TL;DR

Table of Contents

AI policy in the region

Several countries across East Asia and the Pacific have passed (or are actively considering) legislative proposals for regulating AI. Other countries have presented national strategies and guidelines, while some are relying on existing law. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has promoted an AI governance and ethics framework for companies looking to develop and deploy AI models in the region (though this is not legally binding).

There are several notable examples of country-level approaches. For example, China has put forward Measures for Generative Artificial Intelligence, Article 4 of its Measures for Identifying Synthetic Content, which specifically requires identification of synthetic content, and Provisions on Deep Synthesis, which covers internet services and even prohibits the dissemination of “false news.” Additionally, Japan’s innovation-based Act on Artificial Intelligence-related Technologies focuses on research and development. South Korea is another country in the region that has passed comprehensive AI legislation. South Korea’s Basic Act on Artificial Intelligence adopts some ideas from the EU AI Act, though there are notable differences, especially in the realm of classifying risks — South Korea has one broad framework rather than the EU’s four categories. South Korea’s legislation also considers national competitiveness.

Neither Australia nor New Zealand have a comprehensive AI bill or law as of June 2025, but each country has voluntary frameworks, such as Australia’s Voluntary AI Safety Standard and New Zealand’s Public Service AI Framework, as well as standalone legislation regarding deepfakes either under consideration (the Deepfake Digital Harm and Exploitation Bill in New Zealand) or passed (the Deepfake Sexual Material amendment to Australia’s Criminal Code). Both countries are relying on existing law to regulate AI at the moment.

Other countries in the region are also considering legislation, including the Philippines (which is also debating a bill on AI development), Taiwan, Thailand (regarding both business operations and AI innovation) and Vietnam (examining the digital technology industry more broadly). Several others have published national frameworks including Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. And while Fiji, Laos, Mongolia and Myanmar have begun planning for AI regulation, they have not yet published official government documents. Most of the smaller island nations in this region do not have existing AI laws or AI frameworks.

Overall, the approaches in East Asia and the Pacific range from innovation-centered to harm-prevention. Few explicitly discuss journalism and the information space. Deepfake and synthetic media regulations, transparency, data privacy and mitigating algorithmic bias receive a large amount of attention, as does increasing technological capacity.

