By Emily Wright, Jay Barchas-Lichtenstein, Samuel Jens, Nick Beed, Amy Mitchell & Utsav Gandhi

In late 2024, we asked the public in Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the United States for their thoughts on news, journalism and journalists. Our public survey included open-end responses which were analyzed to understand how people view journalists. These four countries were chosen to represent a diversity of both media environments and geographies.

Our analysis of their responses to open-ended questions reveals that:

- Strong majorities of the public in all four countries use favorable rather than unfavorable terms to describe traits of journalists.1

- In multiple countries, the people who have negative views of journalists tend to also possess negative perceptions of the wider news ecosystem and/or conservative political leanings.

How we did this study

In 2024, CNTI conducted a survey with representative samples from four countries: Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the United States. (Brazil and South Africa are considered part of the Global South, while Australia and the United States are in the Global North.)

We asked two open-ended questions:

- Traits: All respondents were asked, “Thinking about people who produce journalism, what is the top trait or traits that come to mind?” We received 816 codable answers from Australia, 726 from Brazil, 606 from South Africa and 742 from the U.S.

- Definitions: Those who said yes to a closed-ended question (“Thinking about news and journalism, do you see journalism as something that is different from news or not?”) were encouraged to elaborate in response to “In just a few words, what is it that makes journalism different from news?” We received 603 codable answers from Australia, 467 from Brazil, 300 from South Africa and 536 from the U.S.

Four coders developed the codebook for each question through discussion and several rounds of preliminary coding. Then each country’s responses were coded by two coders, who resolved disagreements via discussion, conferring with the other coders as needed.

Data constraints:

- The full samples were nationally representative, but the set of codable responses in each country may not be. Percentages reported here are generally out of people with codable responses to open-ended items, not out of the full sample. They are weighted for consistency with prior reports.

- Responses varied greatly in length, and could receive multiple codes.

Comparisons:

- CNTI conducted a concurrent survey with journalists, in which we asked related questions. We make comparisons here with their responses, which were analyzed in detail in a prior report.

As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI.

See About this study for more details about the process.

ACROSS ALL FOUR COUNTRIES, MOST PEOPLE NAME POSITIVE TRAITS WHEN ASKED ABOUT JOURNALISTS — BUT CONSISTENT MINORITIES EXPRESS CONCERN ABOUT JOURNALISTS’ ETHICS

Around the world, the public has ambivalent views of journalism. CNTI wanted to know what they think about the people who create it. We asked respondents in Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the U.S. to share the top traits that came to mind when they thought about people who produce journalism.

Across all four countries, strong majorities used positive words and phrases when asked to name top traits that come to mind when thinking about people who produce journalism. Many in Australia, Brazil, and the U.S. described journalists as having clear ethical standards and being committed to verifiable facts. At the same time, about one-in-ten people in these same countries indicated that journalists do not have ethical principles.

In three of the four countries studied, most people who answered the question say that journalists are ethical, rely on verifiable facts or both

In Australia (45%), Brazil (38%) and the U.S. (44%), respondents were mostly likely to list traits that indicated that journalists have clear ethical standards. Traits indicating a reliance on verifiable facts were the second most common — 23% of Australians, 22% of Brazilians and 31% of Americans mentioned it. Responses from these three countries are similar to what we heard from journalists, although journalists emphasized verifiable facts slightly more often than ethics.

The positive ethical traits most frequently mentioned by Australians, based on simple counts of individual words and word stems included “honesty,” “integrity” and the absence of “bias” (or, occasionally, “awareness” and “transparency” regarding biases). Americans used the same words — “honesty” and “integrity” — frequently to describe ethics. In Brazil, on the other hand, “impartiality” stood out as a common word. Brazilians also frequently attributed “seriousness” to journalists, although it rarely appeared in responses from any other country. (In Brazilian Portuguese, describing a person as “sério” connotes integrity and decency more than somberness or lack of humor.)

