TL;DR

Table of Contents

AI policy in the region

Representatives from 15 Latin American and Caribbean countries agreed to adopt a regional approach and roadmap to AI at a UNESCO summit in late 2024. These documents take a human-centered approach that foregrounds the importance of both multi-stakeholder governance and national sovereignty. Chile and Brazil, which lead the region in measures of AI readiness, are positioning themselves to set policy standards in their respective languages. Both have well-developed national strategies and are actively creating comprehensive legislation. Yet Brazil has long acted somewhat independently of its regional neighbors, and it remains to be seen whether other countries will follow its lead.

While the major legislative proposals in these two countries take a balanced approach — citing the EU AI Act and borrowing liberally from its risk framework, while simultaneously creating sandboxes and incentives for development — technology companies have criticized both Chile and Brazil’s proposals as excessively burdensome. Meanwhile, the national laws that have successfully been enacted to date (in El Salvador and Peru) include components focusing on both innovation and harm, primarily encourage innovation and investment, and contain relatively little detail about consequences for violations. Moreover, few countries have capacity to develop appropriate oversight mechanisms, so it is unclear how consequences would be enforced.

In Brazil, one state “leapfrogged” the national process to pass the country’s first AI law, which takes a more innovation-focused approach than the proposed federal legislation. The federal bill, first proposed in 2023, passed the Senate in January 2025 and remains under discussion in the House of Deputies. (Specific harm-based laws addressing data centers, deepfakes and online safety were also proposed in 2024, although these are at a much earlier stage in the legislative process.) A similar comprehensive law, proposed in 2024, is currently being discussed in Chile.

Five policies we reviewed in this region mention journalism or journalists, more than any other region we reviewed. Most of those mentions are brief, either stating that new AI technologies are worsening disinformation or providing carve-outs for the sector from particular policy clauses, such as consent requirements for synthetic content or strict licensing requirements for the use of copyrighted materials.

By the numbers

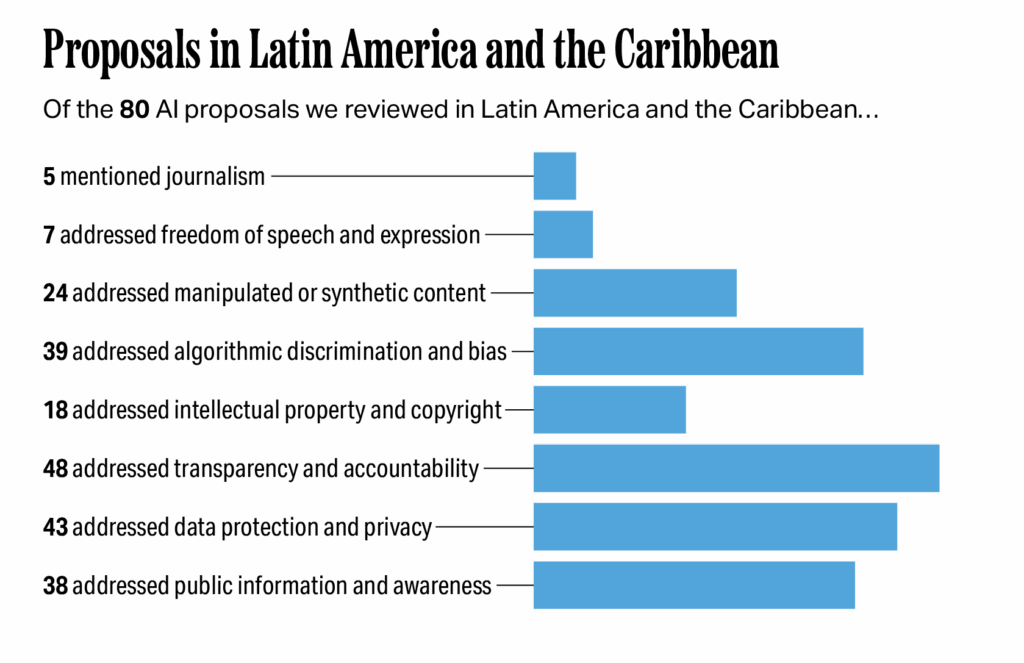

Of the 80 proposals we reviewed in Latin America and the Caribbean, five specifically mentioned journalism; seven addressed freedom of speech or expression; 24 addressed manipulated or synthetic content; 39 addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; 18 addressed intellectual property and copyright; 48 addressed transparency and accountability; 43 addressed data protection and privacy; and 38 addressed public information and awareness.

