TL;DR

Table of Contents

AI policy in the region

In Europe and Central Asia, AI strategies and laws reflect both harm-based and innovation-based approaches. Throughout this region, including within the EU, there are varying levels of established press freedom that will have an impact on how AI laws and policies affect journalism and freedom of expression. The most significant law, the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act, is set to be implemented by 27 member states, nine candidate states and potentially three more countries through European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and European Economic Area (EEA) agreements (Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland are considering adoption; Switzerland is not). The implementation process of this law has been fragmented, and a number of issues need clarification, such as how the AI Act will interact with other existing EU legislation. This law will affect companies far beyond the region due to the large population and market size it will cover (approximately 593.9 million people1) and the number of legal systems involved. The EU AI Act also has many extraterritoriality requirements, due to a provider or deployer outside the EU being subject to the AI Act if the AI system is used in the EU, whether or not that was the intention. The EU AI Act focuses on classifying different use cases of AI according to risk levels and establishing obligations based on these classifications. Violations of the law are met with hefty fines, as laid out in Article 99, and can range up to 35 million euros, or 7% of worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher.

As EU candidate states, Serbia and Ukraine will be required to pass their own legislation that aligns with the EU AI Act. As a consequence, these countries’ strategies are largely related to the EU AI Act; however, they have some important differences, including a greater focus on innovation and public education.

It is worth noting that in November 2025, the EU Commission proposed the Digital Omnibus Package. These documents propose multiple changes to the EU digital acquis, such as the simplification of the EU AI Act and the General Data Protection Regulation. However, because the publication of this package fell outside of our timeframe, it was not examined in this report.

The countries in the region that are not required to implement EU law take a variety of approaches, and many have yet to develop strategies or introduce legislation. The United Kingdom’s AI Opportunities Action Plan and Tajikistan’s AI legislation represent a stark divergence from the EU’s AI Act by focusing solely on supporting innovation. Other countries in the region, such as Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Kazakhstan, have a mixed approach. Switzerland plans on adapting its existing laws and taking a sector-specific approach to AI rather than focusing solely on preventing harm or fostering innovation.

By the numbers

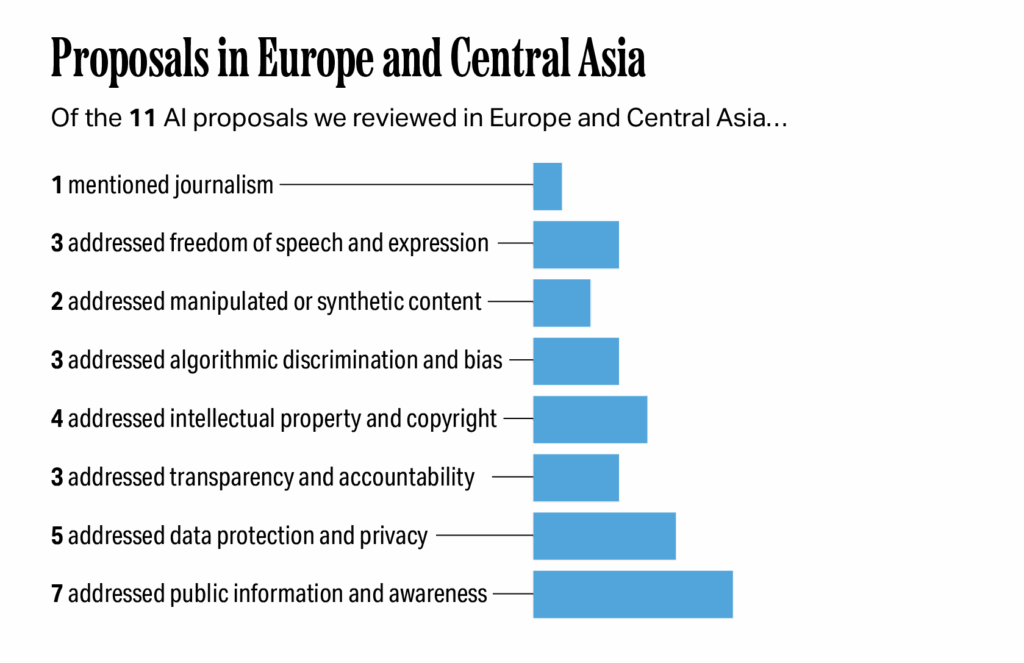

Of the 11 AI proposals we reviewed in the region, one specifically mentioned journalism; three addressed freedom of speech or expression; two addressed manipulated or synthetic content; three addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; four addressed intellectual property and copyright; three addressed transparency and accountability; four addressed data protection and privacy; and seven addressed public information and awareness.