Among Brazilians and Australians, the word “truth” was a frequent indicator for relying on verifiable facts, while in the U.S. “fact” was about equally common. The language of “credibility,” “accuracy” and “reliability” came up across countries as well.

On the other hand, no single trait was mentioned by a clear plurality of South Africans. Roughly comparable numbers of people mentioned that journalists rely on verifiable facts (13%), have clear ethical standards (18%), have grit and work hard (17%), have mental acumen (21%) and communicate complicated topics clearly (16%).

Consistent minorities see journalists as lacking ethical principles

Among those who offered less positive descriptions when asked what tops their list when thinking about journalists, the most common responses had to do with a lack of ethics. About one-in-ten Australian (12%), Brazilian (12%) and U.S. (14%) respondents described journalists as unethical. In all three countries, the absence of objectivity was the most common complaint among those who said that journalists are unethical in one way or another.

In Australia, those who found journalists to be unethical frequently described them as “biased” and “opinionated,” “activists” and “liars” who have an “overarching agenda or world view that their published works are viewed through.” Brazilians who viewed journalists as unethical primarily described them as “biased” or “political,” but some also mentioned other ethical failures, such as “hypocrisy,” “lying” and “financial interests.”

“Information that’s very partial; especially in this political moment; the mess the country is in; no one understands; things are too one-sided, without a filter; we’re suspicious of everything; it’s very complex; we might go crazy from here on.” (Brazil)

“I would like to think of it being ‘honesty’, but lately I believe they are more ‘dishonest’ and do not report the truth,” (US)

“They should be neutral, but often sneak their slant in.” (U.S.)

While infrequent, money and profit reflected another striking thread among those who were concerned about journalists’ ethics.

“They make the story say what is needed for money.” (Australia)

“They sell a lot of media, selling what the media wants. Not everything is apologised for and they only sell what’s interesting to them.” (Brazil)

“Bigger the story. The bigger the pay.” (U.S.)

In a similar vein, in all four countries about 5% of people said that journalists do not rely on verifiable facts. Many of these responses were also coded as “unethical.”

Journalists also name facts and ethics as their top traits — and do not have concerns about a lack of ethics

The public is largely in sync with journalists on key journalistic traits. When CNTI asked a similar question in our 2024 survey of journalists, the same two traits came to the forefront. In that survey, journalists mentioned reliance on facts (49% of surveyed journalists) and ethics (41% of surveyed journalists) with roughly equal frequency.

Journalists differed from the public in not raising concerns about a lack of ethics. The negative perceptions we heard from journalists were few and far between, and largely focused on the danger of practicing journalism today or on poor financial compensation.

NEGATIVITY ABOUT THE NEWS ECOSYSTEM IS LINKED TO NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS OF JOURNALISTS. SO IS POLITICAL IDEOLOGY.