By the numbers

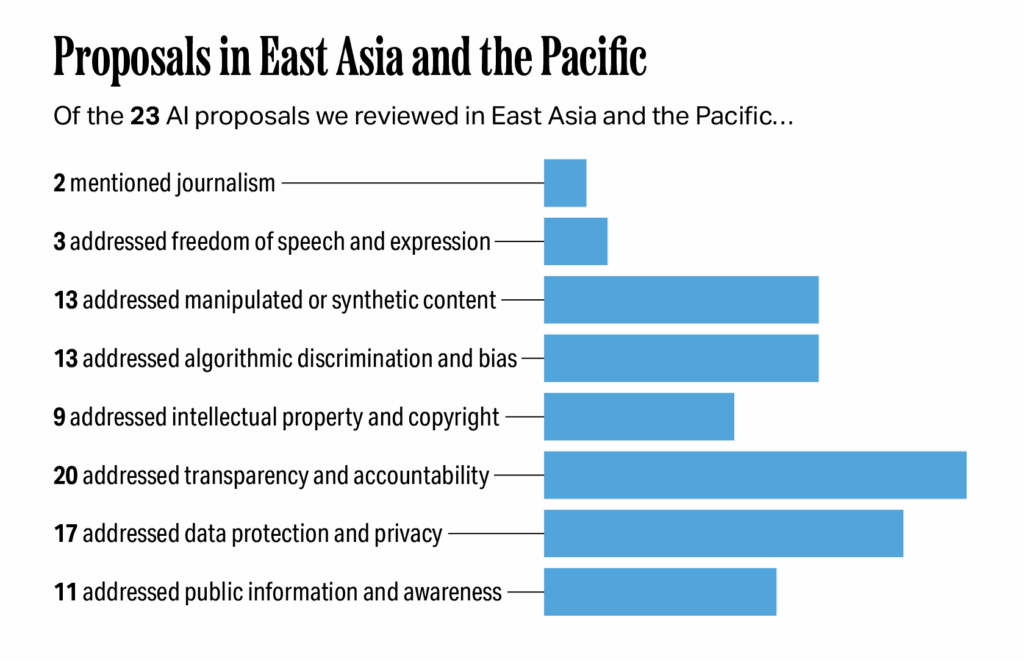

Of the 23 proposals we reviewed in East Asia and the Pacific, two specifically mentioned journalism; three addressed freedom of speech or expression; 13 addressed manipulated or synthetic content; 13 addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; nine addressed intellectual property and copyright; 20 addressed transparency and accountability; 17 addressed data protection and privacy; and 11 addressed public information and awareness.

Impacts on journalism and a vibrant digital information ecosystem

The proposals we examined across the East Asia and Pacific region have implications for journalists in each of the seven topics. Public awareness campaigns and educational programs produce opportunities for journalists to not only become more knowledgeable about AI technologies, but also to share information with the public. Many of the proposals, including those in China, South Korea and Vietnam, also explicitly address manipulated content and the transparency measures needed when disclosing to the public that AI has been used to create content. Journalists are already experienced at disclosure given their profession (e.g., disclosing when measures are taken to protect a source’s identity), but with the range of languages and cultures in the region, finding the most appropriate and understandable types of labels may present a challenge to news organizations.

There are frameworks and legislation in this region considering the implications of algorithmic bias and discrimination. Bias audits can serve as insightful resources for journalists to evaluate training data and algorithmic performance, but these proposals will also require news organizations to update their existing processes to align with legally-binding regulations.

Data privacy also receives attention in this region’s AI proposals, which will further require news organizations to align their use of AI systems with these regulations. Data privacy requirements are important for protecting personal information, but they may make it more difficult for journalists to investigate training data and for newsrooms to use AI to tailor content to subscribers.

Intellectual property and copyright is integral to news organizations, but the current patchwork of approaches in the region means that international organizations will need to pay special attention to where and when copyrighted training data are legal and where they are prohibited. This variability may also cause journalists in countries with comparatively lax laws on the topic (e.g., Japan) to experience potential advantages when developing novel journalism-specific AI tools compared to their colleagues in more restrictive countries (e.g., South Korea), though it is too early to gather firm evidence on these ideas and is an area for further research.

The topic of freedom of speech and expression is the one area in which the proposals we reviewed contained little information. Given that many countries in the region have low press freedom scores, journalists may encounter challenges reporting on AI if governments or other actors limit the amount of information available to journalists. It is also important to recognize that many of the proposals we examined in the region are non-binding frameworks. Still, future determinations about who is responsible for AI outputs, how legally-binding provisions are carried out, and what penalties exist will have wide-ranging impacts on news organizations and journalists.

Freedom of speech and expression

AI summary: Proposals in East Asia and the Pacific mention freedom of speech but often lack clear rules. Australia’s standard discusses how AI can infringe on civil liberties. The lack of clear rules in AI laws, especially in regions with lower press freedom, could make it harder for journalists to report on and use AI.

Approaches

Several countries’ approaches, including Malaysia and South Korea, mention freedom of speech or expression but lack specific provisions. The Philippines’s draft legislation about deepfakes asserts that the “State recognizes the vital role of free speech in society” but also acknowledges that freedom of expression is not absolute and “carries responsibilities.” Further explanation is not provided. Australia’s Voluntary AI Safety Standard does not call out “freedom of expression” specifically, but it has a section that states “infringements on personal civil liberties, rights …” through the use of AI systems constitute harm to individuals.