Impacts on journalism and a vibrant digital information ecosystem

Laws regarding AI create both opportunities and challenges for journalists. Outside of the newsroom itself, transparency requirements for those developing and deploying AI make it easier for journalists to investigate the technology and the companies behind it. Furthermore, the EU’s transparency rules on generative AI allow journalists to protect their intellectual property by requesting that their copyrighted material be removed from training data. Within a newsroom, when journalists are deploying AI, whether it be for internal use or outward facing, transparency requirements can help encourage ethical practices. In addition, transparency requirements, such as labeling requirements, will impact public trust.

EU policies that do not require AI-generated text to be labeled when it has been reviewed by a human may inadvertently increase confusion because both malicious actors using AI to spread disinformation and legitimate journalists who use AI but edit the output could avoid disclosing AI use. This differs from stricter rules in Uzbekistan, where all AI-generated or manipulated content must be labelled. Under both systems, however, the level of trust between journalists and the public will likely be affected. Furthermore, the EU’s law does not explicitly ban biometric surveillance in emergencies, which could put journalists and their sources at risk. Outside of the EU, journalists face concerns over copyright since many laws and strategies provide little to no protection for their work being used to train AI models without consent.

Freedom of speech and expression

AI summary: The EU’s Digital Services Act and AI Act work together to protect freedom of expression by banning manipulative AI and requiring transparency from social media platforms, while other countries in the region mention these rights but do not have specific action plans. The AI Act has an exception allowing for biometric surveillance, which could put journalists and their sources at risk.

Approaches

Some freedom of speech and expression concerns will be addressed by the intersection of the Digital Services Act and the AI Act in the EU, especially when it comes to AI use on social media platforms. Countries outside the EU mention freedom of expression or fundamental rights without citing actionable steps.

- The overlap of the Digital Services Act (DSA) and AI Act will impact freedom of expression in the EU. The AI Act itself is not specifically designed to protect the freedom of expression, other than its bans on manipulative or exploitative AI systems that distort human behavior and impair decision-making. As stated in the Act’s preamble, the DSA and the AI Act will work together when it comes to AI systems embedded in online platforms. Algorithm recommender systems are not explicitly labeled as “high risk” under the AI Act unless they are deemed to have electoral influence. However, this concept has been critiqued for its vagueness and likelihood to include all digital platforms’ algorithmic recommender systems. Compared to the AI Act, the DSA has more stringent transparency and user control requirements. When it comes to protecting freedom of speech, the DSA has more enforceable protections than the AI Act, which has high evidentiary burdens when it comes to fundamental freedom violations. Other countries, such as Ukraine, plan to align with the AI Act when it comes to protecting fundamental rights.

- Mentioning freedom of expression without including actionable steps. Serbia’s AI strategy mentions freedom of expression, emphasizes how AI will impact the information environment as a whole and discusses potential impacts on other fundamental rights such as protection from discrimination. However, it does not have actionable steps in these areas outside of some suggestions, such as educating the public and media professionals. Countries such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Switzerland did not mention freedom of speech, expression or information but did mention fundamental rights as a whole.

Impacts on journalism

The AI Act does not mention the right to reliable information or quality journalism when discussing fundamental rights. Although democracy and access to information are typically considered to go hand in hand, the lack of specific mention in such a comprehensive law may leave fundamental rights vulnerable. The DSA, AI Act and the European Media Freedom Act overlap when it comes to moderating content news organizations share on online platforms. This overlap might have impacts on the reach of a news outlet’s content, but it is not yet clear if this will be positive or negative. News organizations’ own recommender systems on their websites would not be impacted by the DSA.