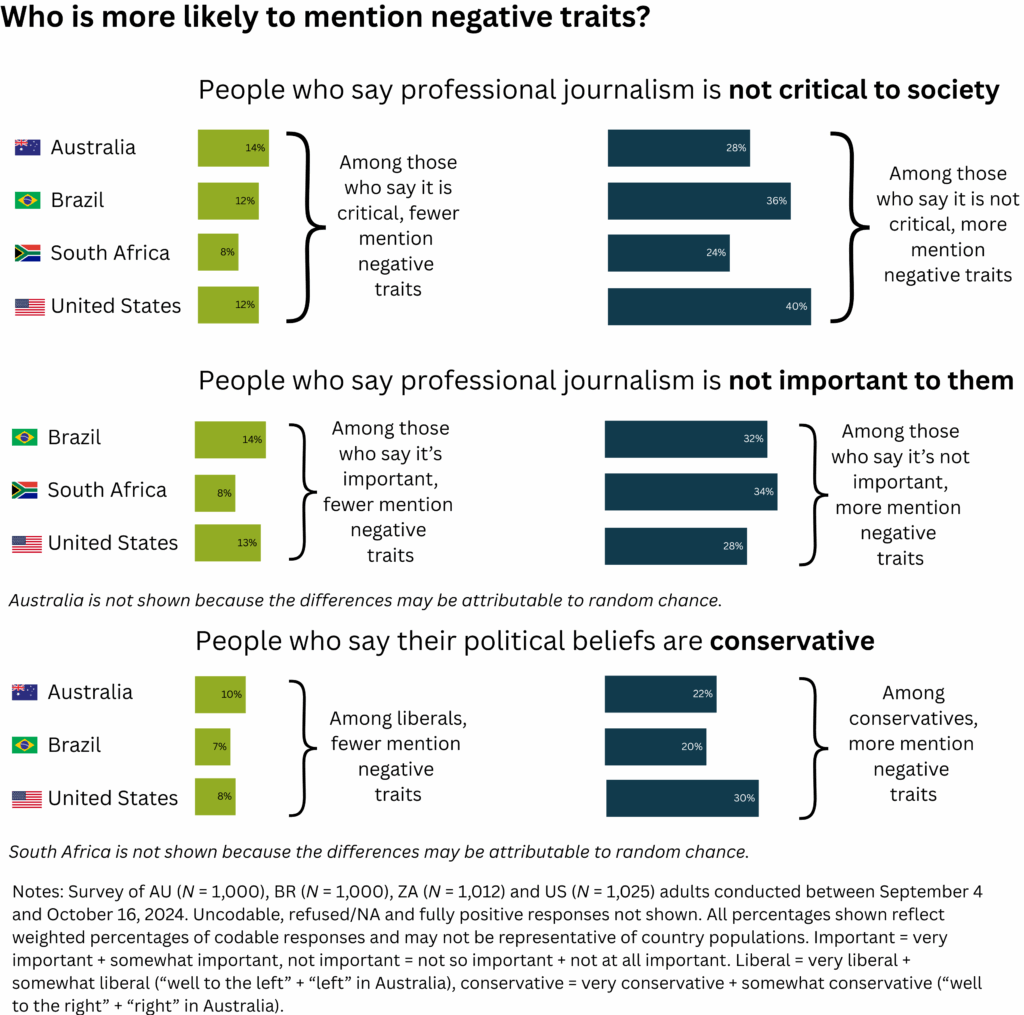

A notable minority in all four countries, between 10% (South Africa) and 20% (Brazil), associated journalists with at least one negative trait. To understand what drives these negative perceptions, we analyzed their responses in connection with other survey questions. This comparison revealed a connection between those with negative perceptions of journalists and those with negative views of the broader news ecosystem and/or conservative political ideologies.

In all four countries, respondents who indicated that mainstream news organizations2 do not play a critical role in an informed society were more likely to list negative traits about journalists, compared with people who do see them playing a role.

In three countries (Brazil, South Africa and the U.S.), people who said it is not important for them to get news from mainstream news organizations were more likely to give a negative response when asked about the traits of journalists. In Australia, responses were consistent, no matter how people answered this question.

In Australia, Brazil and the U.S., members of the public who consider themselves to be very conservative or conservative were more likely to include negative traits compared with those who consider themselves to be very liberal or liberal. These partisan or ideological differences may be linked to the global phenomenon of political attacks on journalism: In both Brazil and the U.S., conservative leaders have repeatedly made highly visible comments disparaging journalists and mainstream media in recent years. In South Africa, meanwhile, ideology did not seem to make a difference. (Nothing comparable has happened on the same scale in either Australia or South Africa.)

Majorities view journalists positively — even across ideology

When asked what traits of journalists come to mind, publics across the four countries are largely positive. Even among those who are more negative about various aspects of the information environment, clear majorities view the people who produce journalism positively. While we do find evidence of political ideology being associated with views of journalists — those who self-report having a conservative ideology are more negative than those who report being liberal — majorities of both ideological groups still provide positive traits when asked to think about journalists. Overall, people in each of the four countries view journalists positively, which provides an opportunity for the journalism industry to continue to build trust and explain the relevance of the journalistic process to the public.