Overall, based on the set of proposals we reviewed, we did not observe freedom of speech and expression outlined in detail; therefore, we did not find concrete categories for approaches in this region.

Impacts on journalism

The policies about freedoms in East Asia and the Pacific impact journalism in numerous ways. The ambiguous language in this region lacks concrete safeguards for freedom of speech and expression — cornerstones of journalism. These rights may be addressed in other legislation and documents, but their relative absence in AI legislation suggests these ideas are unimportant, especially as most countries in the region (outside of Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan) have lower press freedom scores. Journalists and news organizations may experience greater challenges both reporting on AI and using AI in settings in which press freedoms and press independence are not strongly protected.

Manipulated or synthetic content

AI summary: Proposals to address manipulated content in East Asia and the Pacific generally prohibit certain types of AI-generated content, can require reports on false information and may mandate labels on AI-generated content to ensure transparency. These policies protect journalists from deepfakes and help them identify AI-generated content, but newsrooms will need to develop appropriate labels and disclosures to follow these laws.

Approaches

Proposals across the region consider manipulated content. They generally fit into three categories.

- Prohibiting certain types of AI-manipulated content. Several policies in East Asia and the Pacific prohibit producing (e.g., New Zealand) and/or distributing (e.g., Australia, New Zealand) specific types of manipulated content, such as non-consensual intimate or sexual deepfakes, or engaging in AI-enabled fraud (e.g., Vietnam). These types of proposals typically target the end users of AI tools, not the developers of tools that include this functionality.

- Requiring reports on “false information.” China’s deep synthesis provisions require service providers — in this case, generative AI companies that provide tools to create or edit text, video, audio or images — to “employ measures to dispel the rumors” and report the incident to the relevant government department if and when their AI technology is used to create or transmit “false information.”

- Requiring labels on AI-generated content. There are also important provisions concerning content provenance (i.e., ensuring the authenticity of content) in China, Singapore and South Korea. These countries’ approaches focus on transparency and address labeling AI-generated content. South Korea’s legislation states, for example, “AI business operators shall clearly notify or indicate to users or indicate clearly when virtual sounds, images, or videos are AI-generated, and may be difficult to distinguish from authentic ones.” Arbitration of these decisions will fall under the purview of the Minister of Science and Information and Communications Technology, and methods for disclosure, as well as exceptions, will be prescribed by Presidential Decree. Similarly, China’s regulation requires information service providers to explicitly and “implicitly” (i.e., using techniques users cannot directly observe) identify synthetic media. While China and South Korea passed legally-binding regulations, the government framework in Singapore is not legally binding. Singapore also places the responsibility on service providers and not necessarily end users.

Impacts on journalism

These policies impact journalism in a number of ways. Journalists themselves would be protected from being the subject of non-consensual intimate deepfakes. Because authentication is already central to the journalism profession, requirements to label and disclose AI generated content could help journalists more quickly identify this type of content.

In the same vein, mandated labeling and transparency provisions will also apply to newsrooms across a range of content including text, images, audio and video. Journalists already regularly disclose altering voices and faces to protect identities, so these requirements are unlikely to pose a major burden on most news organizations in these cases, though this use case is not globally viewed as best practice. That being said, appropriate labels, metadata tags and other forms of provenance/disclosure will need to be developed to comply with relevant laws. The legislative examples from the region include guidelines for how these disclosures should be made, but how audiences will interpret and understand these disclosures needs further consideration.

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

AI summary: Proposals on algorithmic discrimination and bias in East Asia and the Pacific offer general guidance, establish bias audits, prohibit discriminatory AI uses and plan for government agencies to create anti-discrimination policies. These approaches carry the potential to increase scrutiny on how newsrooms use AI for content recommendations and personalization, requiring them to develop bias prevention plans. They may also provide journalists — as well as everyone, in general— more opportunities to examine AI systems for bias.

Approaches

Many of the proposals in this region discuss algorithmic discrimination and bias. They generally fit into four broad categories.