Impacts on journalism and a vibrant digital information ecosystem

Given how few laws in this discussion have been enacted to date, the impacts of AI regulation on journalism in Latin America and the Caribbean are still an open question. However, the information space appears to be more front of mind in these discussions compared to those in other regions. It is important to ensure that legislative language accomplishes its intended effect and does not raise new risks to the independence and diversity of a vibrant information ecosystem.

Ecuador’s proposed Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador (2024), one of the most comprehensive in the region, stands out for its broader vision of a vibrant and diverse digital information environment. Article 31, which focuses on “diversity and plurality in digital environments,” requires AI content recommendation systems to “expose users to a diversity of sources, topics and perspectives” and “facilitate equitable access to public-interest content from local, community and independent media.” Article 32, on “ending algorithmic censorship and manipulation,” requires additional transparency and appeals processes in this context. Still, it is not yet clear how effective these provisions will be at meeting their stated goals.

Freedom of speech and expression

AI summary: Freedom of speech is rarely included in legally binding articles of Latin American and Caribbean AI policies, with approaches focusing on banning AI systems that don’t respect these freedoms or trying to balance free speech with fighting false information. It’s unclear how these rules will affect the information environment, though they could potentially support media independence.

Approaches

Freedom of speech and expression are sometimes mentioned in the preamble or justifications of legal proposals, but they are almost never addressed in the legally binding articles of these proposals: only seven out of 80 documents we reviewed in the region addressed this topic. Moreover, about half of them simply affirm its importance without addressing it in enforceable ways.

Proposed laws that emphasize freedom of speech or expression typically address it in one of two ways.

- Banning or placing additional restrictions on AI systems that do not respect these freedoms. At least two proposals take this approach. Article 19 of Argentina’s 2024 S-Bill 2573-S-2024 bans the use of AI systems that “violate fundamental human rights” such as privacy, freedom of expression, equality or human dignity.” Similarly, Colombia’s Bill 442/2025 considers any “AI system that may affect the exercise of rights to personal privacy, freedom of expression, transparency or access to public information” to be a high-risk system. In this framework, high-risk systems are subject to higher levels of scrutiny and restriction.

- Balancing freedom of speech with the need to control disinformation. Article 32 of Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” places some limits on content recommendation algorithms in order to “minimize restrictions on freedom of expression.” These limits include clear terms, human supervision, accountability structures and appeal processes, as well as sector-wide best practices. A similar clause in Article 4 of Costa Rica’s 2023 proposed “Law for the Regulation of AI in Costa Rica” (Bill 23771) emphasizes that Costa Rica’s constitution consecrates freedom of expression, “which includes the freedom to look for, receive, and share information.” Uruguay’s 2024-2030 national AI strategy includes a similar juxtaposition.

Impacts on journalism

It is hard to predict how these proposals would impact the information environment. Restrictions on content recommendation algorithms could potentially improve the information environment created by current social media content algorithms, but they also raise questions about how the government will define “digital platforms” and “communications media.” Article 32 of Ecuador’s “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” (2024) emphasizes sector-wide standards and best practices, which could support media independence — but it will be difficult to assess its impacts without more knowledge about who will participate.

Manipulated or synthetic content

AI summary: Many Latin American and Caribbean countries are creating laws about manipulated content, mainly by requiring labels, watermarks or consent, but there is variation in who is responsible and when exceptions are allowed for journalism. These labeling and consent rules could help journalists deal with online harassment and improve information quality, but outright bans on deepfakes might create problems for journalistic work.

Approaches

Most Latin American and Caribbean countries with laws, bills or strategies have at least some mention of manipulated or synthetic content: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Perú, Uruguay and Venezuela all do — while Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador and Jamaica do not. Out of the 80 documents we reviewed, 24 addressed this issue.