The EU AI Act also leaves open the potential for member states to implement some prohibited kinds of AI, such as biometric surveillance in cases of emergency. This exception may leave journalists and their sources vulnerable to surveillance by national authorities and the police.

Manipulated or synthetic content

AI summary: Policies throughout Europe and Central Asia have different rules for labeling AI-created content, with the EU requiring watermarks on deepfakes and Uzbekistan requiring that all manipulated content, including text, be labeled without exception. The differing rules on labeling AI-generated content can create challenges for journalism, potentially allowing false information to be shared by actors pretending to be real news sources, which could lead to a loss of public trust.

Approaches

While manipulated content is an important part of the EU AI Act and the Uzbekistan draft law, it is not addressed in other documents we reviewed. These two documents share a common approach.

- Requiring manipulated content to be watermarked and machine-readable. Article 50 of the EU AI Act requires deployers of AI systems that generate deepfakes to ensure that their outputs are watermarked in a machine-readable format. Image, audio and video content must always be labeled, with exceptions only for law enforcement purposes. In cases where an AI system generates or manipulates text intended to inform the public on matters of public interest, deployers must disclose that the content was artificially generated unless it has been subject to human review or editorial oversight. In Uzbekistan’s draft law, manipulated content must be labeled, with no exceptions, through watermarks or other machine-readable formats.

Impacts on journalism

Policies on deepfakes and other synthetic content carry significant implications for journalism. In both the EU and Uzbekistan, further clarification on the definition of AI-generated material would benefit journalists using this technology. For example, it remains unclear whether an image or video edited with AI should be classified as AI-generated content and therefore subject to labeling requirements. Generally, in the EU, AI-generated content such as images, videos, audio files and text must be labeled as such; however, if a newsroom reviews textual content and assumes editorial responsibility, labeling is not required, unless the content could mislead the public. As a result, in many cases, text generated through AI used by newsrooms will not need to be explicitly marked as AI-generated, whereas textual material not subject to review must carry a clear, machine-readable and visible label. (Malign actors posing as legitimate news sources to spread disinformation could also take advantage of the EU’s rules by claiming human review of AI-generated content, even when no such review took place.) However, AI-manipulated images, video and audio must always be watermarked and labelled as artificially generated or manipulated in a machine-readable format. These kinds of labels, however, might create confusion and short-term mistrust among audiences, according to some studies.

In contrast, Uzbekistan mandates labeling for all AI-generated content, regardless of editorial oversight, which demonstrates the importance of public understanding of manipulated content but could actually undermine trust if labeling is poorly explained or understood.

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

AI summary: Different laws across the region, especially the EU AI Act and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), are working to reduce algorithmic discrimination, while some countries like Kyrgyzstan and Switzerland mention the concern but do not offer specific actions. The use of AI by journalists for things like creating content or analyzing data will require them to be aware of and avoid biased outputs, especially when dealing with personal information about different groups.

Approaches

Algorithmic discrimination is a key concern addressed in numerous laws and strategies throughout the region, and is a major point in the EU AI Act.

- Requiring the prevention, detection, and mitigation of discriminatory outcomes on high-risk AI systems. Under the EU AI Act, developers must ensure that their training, validation and testing data meet quality criteria to help reduce bias. They can do this by adhering to Article 10(5) of the AI Act, which allows providers of high risk AI systems to process special categories of personal data under strict conditions to identify, assess and mitigate bias/discrimination, which would normally not be allowed under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- Banning some AI applications. In Article 5 of the EU AI Act, some AI applications are banned because they are seen as inherently discriminatory or carrying high risk of discrimination. These include social scoring and the use of biometric data to classify people in ways that would violate non-discrimination or equality principles.

- Clarifying the applicability of existing laws. Switzerland, for example, is clarifying how AI relates to labor laws.

- Mentioning these concerns without actionable points. Multiple countries raise concerns about algorithmic discrimination without specifying a course of action. For example, Kyrgyzstan’s law mentions the concept and considers it with the idea of data protection, but it does not present actions to address bias or discrimination.

