TL;DR

Table of Contents

Overview

Over the last few decades, the widespread adoption and use of new communications technology have rapidly reshaped global information ecosystems. For journalists and news organizations, these changes have both empowered their work and presented new challenges. For the public, these technological and social changes have provided many more options, disrupting how news outlets have historically interacted with them. Concurrently, governments around the world are increasingly impinging on press freedom, weaponizing the law against journalists, while questions about revenue models and digital content valuation remain unsettled.

Social media platforms specifically have offered new opportunities to meet the public where they are, but have also put journalists on the receiving end of continuous legal threats and harassment.

Most recently, the convenience and expediency of AI tools1 can help individuals and teams produce more content — but these tools are resource-intensive, have shown potential for inaccuracy, and the opacity of their algorithms can leave journalists unsure about how their own work is being repurposed.

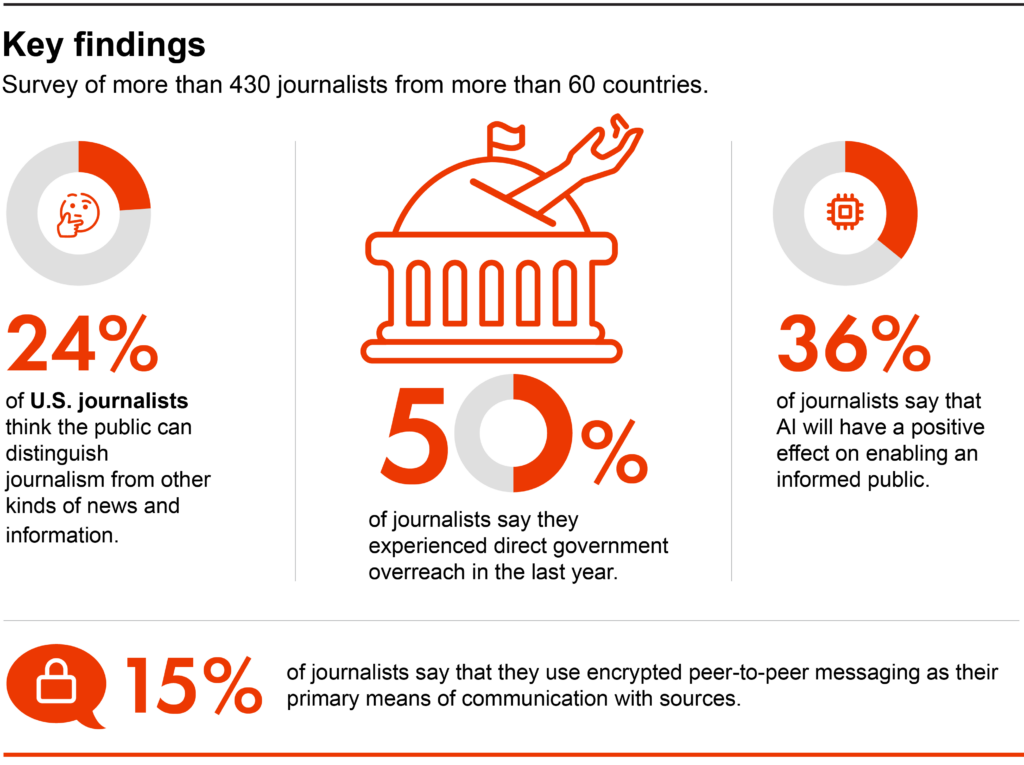

Surveys are a snapshot of what people think at a particular moment in time. We surveyed more than 430 journalists from more than 60 countries about government, technology, online harassment and what it means to be a journalist these days between October 14, 2024 and December 1, 2024. As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI. Here are some highlights of what we learned:

Journalists see a lot of value in their field, but they are unsure that value is being communicated well, leading to public confusion: U.S. journalists don’t think the public can identify what journalism is — or what it isn’t. About one-in-four U.S. journalists (24%) think the public can distinguish journalism from other kinds of news and information. Meanwhile, about half of Mexican journalists (48%) think the public can make a distinction, as do 70% of Nigerian journalists. And while professional training and institutions matter to journalists’ self-conception, most of them agree that people who are not journalists can produce journalism. (Read this section of the report.)

Half of the journalists surveyed (50%) have experienced direct government overreach in the last year. This may be why strong majorities (more than three-quarters) say it is inappropriate for the government to define journalism or journalists, and about half say their government exerts too much control over journalism. (Read this section of the report.)

Journalists believe technology is improving their work, but they are hesitant about AI: Two-thirds say that technology in general — and social media in particular — are having a positive effect on their work, although only one-third say the same about AI’s effect on the information landscape. Journalists in the Global South are more positive overall. (Read this section of the report.)

Serious risks are wide-spread: one-in-three face them somewhat often or more. All the same, preparation varies: Changing passwords and updating hardware and software on devices is done frequently — but journalists don’t necessarily communicate with sources through the most secure platforms. About 40% said they do both once every few months on average, and 30% or less say they did so once every few years or when the device stops working. And journalists in the Global North do both of these more often than their colleagues elsewhere. Meanwhile, 15% of journalists say that they use encrypted peer-to-peer messaging as their primary means of communication with sources. Strong majorities do feel comfortable discussing safety with colleagues and managers, including government censorship and personal experiences of abuse. (Read this section of the report.)

Finally, as a way to connect the dots across the different issue areas asked about, we asked an overarching question about seven current issues facing many news organizations today. The results provide valuable insight into journalists’ sense of field — and newsroom-wide priorities — which may not match newsroom leaders’ perspective. According to respondents, the long-standing issue of audience engagement continues to get the most attention inside news organizations with revenue streams and misinformation coming next. At the bottom: Online abuse.

This report addresses the information environment with a focus on four of the most pressing issue areas today, each of which deserves more research and conversation: definitions of news and journalism, relationships between news organizations and the government, technology and AI, and security and safety. While the report parses out these areas, there is a great deal of overlap, addressed across sections.

Read CNTI’s companion report based on surveys with representative publics in four countries.

Footnotes

- Given the lack of consensus about what "Artificial Intelligence" encompasses, we use the term broadly to refer to "sciences, theories and techniques whose purpose is to reproduce by a machine the cognitive abilities of a human being."While there is no agreed-upon technical definition, it's helpful to consider examples like Large Language Models (LLM), which are "trained" on data to recognize statistical patterns and use those patterns to generate plausible text. These kinds of models typically have too many parameters to be fully transparent or explainable, even for their creators. ↩︎

Share