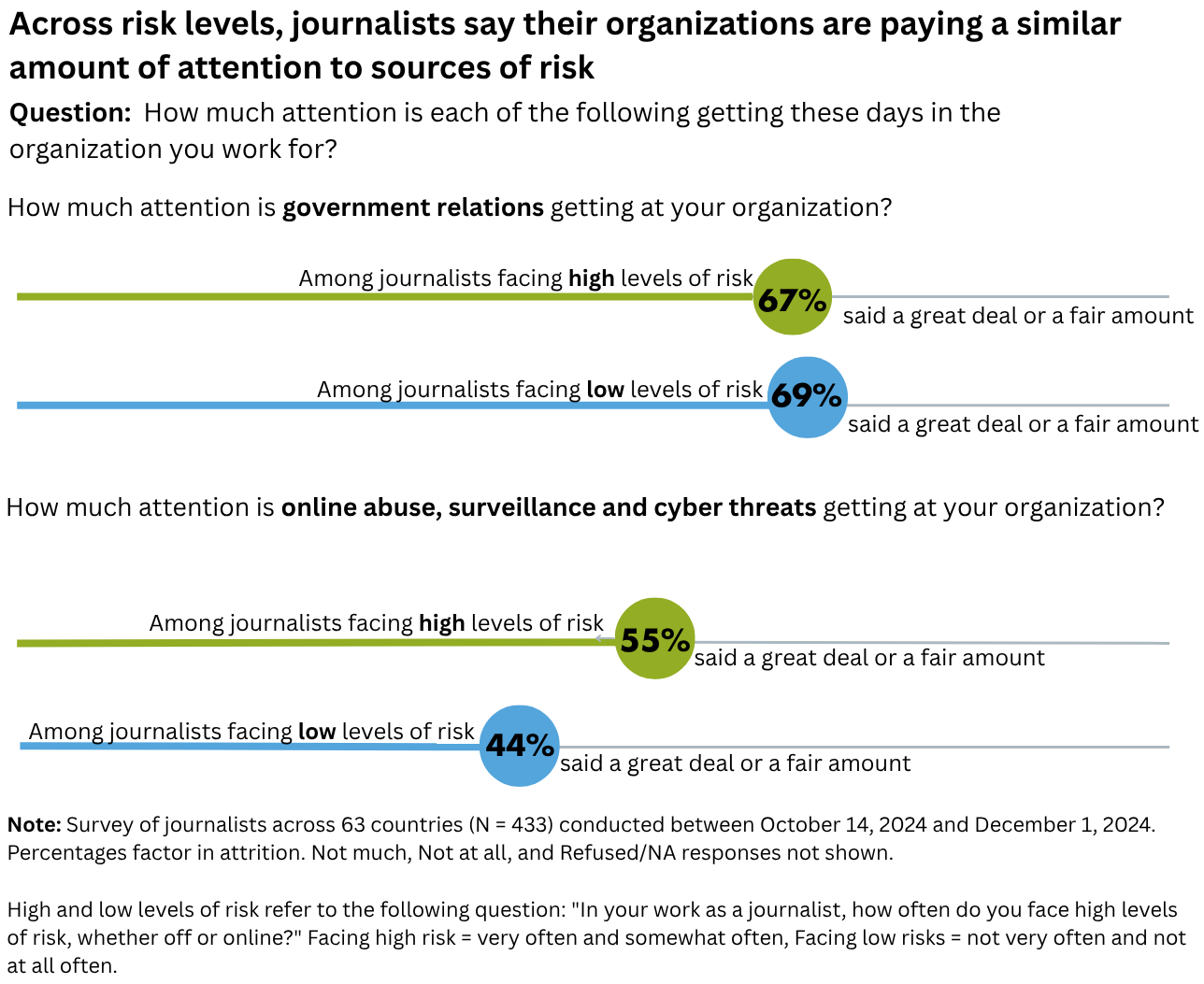

Despite facing different levels of risk, our data shows that journalists perceive their news organizations to be paying similar amounts of attention to relationships with the government and online abuse, surveillance and cyber threats. While two-in-three journalists say their organization is paying attention to government relations, about half say the same about online abuse, surveillance and online threats.