Impacts on journalism

Throughout the region, the concept of algorithmic discrimination will be important when journalists select AI systems to use for creating content, completing administrative needs and more. The EU’s call to prevent, detect and mitigate discriminatory outcomes in high-risk AI systems has clear implications for journalism, especially for newsrooms developing or deploying AI tools for reporting, content moderation or audience analytics. This could include using AI to analyze datasets for reporting or using audience data with personally identifying or other sensitive information. Journalists using or building AI tools will need to understand these obligations and make sure they and their newsrooms comply.

Outside of the EU, the fragmented landscape will require journalists to balance the ethical use of AI with compliance across jurisdictions, and it will require them to remain aware of how bias-related safeguards may limit or shape their use of different tools.

Intellectual property and copyright

AI summary: In the EU, the AI Act and the Directive on Copyright work together to give copyright holders the ability to withhold their content from AI training, while other countries, like the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Kyrgyzstan, have less specific plans and are starting to update their existing laws. The U.K. government held a consultation in December 2024 on introducing a text and data mining (TDM) exception for AI training that will likely be similar to the EU model. The impact of these different laws is a complex legal situation where journalists’ work in countries outside the EU could be used to train AI without their permission or payment, while within the EU the opt-out system is seen as a positive step for journalism but may not be fully effective due to vague rules.

Approaches

The EU AI Act overlaps with the EU’s Directive on Copyright, a law harmonizing copyright rules across EU member states to reflect how works are created, shared and consumed online. The intersection of these two laws will drive most of the copyright protections within the EU, while other countries in the region have opted to change their existing copyright laws without offering many details.

- Giving copyright holders the ability to withhold their content from AI training. Under the EU Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, text and data mining of copyrighted materials is allowed for research purposes, but rights holders can opt out for commercial purposes, including AI model training. “General-purpose” AI models have specific transparency requirements under the AI Act, including maintaining and sharing technical documentation with downstream providers, respecting copyright law and publicly disclosing a detailed summary of training data.

- Requiring transparency about training data for generative AI. The EU AI Act’s Article 53 requires that sufficient detail about an AI system’s training data be publicly available so that copyright holders are able to opt out; however, AI companies do not have to publish their full datasets. Further details on transparency requirements have now been published by the EU in the Code of Practice for General Purpose AI, though this fell out of our research period.

- Changing existing copyright laws. In Kyrgyzstan, copyright issues are mentioned regarding the exchange of data with developers. Switzerland plans to update its existing federal copyright act, and while the United Kingdom’s action plan states that the country will “reform the U.K. text and data mining regime so that it is at least as competitive as the EU,” the U.K.’s approach to copyright issues is still being considered. However, these three AI strategies or laws do not go into specifics.

Impacts on journalism

The impacts of copyright provisions exist within a complicated and fragmented legal landscape on the issue. Not only are laws significantly different country to country, but many do not account for the digital environment nor have begun to grapple with the impacts of AI.

In the EU, the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market and the AI Act will address this issue. For journalists in the EU, the AI Act’s existing opt-out mechanism for copyrighted material has raised concerns. While the Act includes a provision allowing rights holders to opt out of having their content used for AI training, critics argue that vague implementation guidelines risk making the safeguard ineffective. On the other hand, organizations such as Reporters without Borders view the situation as a chance to push for greater transparency requirements to make it easier for authors and other rights holders to protect their intellectual property. More detailed requirements for the disclosure of generative AI systems training data were released in July 2025, including the Model Documentation Form and Public Summary Template.

Outside of the EU, copyright legislation and protections become much more complicated in the region. The strategies and legislation from outside of the EU have less of a focus on copyright, potentially posing a problem for journalists as their intellectual property could be used to train these AI systems without permission, compensation or recognition.

Transparency and accountability

AI summary: The EU AI Act has strict rules for transparency and accountability for high-risk and generative AI systems, which include requiring detailed documentation about the system and informing users when they are interacting with an AI. While some other countries in Europe and Central Asia mention the need for transparency in their proposals, they have not yet provided detailed or actionable plans. These transparency rules can help journalists investigate AI technology, allow news organizations to protect their work from being used as training data and build public trust in the use of AI in the media.