Latin American and Caribbean laws, policies and proposals generally offer four approaches to synthetic and manipulated content — both as standalone proposals and as packages.

- Labeling manipulated content. Such laws differ in whether they put responsibility on software developers, users creating the content or anyone sharing manipulated content. For example, Chile’s 2023 Bill 15869-19, proposed by the Congress and later combined with Article 10 of an executive proposal, aims to regulate AI, robotics and associated technology and focuses on developers and users, requiring “developers, providers and users of AI systems that generate or manipulate image, sound or video content that noticeably resembles existing people, objects, places, entities or events” to ensure that anyone who sees the content is aware that it has been generated by AI. Article 14 of Paraguay’s 2025 “Bill that promotes the use of AI for the social and economic development of the country” says it will develop penalties (which could include fines, suspension of operations, or civil or criminal liability) for sharing manipulated content without consent, which could potentially impact people who did not themselves know that the content was manipulated.

- Requiring explicit consent from people or entities whose image is being manipulated. Brazilian Bill 5721/2023 proposed in 2023 that primarily focuses on deepfake nudity and pornography specifies in Article 3 that “the creator of inauthentic synthetic content must obtain the previous consent of persons whose images or voices will be used,” in addition to labeling. Some proposals place the responsibility on developers by forbidding the commercialization, sale, distribution and/or use of systems that have the functionality to manipulate images and audio if those systems do not include mechanisms for verifying consent. Mexico’s December 2024 Bill for National Law that Regulates the Use of Artificial Intelligence, for example, says in Article 40 that developers must revise models so that they cannot generate illegal content and notes in Article 43 that AI-generated content and images must be labeled visibly. Several countries have also passed broader laws against digital violence that include but are not limited to synthetic images, such as Mexico’s Ley Olimpia, which entered into force in 2021. (A detailed analysis of broader laws against digital violence is beyond the scope of this report.)

- Updating existing penal codes. Several laws, such as Peru’s Law 32314 (passed in April 2025), also update penal codes to clarify that existing laws about child pornography, libel or defamation also refer to AI-generated content.

- Making exceptions for journalistic uses. Some laws provide clear exceptions to consent provisions for journalism, satire, educational purposes or branding. Very few labeling provisions include exceptions. Article 36 of Argentina’s Bill 2130-D-2025, which requires consent via an amendment to the Civil Code, makes an exception for “a priority scientific, cultural, or educational reason” with precautions to avoid unnecessary harm which might include reporting on synthetic content.

- Banning the creation of deepfakes entirely. Dominican Republic Bills 495 and 563, both proposed in 2025, would make using AI to generate and spread disinformation punishable by both prison terms and fines.

Impacts on journalism

Labeling and consent requirements on synthesized audio, images and video have strong potential to support journalists in responding to online harassment. Both types of requirements — either alone or in combination — make this form of harassment more clearly illegal. These requirements also create avenues for journalists to dispute harassing content and have it removed from online portals and platforms. There remains debate over who should be legally accountable for violations: if developers are accountable, liability will rest with a smaller number of parties who are easier to identify; on the other hand, end users have more proximate responsibility for their creations.

By and large, labeling requirements on synthesized audio, images and video have potential to improve the overall information ecosystem. Legitimate journalistic uses of the technology, such as anonymizing faces in a video or reporting on deepfakes, are unlikely to be harmed by these requirements — they can simply be labeled, and often already are. Consent provisions are also unlikely to impact uses that support anonymity, since sources would presumably be informed. However, some consent provisions could make reporting more difficult, particularly if they prohibit journalists from showing manipulated content that is the subject of reporting. Explicit carve-outs may be effective. Banning deepfakes altogether may potentially have negative consequences for journalism. Legitimate uses — such as using avatars to protect journalists and sources, or including a brief clip to debunk a political deepfake — could also fall under the bans and potentially make journalists and their sources less safe.

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

AI summary: Latin American and Caribbean countries are addressing algorithmic bias with a human rights-centered approach — such as prohibiting high-risk systems, mandating audits and diverse training data, and strengthening end-user rights. This approach presents opportunities to hold AI developers and deployers accountable.