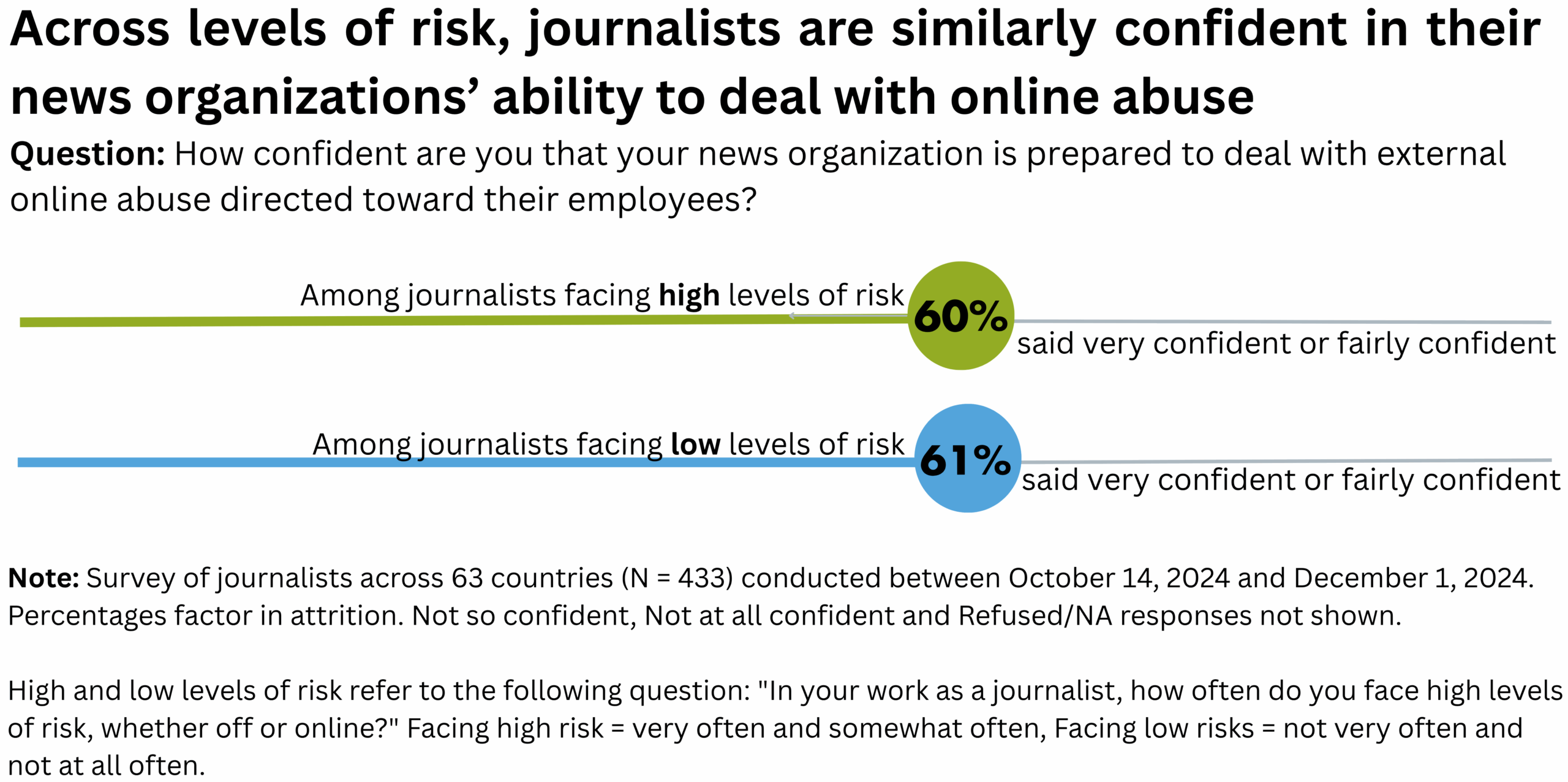

About six in 10 journalists are confident that their organizations are prepared to deal with external online abuse directed toward their employees. That’s true whether those journalists are facing high or low risks. Although a majority of both groups perceive their organizations as being prepared, four in 10 respondents lack this confidence.