Approaches

Outside of the EU AI Act, there is limited mention of transparency and accountability for AI systems in Europe and Central Asia.

- Requiring clear user instructions in accessible language. Transparency for users of high-risk AI systems is required under the EU AI Act’s Article 13. Users must be provided with clear instructions on how to use the system, as well as clear information on system capabilities, limitations, known risks, intended purpose and necessary human oversight measures.

- Informing the public when they are interacting with an AI system. Under the EU’s AI Act Article 50, the public must be informed when they are interacting with an AI system, AI-generated content must be labeled clearly and in a machine-readable format (notwithstanding the exceptions covered under Manipulated Content) and users must know if an AI system is making decisions that impact them, especially for biometric recognition or content moderation.

- Requiring high-risk systems to provide details about training data. Systems classified as high risk under the EU’s AI Act must be transparent about their training data under Article 10. The data must be relevant, representative and as free of errors as possible. Providers must document how the data was collected and processed, and how they plan to mitigate bias or discrimination.

- Instituting audits of documentation to ensure it is accurate and up-to-date. Under the EU AI Act Article 10 and Article 11, providers are required to maintain technical documentation and record keeping of AI systems’ datasets, design, development, testing and risk management, all of which must be available to authorities for inspection.

- Emphasizing transparency as a value without actionable steps. The Uzbekistan draft law refers to a “proactive approach to transparency and ethics” but does not provide details on the approach.

- Reforming existing laws. In Switzerland the government plans to address transparency concerns through the reform of existing labor laws and sector-specific regulations.

Impacts on journalism

Transparency obligations have important implications for journalism. Broadly, increasing transparency can make it easier for reporters to investigate AI technology and the companies that provide it. Additionally, the EU’s transparency requirements for high-risk and generative AI systems will allow journalists to protect their copyrighted material by allowing them to request that material be removed from AI training data.

When it comes to newsrooms using AI, they must ensure that the systems they implement are ethically transparent and compliant with national laws. In the EU, this could involve several strict transparency requirements if the system is determined to be high risk. Additionally, if a news outlet uses AI-generated audio, photos or video, it must be disclosed as such. News outlets must also label AI-generated text unless it is subject to human review and someone takes editorial responsibility. The requirement to label AI-generated content, with exceptions for text, will likely influence the public’s level of trust in the media.

Data protection and privacy

AI summary: The EU AI Act and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) work together to address data protection and privacy concerns for AI systems, especially for personal data, while countries outside the EU, such as Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Uzbekistan, have focused on specific aspects of data protection like anonymization or alignment with global trends. These rules could require news organizations to use human oversight for AI systems that make important decisions and could make it very difficult to handle requests from people who want their personal data deleted from an AI’s training dataset when a journalist is using or deploying an AI system.

Approaches

Data protection and privacy concerns will be addressed by the EU AI Act’s overlap with the GDPR. Countries outside the EU focus on specific aspects of data privacy.

- Protecting individual rights. GDPR Article 22 provides individuals with rights against fully automated decisions that have significant impact. Additionally, under the GDPR, individuals have the right to be forgotten or have their information deleted. Due to the way data is collected and processed by AI systems, this right could be particularly hard to protect. National Data Protection Authorities and National Competent Authorities (Market Surveillance Authorities and Notifying Authorities) will work together when it comes to data protection in each member state.

Uzbekistan’s draft law imposes liability on the deployer of an AI system for the unlawful processing of personal data and plans to align with global data protection trends, including the GDPR and other major data protection laws.

- Requiring data anonymization and deletion. Such requirements are found in Kyrgyzstan’s law, which mandates data handling requirements for the design and use of AI systems. This includes requirements for the quality of training, validation and control samples. Russia’s Data Protection Law has guidelines on data anonymization that will impact the use of personal data in AI use and development by requiring additional levels of transparency.