Approaches

Every single country in the region with a law, bill or strategy includes at least one reference to algorithmic discrimination and bias. Across countries, non-discrimination and bias prevention show up as broad principles for AI laws and frameworks. Every country has at least one document that mentions this topic; 39 out of 80 documents address this topic.

Not all 39 documents that make reference to algorithmic discrimination and bias address it in a meaningful way. Those that do use a number of different approaches.

- Banning AI for uses where the likelihood of bias and its impacts are both high. Proposals in Argentina in 2024, Bolivia in 2025, Brazil in 2023, Chile in 2023, Costa Rica in 2024, Ecuador in 2024 and Paraguay in 2025 include a risk classification system most likely borrowed or adapted from the EU AI Act, which prohibits most forms of biometric surveillance and social credit systems, among other uses.

- Ensuring representation earlier in the development process. These include proposals to encourage more diversity among working teams. Chile’s 2025 Decree 12 requires more representative training data. Venezuela’s 2025 AI Bill and the 2024-2028 Brazilian AI Plan incentivize better language models. It is unclear how these proposals would be enforced, although they sometimes exist in combination with auditing requirements.

- Mandating auditing and public registries. A number of proposals would make participation in periodic bias audits a requirement for doing business in their country, with penalties for unsatisfactory results ranging from warnings to large fines to potential loss of business licenses. For example, Article 17 in Paraguay’s 2025 proposed “Bill that promotes the use of AI for the social and economic development of the country” would create a national registry of AI systems, prohibit the use of biased or insufficient data, require traceability and explainability mechanisms and implement regular auditing. Organizations that fail their audit will be required to create a remediation plan and may be subject to additional fines and punishments. Some proposals, such as Article 29 in Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador,” further highlight the need to mitigate bias against specified historically marginalized groups.

- Updating existing laws about personal data and discrimination. Several countries are updating existing laws to clarify who is legally responsible for discriminatory AI and requiring AI tools to comply with these laws. Most of these laws hold both the developer and the deployer accountable. In this vein, Argentina’s 2025 proposed 2130-D-2025 would add considerable text to the country’s Personal Data Protection Act by specifying who is responsible for violations of data policy and outlining rights for anyone impacted by discriminatory automated decisions.

- Strengthening end-user rights. Another relatively common proposal enshrines end-user rights into law, including the right to human review and human decision-making. That is, many laws guarantee that people can appeal algorithmic decisions and request that a human review the decision. Article 51 of the 2025 Bill 495 from the Dominican Republic, for example, grants the right to appeal to anyone affected by decisions made partially or fully by an AI system, as long as one of the following conditions is met: the decision violates fundamental rights, includes discriminatory bias, creates harm in any area regulated by the state, lacks sufficient transparency or greatly harms the user. If this type of law is not accompanied by larger-scale auditing, problems would primarily come to light when individuals report impacts and seek human review. That could mean that the responsibility for correcting discrimination would lie primarily with the people who are impacted by it.

- Ensuring diverse outputs of recommendation algorithms. In addition to clauses about algorithmic bias more broadly, Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” also includes two articles addressing “diversity and plurality in digital environments” and “algorithmic censorship and manipulation.” Article 31 requires providers of content recommendation algorithms to ensure that users see diverse sources and perspectives, including “public-interest content from local, community and independent media.” Article 32 specifies that these platforms must have human supervision, traceability mechanisms and an appeals process if content is removed or has limited visibility.

Impacts on journalism

Most of the legal proposals addressing algorithmic bias in Latin America and the Caribbean are primarily concerned with decision-making algorithms and are unlikely to apply directly to journalistic uses of AI.