FOR THOSE WHO SEE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN JOURNALISM AND NEWS, JOURNALISM BUILDS ON NEWS

CNTI’s 2024 public survey also explored if and how people in the four countries distinguish between journalism and news. About two-thirds of Australians and Americans said they are different, as did about half of Brazilians and 40% of South Africans.

Of the people who say there is a difference between news and journalism, strong majorities in Australia (76%), Brazil (70%) and the U.S. (82%) describe journalism as going beyond news in some way. Of the people in South Africa who say there is a difference, four-in-ten (40%) also expressed this view. But there was a lot of variation about precisely what journalism adds to news. Respondents’ answers suggest that journalism is news with opinion, rigor, context, facts, storytelling and/or breadth.

Some respondents saw journalism and news as inseparable and perceived news as the content and journalism as the professional activity. Others saw journalism and news as complementary, both meeting information needs, but through different topics or different mediums.

Their definitions of both news and journalism align closely with findings from our earlier focus groups where participants described journalism as a robust process of research and storytelling informed by ethical values and news as recent, accurate and socially relevant. The definition of news also aligns with research from the Pew Research Center, which shows that Americans view news as factual, current and “important to society.”

The public did not draw the same direct connections between journalism and civics and democracy as journalists did in CNTI’s 2024 journalist survey, but the traits they mentioned most frequently are traits that enable the civic function of journalism.

About this study

Why we did this study

This report is part of CNTI’s broader “Defining News Initiative” which examines questions surrounding this theme in policy, technological developments and the views of journalists, in addition to public perceptions. The data in this report explore the public’s perceptions of news, journalism and technology in four countries: Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the United States. These data were collected in parallel with a global survey of journalists.

CNTI was motivated by several overarching questions:

- How does the public navigate new ways of being informed?

- Where do they see journalism fitting in?

- How can journalism do a better job of communicating its unique value?

Answers to these questions are central to better understanding the evolving information ecosystem. As CNTI learned in a series of focus groups last year in the same four countries, people are putting a lot of work into getting themselves up to speed on news. At the same time, many are actively tuning news out, expressing a sense that it is overwhelming. This research continues a series of CNTI reports that examines these ideas with a specific focus on the open-ended questions in the survey. CNTI’s first report, “What the Public Wants from Journalism in the Age of AI: A Four Country Survey,” was published earlier this year.

As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI. This project was financially supported by CNTI’s funders.

How we did this

CNTI’s survey questionnaire was developed internally by our research team and advisors in consultation with Langer Research Associates. Focus groups were initially run in each of the four counties which informed the development of the questionnaire. In addition to references made throughout this report, themes from these focus groups may be found in a series of essays available on CNTI’s website.

In partnership with Langer Research Associates, the data were collected through different vendors in each country:

- Australian data are from an Infield International RDD CATI/cell phone sample conducted from September 4 to October 1, 2024. The total sample size was 1,000 respondents. The design effect was 1.39 with a margin of error of 3.7 points. The survey was only available in English. All interviews were conducted by telephone, and the median interview length was 18 minutes and five seconds. There were 41 interviewers used by Infield International all of whom were trained. The sample collection age categories were: 18-24, 25-34, 45-54, 55-64 and 65+.

- Brazilian data are from an Inteligência em Pesquisa e Consultoria (IPEC) RDD CATI/cell phone sample conducted from September 13 to October 3, 2024. The total sample size was 1,000 respondents. The design effect was 1.67 with a margin of error of 4.0 points. The survey was only available in Brazilian Portuguese. All interviews were conducted by telephone, and the median interview length was 16 minutes and 49 seconds. There were 76 interviewers all of whom were trained. The sample collection age categories were: 18-29, 30-44, 45-59 and 60+.