- Offering guidance and information about safe uses. Australia’s Voluntary AI Safety Standard highlights the need for guardrails to protect against AI harms in various realms (e.g., employment and healthcare) by focusing on inclusion and fairness. Relatedly, Australia’s Guidance on Privacy and Developing and Training Generative AI Models includes information about how AI systems can produce biased and discriminatory results based on their training data. We observed similar perspectives in the Hong Kong, Malaysia and ASEAN frameworks.

- Establishing bias audits. Proposals in both Malaysia and Singapore suggest regular audits of developers’ AI systems to support responsible AI use and to mitigate AI biases and discrimination.

- Prohibiting the development and deployment of AI technologies for discriminatory purposes. China’s Measures for Generative Artificial Intelligence Services regulation requires that “[d]uring processes such as algorithm design, the selection of training data, model generation and optimization, and the provision of services, effective measures are to be employed to prevent the creation of discrimination such as by race, ethnicity, faith, nationality, region, sex, age, profession, or health.” An explicit outline of these measures is not provided in the regulation. Similarly, a foundational principle in Vietnam’s legislation is that AI systems are not to be used to discriminate.

- Stating that policies to prevent AI discrimination will be created by government agencies. Section 5b in the Philippines’ draft legislation aims at preventing algorithmic discrimination by including a Bill of Rights, though the official policies to prevent algorithmic discrimination would be specified by the Philippine Council on Artificial Intelligence if and when the legislation passes. Similarly, Taiwan’s draft proposal states that the government, through the Ministry of Digital Affairs, shall prevent algorithmic bias.

Impacts on journalism

These policies impact journalism in several ways. Policies concerning algorithmic discrimination and bias will likely increase scrutiny of how newsrooms use AI to recommend and personalize their audience’s content. For example, a content personalization system might be biased against certain kinds of users by reinforcing stereotypes or only presenting certain kinds of content. Thus, newsrooms may also be tasked with creating AI bias prevention plans for the AI systems they develop and deploy in the region if these plans do not already exist.

Auditing requirements may be beneficial for journalism since journalists could have an easier time examining AI systems and their potential for bias and discrimination.

Intellectual property and copyright

AI summary: Proposals for intellectual property and copyright related to AI are still being developed and legally decided in the region, with some proposals adhering to existing laws, others allowing copyrighted works to be used for AI training with exceptions and some requiring licenses. The range of approaches and varying stages of policy development creates challenges for news organizations, as there is confusion about who owns AI-generated content, whether they need to pay for copyrighted material to train their AI and how to deal with different laws across various countries.

Approaches

There are several examples of policies and frameworks in the region that reflect considerations for intellectual property and copyright. However, they are generally not detailed, and several proposals state that specific provisions will be developed later. They generally fit into three categories.

- Respecting and protecting existing copyright and intellectual property regulations. China’s generative AI regulation stipulates that both deployers and developers need to comply with intellectual property laws in the country. A recent lawsuit found that using copyrighted data to train AI models was legal if there was no intent to plagiarize the original work, while the legal ramifications of using copyrighted works to train AI are currently being reviewed. A separate court case in China found that images generated with AI tools can be copyrighted.

That said, current copyright and intellectual property frameworks across the region may not be equipped to handle the complexities of digital content. The Philippines’ draft law, while including a provision for intellectual property, places the authority for developing these policies in the hands of the Philippine Council on Artificial Intelligence. Malaysia’s National Guidelines on AI Governance and Ethics suggest that any intellectual property and copyright material of developers/owners should be protected.

Other examples from the region include Indonesia’s circular letter on AI ethics and Vietnam’s recently passed law on the digital technology industry. Both assert the importance of intellectual property, but neither outlines specific provisions to respect and protect intellectual property and copyright.

- Permitting copyrighted works for training AI systems. Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs released updated guidance on AI and copyright in early 2024, through which the country generally espouses that copyrighted works can be used for training, unless the copyrighted data are pirated and the AI provider knowingly used pirated data.