- Deprioritizing privacy and data protection in favor of innovation. The United Kingdom’s strategy states, “Prioritisation should consider the potential economic and social value of the data, as well as public trust, national security, privacy, ethics, and data protection considerations.” This is an example of their pro-innovation approach that contrasts with the harm-based approach taken by the EU.

Impacts on journalism

GDPR’s Article 22 might require news organizations to implement human oversight for the use of AI for personalized content delivery, audience segmentation or moderation. If AI systems use personal data for training, including data from past news stories or any other source, deletion requests will become complex for the deployer, which could be the newsroom or the journalist in some circumstances, but could be an AI company that scraped news content. If the journalist is the end user of the AI system, it would be the responsibility of the AI deployer to delete the content.

Public information and awareness

AI summary: Laws in the region use various methods to teach the public about AI. Azerbaijan and Russia, for example, focus on public education programs, while Serbia focuses on training journalists, and others like Tajikistan and the United Kingdom focus on integrating AI into school curricula. The laws and strategies in the region do not currently involve journalists as key partners in public AI education, which is a missed chance to broaden the reach and impact of information about AI.

Approaches

Laws in this region take varied approaches to educating the public on AI.

- Establishing public sector education programs. Azerbaijan and Russia each have a law and strategy plan to establish education programs both within and outside of traditional education institutions. Additionally, Azerbaijan has set its sights on becoming a regional hub for AI education and plans to accomplish this by creating an AI academy for public sector education with a focus on workforce development.

- Training journalists on AI. This is a unique element in Serbia’s strategy. Serbia plans to train journalists to use AI ethically, enable greater accessibility for audiences with disabilities, and emphasize protection of freedom of expression and protection from hate speech. The country plans on organizing seminars on information security, AI and the use of big data for media professionals.

- Incorporating education about AI into secondary and higher education. Plans to incorporate education about AI into secondary and higher education are an important element of AI strategies in Tajikistan and the United Kingdom. Tajikistan’s strategy includes provisions to develop AI clubs in education centers throughout the country, implement a “Fundamentals of Artificial Intelligence” class in vocational education systems and create an AI module for senior classes of secondary education institutions.

- Educating the public on AI use in healthcare. Kyrgyzstan’s law emphasizes debunking myths around the use of AI in healthcare and demonstrating its practical implementation.

- Supporting public education without specific guidance. The EU AI Act mostly leaves it to member state discretion when it comes to increasing public education and awareness on AI. It emphasizes the importance of promoting AI literacy and encourages member states to support training and education initiatives. It also emphasizes that the AI Office and national competent authorities are encouraged to promote AI education and awareness, including by developing training materials and supporting public campaigns. Similarly, Serbia’s AI Strategy mentions education on AI and media literacy for the public; however, it does not provide specific guidance.

Impacts on journalism

On paper, Serbia’s strategy offers a strong example of including training programs to help journalists adapt to AI. However, Serbia’s media is in a position of state capture, which raises doubts about this provision’s role in facilitating a positive environment for media as Serbia integrates AI. In other countries, expanding education on AI within the public sector could further benefit the media because future journalists would gain a deeper understanding of these technologies, and media consumers would be more informed, potentially strengthening public trust in journalism.

Conclusion

As AI legislation continues to evolve across Europe and Central Asia, the successful implementation of the EU AI Act will be a crucial factor in determining the future of journalism in the AI era. This landmark law is positioned to shape the region’s approach to artificial intelligence as well as global standards, as many countries move to align their frameworks with its provisions — including countries outside the EU. As the implementation process begins, other countries in the region are expected to develop or revise their own AI strategies and legal frameworks.

One significant area of concern is how the AI Act will be enforced in countries, both within and outside the EU, that do not adhere to democratic norms. The effectiveness and integrity of its implementation in these contexts will be crucial to avoid negative impacts on fundamental rights.

Current laws and strategies in the region do not explicitly address journalism or journalists. All the same, their indirect effects will be significant on the field. This is particularly true in countries within the EU, like Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, and candidate countries such as Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where press freedom is threatened. Ongoing monitoring will ensure that AI governance does not further undermine media independence.

Share