- South African data are from an Infinite Insight RDD CATI/cell phone sample conducted from September 23 to October 16, 2024. The total sample size was 1,012 respondents. The design effect was 1.48 with a margin of error of 3.7 points. The survey was available in English (n = 811), Zulu (n = 138), Sesotho (n = 24), Sepedi (n = 17), Setswana (n = 12) and Xhosa (n = 10). All interviews were conducted by telephone, and the median interview length was 19 minutes and 17 seconds. There were 47 interviewers all of whom were trained. The sample collection age categories were: 18-24, 25-34, 35-49, 50-64 and 65+.

- United States data are from Ipsos’s probability-based online KnowledgePanel® and was conducted from September 12-21, 2024. A total of 1,670 panelists were initially selected and 1,053 completed the survey. A total of 28 respondents were removed during the quality control process, yielding a final sample size of 1,025 respondents. The design effect was 1.13 with a margin of error of 3.3 points. The survey was available in English (n = 983) and Spanish (n = 42). All surveys were self-administered online, and the median interview length was 10 minutes and 23 seconds. The sample collection age categories were: 18-29, 30-44, 45-59 and 60+.

Technical reports from the survey vendors are available upon request from info@cnti.org.

How we coded open-ended questions

All respondents were asked about the traits of journalism producers: “Now thinking about people who produce journalism, what is the top trait or traits that come to mind?” We received 816 codable answers from Australia, 726 from Brazil, 606 from South Africa and 742 from the U.S.

Respondents were also asked,“Thinking about news and journalism, do you see journalism as something that is different from news?” If they responded “yes,” they were asked, “In just a few words, what is it that makes journalism different from news?” We received 603 codable answers from Australia, 467 from Brazil, 300 from South Africa and 536 from the U.S. Answers were variable in length, detail and the kind of relationship they described.

Both open-ended questions were coded by a team of four researchers. Responses for each country were coded by a unique pair of researchers and no two researchers coded the same two countries within a given open-ended question. The two researchers who had coded related items in CNTI’s survey of journalists and developed the initial coding scheme never co-coded for this report.

The research team followed an iterative process in which an initial subset of responses were coded to assess the codebooks (presented below) and discuss options for other categories.

Researchers independently completed their coding although they discussed questions that arose during their analysis via online messaging. The country pairs of researchers met to discuss any coding disagreements after each researcher finished their own coding. Coders used informed judgement when assessing responses that lacked clarity. All discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two participating coders and, where necessary, the larger group of four coders.

All results shown in the main report use the survey weights (described below). The toplines present both the weighted and unweighted frequencies. The results also only show the share of responses in a given category as part of the codable responses. In effect, the total number of responses we include in analyses are only those the research team could code.

Researcher positionality

The four researchers who participated in the coding process are all from the U.S. While three of the four have lived outside the U.S. for extended periods of time, those experiences do not include Brazil, South Africa or Australia.

Coding the traits of journalism producers

The initial trait categories were developed in our analysis of data from journalists, then we identified additional keywords from the larger data set of the public survey responses. For the public survey responses, we also considered valence (i.e., emotional direction) since a number of responses focused on the absence of identified traits rather than their presence.

Coders analyzed each country’s responses separately before coming together to discuss any disagreements. Both researchers needed to agree on a category to finalize the coding. Coders used informed judgement when assessing responses that lacked clarity.

The final codebook consists of nine (9) categories that capture the range of responses participants provided when contemplating the traits of journalism producers.