- Requiring licensing from copyright holders for training AI systems. Taiwan’s Intellectual Property Office has a different perspective, stating that, without prior licensing from the copyright holder, using copyrighted materials for model training violates the country’s copyright laws.

Impacts on journalism

Overall, intellectual property considerations, while present in this region, do not necessarily reflect a common understanding of what constitutes violation of intellectual property rights. Although countries in this region do have preexisting copyright approaches, it often remains unclear who owns the content AI systems generate.

These approaches impact journalism in a variety of ways. For one, ambiguity about the ownership of AI-generated content affects news organizations because their content has been used to train large language models and AI systems. Some contend training AI systems with news content is related to the idea of fair usage. Australia’s government, on the other hand, recently rejected a proposal that would have allowed technology companies to mine creative content to train their AI models, preventing the “large-scale theft of the work of Australian journalists and creatives.” It is also unclear if news organizations hold the copyright to content they may have produced with the aid of AI tools.

Whether news organizations are allowed to use copyrighted material to train their own models or need to sign licensing deals with copyright holders adds a financial constraint to news organizations. The lack of interoperability in existing copyright laws and approaches across the region may also pose problems for news organizations operating in more than one country as they develop AI models and AI-generated content. News organizations may also need to verify that third-party AI tools developed abroad do not violate their country’s intellectual property laws; however, the policies reviewed for this report address this very little.

How countries in the region will enforce intellectual property and copyright provisions, which could range from banning AI products in the country to fining or even imprisoning end users, remains to be seen. Ultimately, what data are acceptable for training and who is held responsible for AI outputs will have wide-ranging consequences for news organizations across the region by (1) shaping what data can be used for training AI models, (2) determining if licensing or other forms of compensation are required for using data and (3) setting the penalties for breaking the developing regulations.

Transparency and accountability

AI summary: Proposals in East Asia and the Pacific focus on transparency in AI use by requiring labels on AI-generated content, providing notice to users, offering non-technical explanations, developing new legal frameworks, ensuring human oversight and monitoring AI systems. These policies can assist journalists by making it easier to identify and explain AI-generated content to their audiences.

Approaches

Most of the approaches in the region discuss the importance of transparency and accountability when using AI, including frameworks in Australia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore; draft legislation in the Philippines (including draft deepfake legislation), Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam; and passed regulations in China, Japan and South Korea. They generally fit into six categories.

- Requiring labeling and disclosure for AI-generated content. Policies regarding synthetic media and deepfakes, such as China’s regulation on synthetic content and the Philippines’ Deepfake Accountability and Transparency Act, include specific requirements for disclosing AI content. China’s regulation and South Korea’s 2025 AI Act are the two proposals we reviewed that also address generated text. Many news organizations, though, already have internally developed AI disclosure policies.

- Providing notice to end users about AI systems. Approaches in South Korea and the Philippines suggest or require that users be notified in advance that they will (1) be engaging with or (2) have their data used by an AI system.

- Including non-technical explanations for the public. Several proposals include provisions to provide access to clear, comprehensive explanations about what AI systems do, how they work and what protections are in place. Australia’s framework focuses on the activities of AI developers, whereas Malaysia and Hong Kong’s frameworks focus more on deployers.

- Developing new legal frameworks. Malaysia’s framework states that the country should create a legal structure that “assigns responsibility for AI systems” and clarifies how to enforce these new provisions.

- Holding AI accountable through human oversight. New Zealand’s public service framework stresses the importance of AI being overseen by “accountable humans with appropriate authority and capability.”

- Requiring AI system monitoring and auditing. A draft approach in the Philippines calls for developers and creators of AI systems to enable monitoring and auditing to “ensure that entities deploying AI technologies are accountable for their consequences,” with specific provisions being developed by the AI Board, which will be created by the legislation. Language about the importance of auditing AI systems also appears in Malaysia’s framework.