Articles 31 and 32 of Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador,” which focus on content recommendation, are the primary exception. Article 31 requires algorithms to provide diverse sources. Doing so could potentially improve the information environment created by current social media content algorithms, as well as raise the visibility of journalistic content online. However, until it is operationalized, there remain questions of how it could negatively impact journalism. Article 31, as currently written, may require producers of journalism to include “a diversity of sources” — not just the platform and search companies. If so, producers of journalism may be unable to use recommendation or prioritization algorithms on their own apps or platforms because they are restricted from offering content exclusively from their own outlet or organization. Moreover, it is unclear who will assess the “diversity of sources, topics and perspectives” or determine what counts as “public-interest content.” Without clarity, these terms could potentially be weaponized against content producers. Article 32, which restricts the use of content recommendation algorithms and requires human supervision and appeal mechanisms, explicitly applies to “communications media.” Even once these definitional questions are clarified, Ecuador may not have the leverage to enforce these laws on multinational social media platforms. Most likely, these companies would either pull out of Ecuador or refuse to comply, as they have done in the face of regulation elsewhere.

Provisions in other policies might also apply to recommendation, personalization or content-delivery algorithms. In these cases, algorithms may require additional scrutiny or transparency from news organizations, but they do not seem likely to foreclose legitimate journalistic uses.

In addition, the role of registries and audits may present an opportunity for journalism to report on the accountability of AI developers and implementers. In general, so-called “sunshine laws” that promote transparency in particular sectors have helped journalists access information.

Intellectual property and copyright

AI summary: Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are taking varied approaches to intellectual property for AI, focusing on the rights of copyright holders if their work is used to train AI systems, the intellectual property of developers and/or ownership of AI-generated works. These rules could help news organizations financially by making AI developers pay for copyrighted content, but it’s important to have exceptions for journalistic uses of AI, especially since laws that punish end-users could put journalists at risk.

Approaches

Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean rely on intellectual property law to protect Indigenous and traditional arts from appropriation and theft. This salience may be why intellectual property and copyright come up across most countries with AI laws, strategies, or proposals in the region; the exceptions without such provisions are Bolivia, Paraguay and Venezuela. Because each country has a somewhat different intellectual property regime, it is challenging to summarize comprehensively. For example, Colombia has collective management of copyright, with several large organizations empowered to administer rights on behalf of creators. Out of the 80 documents we reviewed, 18 address this concern.

Proposals in Latin America and the Caribbean include six approaches.

- Participating in international regulation and standards. Chile’s Decree 12, updating their national AI policy as of January 2025, recommends “participating in international dialogues and decision-making about regulating AI in relation with intellectual property, contributing to the formation of global policies.”

- Requiring prior authorization to use copyrighted work to train AI models. A number of proposals emphasize protecting existing copyrights, often through a combination of authorization, licensing and transparency mechanisms. For example, Article 6 of Costa Rica’s proposed “Law for the Implementation of AI Systems” (Bill 24484/2024, one of three bills under discussion) includes “the use of content protected by copyright and associated rights, which in all cases will be subject to the previous authorization of the corresponding rights-holders” as an area of primary impact of new AI technology, and thus subject to state evaluation and authorization. Article 13 of the same law explicitly prohibits unauthorized use of copyrighted materials, and Article 14 imposes a transparency requirement about the use of copyrighted materials. Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” protects materials in the public domain from claims of copyright if an AI re-generates them. Colombia, Mexico and Panama have similar provisions in bills currently under discussion.

- Including exceptions for fields like research and journalism. Some laws contain provisions that exempt the use of copyrighted materials for scientific or journalism purposes. For example, the comprehensive law currently under discussion in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, Article 42 of Bill 2338/2023, includes this provision: “The automated use of works, such as extraction, reproduction, storage and transformation in processes of data or text mining in AI systems, does not constitute a copyright offense in activities undertaken by organizations and institutions of research, of journalism, or by museums, archives, or libraries, as long as … 1. Its objective is not the simple reproduction, exhibition, or dissemination of the original work; 2. The use is in the necessary amount for the goal to be reached; 3. It does not unjustly prejudice the economic interest of the title-holders, and; 4. It does not interfere with the normal use of the works.” This type of provision would make it allowable to use AI to recognize patterns in published books (without author consent), but not to train commercial generative AI on those same books.

- Requiring traceability of sources or disclosure. Often in combination with prior authorization and licensing requirements, some proposals require text generation to be clearly traceable by including cited sources. Panama’s 2024 proposed “law which establishes a legal framework, promotion and development of AI in the Republic of Panama,” which is being discussed, lays out the need for traceability in a discussion of guiding principles in Article 13 and is explicit that the use of AI does not exempt anyone from responsibility if they have violated someone else’s intellectual property in Article 9.