Here is a list of words and attributes that fit into each category:

| Category | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Journalists rely on verifiable facts | This category describes the idea that journalism producers focus on facts and verification. They provide accurate, credible and reliable information to audiences. Common keywords were: Accuracy, accurate, correct, credibility, credible, evidence, fact, factual, fidelity, precise, precision, reliability, reliable, trust, trustworthy, truth, truthful, valid, verification, verified, verify | Common keywords that represented negative valence include: Clickbait, fake news, lies |

| Journalists have clear ethical standards | This category describes the idea that journalism producers exhibit ethical behavior and are honest. They display transparency, accountability and professionalism in their work. Common keywords were: Accountability, accountable, accredited, character, commitment to [community/public], consistent, ethical, ethics, honest, honesty, incorruptible, independence, independent, integrity, professional, public interest, qualified, reputable, respectability, sensitive, serious, sincere, sincerity, standards, transparency, transparent, watchdog | Common keywords that represented negative valence include: Clickbait, fake news, liars, references to money |

| Journalists are objective (subset of “Journalists have clear ethical standards”) | This category describes journalism producers as objective in their work. They display fairness, impartiality and objectivity, and their content is balanced. Objectivity is a subset of ethical standards. Therefore, any response coded in the objectivity category was also included in the ethical standards category. Common keywords were: Balance, balanced, fair, fairness, impartial, impartiality, neutral, neutrality, not having a preformed opinion, objective, objectivity, unbiased | Common keywords that represented negative valence include: Activism, agenda (as in producers have one), bias, opinionated, sensationalism, spectacle |

| Journalists are analytical | This category describes journalism producers as analytical with a desire to investigate, research and seek information. Many alluded to a rigorous process with the goal of uncovering information. Common keywords were: Analysis, analytical, attentive, context, critical, cynical, depth/deeper, dig, gather, investigate, investigation, logic, logical, observant, perceptive, research, rigor/rigorous, skeptical | |

| Journalists have “grit” and work hard | This category presents journalism producers as brave, determined and persistent individuals who work hard and display grit and passion. Common keywords were: Ambitious, assertive, audacious/audacity, boldness, brave/bravery. commitment (without modifier), confidence, courage, courageous, daring , dedication, detail/detailed, determination/determined, diligent, driven, focus, grit, hard-working, intense/intensity, painstaking, passion, perseverance, persistence, persistent, preparation, resilient, resourceful, responsibility/responsible, stubborn, tenacious/tenacity, thorough | |

| Journalists have mental acumen | This category describes journalism producers as curious, educated and well-informed people who provide insightful, worldly content to audiences. Common keywords were: Competence, cultured, curiosity/curious, educated, inquisitive, insight/insightful, intelligent, knowledgeable, open minded, perspicacious, smart, study (in the school/education sense), thoughtful, well-informed, wisdom, witty, worldly | |

| Journalists can communicate complicated topics clearly | This category describes journalism producers as articulate, engaging and innovative individuals who communicate topics to audiences in a way that is creative yet straightforward. Common keywords were: Articulate, clarity, clear, coherent, communicate, creative/creativity, direct, eloquent, engaging, informative, innovative, story, straightforward, upfront, write | |

| Journalists provide work that is timely and proximate to happenings on the ground | This category describes journalism producers as people who are on the scene and provide timely, relevant information that includes sources/witnesses. It also encapsulates how journalism producers interact with others by listening and how they are readily available to complete their work. Common keywords were: 24/7, adaptability, at/on the scene, connection, deadlines, first hand, flexibility, immediacy/immediate, listen, perspective, relevant, source, speed, witness | |

| Other | The “other” category denotes responses that include traits which did not fit cleanly into the categories above. Examples include: Attractive, authentic, believable, bossy, charismatic, empathy, experience, extroverted, genuine, important, invasive, nosy, outgoing, pushy, quality, real, reputation |

The results for this open-ended question are shown in the table below.