Impacts on journalism

Policies covering transparency and accountability impact journalism in several ways. Some of these approaches mandate AI disclosure. This is an opportunity to build audience trust about the AI tools used by journalists, but it also runs the risk of decreasing trust if not done in a way that the public can understand and see the value. News organizations will also need to develop disclosures and labels that use plain language. This will likely look different across the region due to distinct languages, cultures and experiences. News organizations will likely need to revise and add to existing ethics codes and style guides to codify transparency and accountability efforts related to AI models and systems.

Transparency and accountability can benefit journalists’ reporting on emerging technologies by providing greater access to training data, model development and overall AI system performance. Bias audits serve as an important opportunity for journalists to evaluate AI systems and convey how these systems work to the public. Overall, labels and disclosures, and transparency about AI systems will help journalists identify and report on AI-generated content, and explain this content to their audiences.

Data protection and privacy

AI summary: Proposals in East Asia and the Pacific encourage companies to use personal data responsibly and anonymize data. They also strengthen existing data protection laws, give individuals control over their data and create government investigation protocols for violations. These approaches will require stricter handling of personal data by news organizations (and, in fact, all sectors), potentially leading to challenges with cross-border data security and making it harder for journalists to evaluate AI systems if training data remain inaccessible.

Approaches

There are many examples from East Asia and the Pacific regarding AI and data protection/privacy. These generally fit into five categories.

- Urging companies to use personal data fairly and responsibly. Through nonbinding frameworks, Australia and Singapore urge that personal data be used fairly and responsibly by articulating how existing personal data privacy laws apply to AI. New Zealand’s Public Service AI Framework views data privacy as “a core business requirement” for those planning to distribute and use AI systems.

- Anonymizing personal data. Vietnam’s recent digital technology law stipulates that “organizations and individuals sharing, exploiting and using digital data in the digital technology industry [which includes AI systems] are responsible for anonymization of digital data unless otherwise prescribed by law.” The legislation includes similar requirements for protecting personal data.

- Strengthening and supporting existing data protection laws. Malaysia’s framework asserts the opportunity to further develop laws in the country. These protections would involve “setting standards for obtaining informed consent, ensuring data security, and defining the permissible uses of personal information.” The AI Development and Regulation Act proposal in the Philippines stipulates that personal data must be protected in accordance with existing laws.

- Providing individuals with control over their data. Hong Kong’s framework includes data privacy as one of its 12 ethical principles, with a specific focus on individual rights over personal data. Indonesia’s circular letter takes a similar approach to Hong Kong. The Philippines’s “Right to Privacy” section of its AI Regulation Act has strict requirements for protections of personal data, including that “only data strictly necessary for the specific [AI] context is collected” and that designers, developers and deployers “shall seek permission and respect the decisions of every person regarding collection, use, access, transfer, and deletion” of their personal data.

- Creating government investigation protocols for violations. Article 16 in Japan’s recent AI law asserts there will be a government investigation when “the rights and interests of citizens have been infringed” as a result of an AI system, though who starts this review and how it is done are not specified in the legislation.

Overall, countries in the region have pre-existing personal privacy and data protection laws; the examples above highlight countries considering how developments in AI intersect with these laws. Many of the countries and territories in this region mention these previous laws in their current AI approaches — particularly those with frameworks — and issue calls to update existing laws to incorporate AI technologies.

Impacts on journalism

These approaches impact journalism in important ways. The proposals we reviewed will require stricter handling of personal (potentially audience) data when developing and deploying AI models. This requires journalists and newsrooms to develop clear protocols for how to protect and handle sensitive data when using AI tools. There may be challenges for news organizations that operate in more than one country regarding how they handle cross-border data security because not every country in the region will have the same laws and regulations.