Journalists facing high risks feel less comfortable than journalists facing low risks in talking to colleagues about topics related to their safety. That said, strong majorities of all journalists surveyed do still feel comfortable discussing all four topics with colleagues generally. When it comes to handling online abuse, surveillance and cyber threats, the journalists surveyed indicate there is room for newsrooms to increase both the amount of attention paid and improve their ability to address online abuse.

For the most part, all respondents take similar security precautions, but when it comes to being informed, journalists facing high levels of risk are more likely to feel very informed about journalists facing online harassment around the world than their peers who face lower risks (25 vs. 14%).

Why this matters

Journalists around the world consistently report that they feel unsafe as they confront serious threats, ranging from harassment and surveillance to government overreach and censorship. Journalists who are facing high risks believe their sources are, too. When the public is unable or is afraid to share information due to potential consequences, there can be severe negative impacts on the information environment.

Our findings suggest that journalists perceive that their news organizations could be doing more to support them. Specifically, about half of all journalists say that their organization is paying at least a fair amount of attention to online abuse, surveillance and cyber threats. About two-thirds say the same for government relations. Journalists facing the highest levels of risk are not only more exposed to threats, but they are no more likely to adopt protective security practices than those who do not face these risks.

Additionally, journalists who are facing high levels of risk are less likely to feel comfortable discussing safety concerns or experiences with their colleagues. This can lead to isolation and inhibit them from sharing experiences and strategies to improve protection.

Varying levels of comfort in discussing risks, along with insufficient institutional support, leave journalists exposed and less empowered to respond effectively to the threats they face.

TThis research underscores the urgent need to strengthen safety and security practices across the journalism profession. Not only is this vital for journalists, but also for continuing and improving free and independent media globally. Better supporting journalists who face high risks ensures that they are able to inform the public, hold power to account and contribute to the defense of democracy.

About this study

Why we did this study

This project is part of CNTI’s broader Defining News Initiative, which seeks to understand how journalism is perceived by audiences and journalists today. Access to information is not just important for its own sake; it makes democracy possible.

The journalist data in this article are a subset from a larger global survey, What It Means to Do Journalism in the Age of AI: Journalist Views on Safety, Technology and Government.

How we did this study

How we recruited participants

Surveys are a snapshot of what people think at a particular moment in time. CNTI partnered with journalism organizations on multiple continents. The questionnaire was crafted with input from partner organizations who knew the current situations and challenges of their members across various country contexts. These partner organizations also shared the survey with their members and can be found here.

CNTI collected responses between October 14 and December 1, 2024. This data highlights the perspective of journalists around the world during that time frame. The data reflects the responses of 433 journalists across 63 countries, with 256 respondents (59%) coming from three countries: Mexico, Nigeria and the U.S. Because no global census of journalists exists, no survey can be “fully representative” of all journalists.

How we addressed attrition

The survey was lengthy (with an estimated completion time of 20 minutes) and consisted of five distinct sections on different topics. The survey was broken into sections, and we treated each as a drop-off point: that is, if a respondent answered at least one question within a section, non-responses were treated as true non-responses. Respondents who answered no questions within a section were not included within the section’s N.

For transparency, topline tables include both percentages of the full survey N (Percent) as well as percentages of the section N (Valid Percent).

How we tested for statistical significance

Respondents were asked, “In your work as a journalist, how often do you face high levels of risk, whether off or online?” This report compares answers between journalists who answered (1) “very often” and “somewhat often,” or (2) “not very often” and “not at all often” for questions about government relations and online harassment and security. To test for statistical significance, responses were compared using Chi-squared proportion tests. We used a standard threshold of p < 0.05 for assessing statistical significance. Differences mentioned in the report text are statistically significant.

How we protected our data

CNTI did not collect any identifiable information that risked the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Data collection was supervised by CNTI staff only. The survey included individual-level information such as gender and the country where one worked and resided. It would be very difficult to identify study participants because CNTI did not collect their personal contact information or contact participants directly and the participants’ personal information was not shared by the partner organizations.

The data is securely stored in an encrypted folder, which is only authorized to the core research team at CNTI. More information about how each survey was administered may be found here.

- In our 2024 survey of 433 journalists around the world, about one-third (37%) of respondents confirmed that they are facing high levels of risk. ↩︎

- We only asked these questions of people who said they had experienced job-related harassment. ↩︎