| Traits of journalism producers | AU | BR | ZA | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journalists rely on verifiable facts | 23% | 22% | 13% | 31% |

| Journalists DO NOT rely on verifiable facts | 5% | 4% | 5% | 5% |

| Journalists have clear ethical standards | 45% | 38% | 18% | 44% |

| Journalists DO NOT have clear ethical standards | 12% | 12% | 5% | 14% |

| Journalists are neutral, impartial, objective and fair | 17% | 10% | 3% | 24% |

| Journalists are NOT neutral, impartial, objective or fair | 9% | 9% | 2% | 13% |

| Journalists are analytical | 10% | 4% | 10% | 10% |

| Journalists have “grit” and work hard | 11% | 11% | 17% | 14% |

| Journalists have mental acumen | 16% | 12% | 21% | 14% |

| Journalists can communicate complicated topics clearly | 13% | 11% | 16% | 10% |

| Journalists provide work that is timely and proximate to happenings on the ground | 4% | 3% | 7% | 3% |

Coding the differences between journalism and news

The final codebook reflects that when drawing comparisons between news and journalism, many discussed the idea that journalism adds a quality to news. Therefore, each country was reviewed again with the inclusion of “news +” categories that reflect this idea. Updating the codebook provided for a more comprehensive understanding of the differences between journalism and news.

The final codebook has 14 categories. The first category denotes whether the response was uninformative (i.e., the concepts are the same or there is a difference but it is unspecified). The next five (5) categories assess differences between journalism and news in which the two concepts are viewed as separate/distinct. The next seven (7) categories assess the common response that journalism adds a quality to news (news +). The final category (Other) serves as a catch-all for responses that did not fit cleanly into the previous 13.

The final codebook is presented here:

| Category | Coding considerations |

|---|---|

| Uninformative (concepts are either (1) the same or (2) different [but cannot be clearly coded]) | Responses received this code if they stated the two concepts, news and journalism, were either (1) the same or (2) different (but in an unspecified fashion). Coders reserved this decision for responses that were qualitatively different from those coded as NA because there was emphasis on a difference even if what the difference was could not be clearly decided or understood. A response that received this code did not receive any additional codes. |

| Process & Product | This code was used in cases where one concept referred to a process and the other referred to either the input or the outcome of that process. |

| Different Medium | Responses received this code if at least one of the two concepts includes a specific, unique form of communication that the other does not. Common media included online, radio, TV or print (i.e., newspapers or magazines). |

| Corporate vs. Individual | This code was used when one concept emphasizes a connection to business, financial interests or organizations versus a connection to people. Coders treated “the media” and “mainstream media” as a business collective and included responses that highlighted corporate interests or structures, such as “Sometimes, there are journalists who only speak according to what the company owner dictates.” |

| Different Topics | This code was used to denote if a response discussed news or journalism covering different topics and/or stories. Just because one concept provides more depth (see News + Depth) does not mean that they necessarily cover different topics |

| Sensationalism & Exaggeration | This code was used for responses that described either news or journalism in terms of sensationalism, exaggeration or dramatization in how it presented information, covered stories or discussed topics. |

| News + Breadth | Responses exhibited the idea that journalism includes greater breadth of coverage, job responsibility and/or roles than news. |

| News + Depth | Responses exhibited the idea that journalism includes greater depth, context and/or analysis than news. |

| News + Rigor | Responses fit the idea that journalism includes greater rigor, investigation, verification and/or ethics than news. References to research and professionalism were also included in this category. |

| News + Opinion | Responses exhibited the idea that journalism includes greater presence of opinion, personal views, perspective and/or bias. |

| Valence | Responses in the “News + Opinion” category received a secondary analysis to determine whether the overall valence was negative (e.g. “bias,” “spin” or “agenda”) or neutral-to-positive (e.g., “perspective”). |

| News + Truth | Responses fit the idea that journalism includes more truth, facts, credibility and/or accuracy than news. |

| News + Storytelling | Responses exhibited the idea that journalism provides greater storytelling, crafting, narrative and/or human touch than news. |

| Other | Responses that did not fit the categories above in whole or in part were reviewed manually. |

The results for this open-ended response are shown in the table below.