Journalists may also experience difficulty evaluating and covering AI systems if training data and algorithms are private due to personal data security practices. Developing ways to examine AI systems, while at the same time protecting personal data, will be important for journalists.

Public information and awareness

AI summary: Proposals for public awareness about AI include formal education, public campaigns and promoting AI technologies. These approaches will increase the need for AI literacy among the public and news organizations, requiring journalists to explain AI technologies and potentially collaborate on public education initiatives.

Approaches

There are several examples across the region that speak to the idea of public information and awareness across both policy frameworks and legislation. The proposals we reviewed generally fit into four categories.

- Developing formal educational programs. Indonesia, Japan and the Philippines are focusing on formal educational programs to build AI knowledge and capacity. These education programs are intended to develop AI knowledge and capacity as well as an understanding of AI ethics. However, exactly who teaches whom about AI and how this education will unfold has not yet been specified.

- Creating public awareness campaigns. The Philippines proposes to institute “a nationwide information campaign with the Philippine Information Agency (PIA) that shall inform the public on the responsible development, application, and use of Al systems to enhance awareness among end-consumers.” Proposals from Malaysia and South Korea contain similar approaches.

- Tasking AI developers and deployers with raising awareness about AI. Hong Kong’s Ethical AI Framework emphasizes that it is important for stakeholders (presumably developers and deployers) to communicate with end-users about what risks exist in AI models and how they will address these risks. The framework also touches on “educating the public to build trust.”

- Promoting AI technologies. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan also position the government as a key player in shaping public awareness of AI and include provisions about how the government needs to promote AI technologies across education, industries and the public sector. In a similar vein, Singapore’s Governance Framework for Generative AI includes a provision about “AI for Public Good” that prioritizes access to AI technologies and responsible AI use.

Impacts on journalism

Journalism is not mentioned specifically as either an audience or vehicle for public awareness campaigns. Yet, these policies can impact journalism in a number of ways. There will be a greater demand and need for AI literacy for both the public and news organizations as AI becomes more common. Journalists will be partly responsible for explaining AI technologies and their uses to the public; thus, developing AI knowledge is critical for news organizations. Public awareness campaigns may include journalists as an audience and may provide journalists with the opportunity to learn about AI and how it can aid their work.

There will be opportunities for collaboration on public education between governments, non-governmental organizations and journalism organizations. However, given disparities in technological access and usage, regional variations will likely mean some journalists will have lower AI knowledge, leaving them less able to effectively assess and explain these technologies to the public; although, technology companies or non-governmental organizations may attempt to fill this gap with their own AI training programs. CNTI’s Global AI in Journalism Research Working Group recently found that there is a dearth of research focusing on East Asia & the Pacific.

Conclusion

Countries in East Asia and the Pacific are in various stages of AI regulation. China has had regulations on AI, synthetic media and deepfakes for several years. Other countries have recently passed legislation (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Vietnam), are actively considering AI legislation (e.g., the Philippines, Taiwan) or are relying on frameworks and existing laws (e.g., Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand). AI is an ongoing area of focus for countries in East Asia and the Pacific and developing regulations and legislation will continue at a quick pace.

While no policy or framework reviewed for this report explicitly focuses on news and journalism, the approaches will still impact those working in the industry. There are opportunities for news organizations to continue building tools for their own use and to build trust with audiences as proposals in the region address transparency, bias and manipulated content.

Five of the seven topics we examined in this report — transparency and accountability; data protection and privacy; algorithmic discrimination and bias; manipulated or synthetic content; and public information — are discussed in at least half of the reviewed policies, indicating most proposals in the region are reckoning with these ideas.

Freedom of expression, compared to the other six attributes we looked at, gets significantly less attention, which may put journalism at risk. Other shortcomings in this region include vague enforcement mechanisms and unclear guidance on how to fulfill disclosure requirements. Related to these ideas is the question of who is legally responsible for AI outputs — some of these details will be decided by councils or government bodies created by bills/legislation.

Share