| Differences between journalism and news | AU | BR | ZA | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process & Product | 6% | 4% | 10% | 11% |

| Different Medium | 2% | 5% | 4% | 1% |

| Corporate vs. Individual | 6% | <1% | <1% | 3% |

| Different Topics | 8% | 4% | 6% | 9% |

| Sensationalism & Exaggeration | 3% | 2% | 1% | 2% |

| Journalism adds something to news | 76% | 70% | 40% | 82% |

| Journalism adds… | ||||

| Opinion… | 29% | 18% | 5% | 31% |

| …and that’s a negative thing | 12% | 13% | 2% | 13% |

| …and that’s a neutral-to-positive thing | 17% | 5% | 3% | 18% |

| Rigor & Ethics | 24% | 21% | 20% | 23% |

| Context & Depth | 21% | 13% | 8% | 27% |

| Truth & Facts | 8% | 18% | 7% | 10% |

| Storytelling | 6% | 2% | 3% | 8% |

| Breadth | 5% | 2% | <1% | 2% |

Coding the differences between journalism and news

After the open-ended questions were coded, we re-merged these data with the full quantitative survey data by each respondent’s unique identification number. Thus, we had a full data set of their survey responses and their open-ended responses categories.

Each country’s data were weighted using demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, education and macroregion). While each individual country used a different age breakdown for sample collection, we opted to recode the age breakdown into the following categories: 18-29, 30-44, 45-54 and 55+. These categories were used to ensure there were at least 100 weighted respondents in each group — South Africa has a younger population, especially compared with the United States’ older population.

We also applied the survey weights to analysis that include open-ended response categories. We include both the weighted and unweighted frequencies for the open-ended responses in the toplines. For specific questions about the sample frames, weighting procedures and/or additional survey details, please send an email to the research team at info@cnti.org.

How we tested for statistical significance

We analyzed the results using Chi-squared proportion tests to assess differences in responses between two countries. We used a standard threshold of p < 0.05 for assessing statistical significance. Differences mentioned in the report text are statistically significant.

How we addressed data quality in open-ended questions

Data quality in the open-ended responses received attention during the analysis phase of the project. CNTI worked with Langer Research Associates and country vendors to review what interviewers recorded from respondents’ open ends. Several anomalies and mistakes were found. Interviewer recordings of the open-ended responses were reviewed by the vendor and CNTI received updated data for both open-ended questions.

Researchers left individual responses as is and coded responses using informed judgement. Some non-standard orthography and typographical errors were easily interpretable. However, others were difficult to assess and were discussed by the research team. Any responses that could not be clearly understood were treated as uncodable and removed from the data set. Responses quoted in the report have been lightly edited to conform with standard orthography and punctuation.

We also examine results by country rather than as one total, because there may be a mode effect present in the survey results. The U.S. data were collected online, whereas the other three countries’ surveys were conducted through telephone, which may yield higher levels of social desirability responses in these locales. Research shows there is known variability in survey responses across countries and cultures regarding social desirability and acquiescence which may, in part, also be shaped by survey mode.

How we protected our data

Data collection was done by the country-specific vendors listed above. The survey included individual-level information such as age, gender, race, political ideology and macro-region. Survey data supplied to CNTI from the vendors did not include names or specific locations of respondents. Each respondent received an unique identifier.

It would be very difficult, if possible at all, to identify survey respondents because CNTI did not collect personal contact information or contact respondents directly. The survey data for this project are securely stored in an encrypted folder that is only authorized to the core research team at CNTI.

Toplines

Footnotes

- Throughout this report we use the term “journalist” for clarity, although we asked about “people who produce journalism” because we were trying to better understand how people understand the meaning of this term. See our focus group report for additional details. ↩︎

- Because we were trying to tease out differences between journalism and news, we avoided using those words whenever possible. In our survey questionnaire, we used the phrase “news organizations that employ reporters” as a proxy for traditional media companies to distinguish them from other kinds of content producers. ↩︎