- Explicitly protecting AI models, datasets and algorithms as intellectual property. To support innovation, a number of provisions focus on the intellectual property of model developers and creators. A proposed Colombian law presented to the Congress in May 2025, includes a provision that the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation will provide legal and technical assistance so that AI researchers and developers can take advantage of patent and copyright protection. The 2025 Argentinian Bill 0511-S-2025 would require government agencies to prioritize the intellectual property of the companies it regulates. Proposed Dominican and Salvadoran laws also emphasize the intellectual property rights of developers.

- Clarifying the copyright status of AI-generated works. Who owns work that is partially or wholly generated by AI is not uniformly agreed upon throughout the region. One provision offers potential solutions: Ecuador’s 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” says that work generated with help from AI can be copyrighted by its human author in Article 34, while Article 35 says work generated fully autonomously by AI goes directly to the public domain. Mexico also has a 2025 proposal addressing the copyright status of AI-generated work in which the law details a category of “significant human interaction” that creates works protected by copyright, while works created without it belong to the public domain.

- Updating existing laws. A few proposals attempt to address these issues by updating existing copyright laws, but many of them (such as Peru’s Law 32314, passed in April 2025) lack specificity.

Impacts on journalism

The implications for journalism are particularly difficult to tease out given the many complexities of extant copyright law and its overall inadequacy for the digital information ecosystem. None of these proposals are specific about how to assess the value of digital content. That said, international cooperation and regulation could go a long way towards simplifying the current patchwork of intellectual property regulation, especially if there is diverse representation from this region.

On the whole, requiring developers to license and pay for copyrighted content they use to train their models is likely to benefit news organizations financially. Exemptions for journalistic uses of AI tools are also an important safeguard, especially in countries where laws penalize end-users, which means that journalism organizations may be at risk of inadvertent violations if they use third-party tools. That said, carve-outs will then need to specify who and what qualifies for them.

Transparency and accountability

AI summary: AI policies in the Latin American and Caribbean region are guided by the principles of transparency and accountability, but not all proposals operationalize them; those that do include mandatory disclosure of AI interactions, a right to human review, requirements for accessible language in documentation and the creation of public registries. In some cases, it remains unclear whether the burden of compliance will fall on developers or the organizations that deploy the technology, and some rules might place a heavy burden on news organizations.

Approaches

Algorithmic transparency and accountability come up in laws and legislative proposals across Latin America and the Caribbean as overarching principles of AI governance and regulation. In fact, every country with at least one bill, law or strategy referenced this policy component. It was also the most commonly addressed topic in the region, appearing in 48 of the 80 documents we reviewed.

In this region, there are six main approaches to address transparency and accountability.

- Requiring that users must know that they are interacting with an AI system. Such provisions range from requiring watermarking or labeling on AI-generated content to requiring labeling on all algorithmic systems and tools. The latter would require apps and platforms (including social media, search engines and streaming sites) to spell out that content is recommended algorithmically. It could also mean that companies have to label algorithmic processing of data (e.g. job applications, access to financial products) more clearly. In some cases, such as Chile’s Bill to regulate AI, robotics and associated technology (Bill 15869-19, proposed by the Congress in 2023 and later combined with an executive proposal), the mechanisms disclosing AI interaction are not specified.

- Requiring full traceability and auditability of decisions. These proposals, which go further than the first category, require all decisions made by an AI system to be explainable and understandable. In frameworks that categorize AI systems by level of risk, these requirements are often proposed only for high-risk AI uses. Chile’s proposed 2024 “Artificial Intelligence Law” (Bill 16821-19) says in Article 8 that high-risk systems “will be designed and developed with a sufficient level of transparency so that their users and recipients reasonably understand how the system works, in accordance with its intended purpose.” This provision also says that when high-risk systems come on the market, they will be required to use state-of-the-art technical means for interpretability.

- Creating a right to human review. Many legal proposals, particularly those that focus on auditability or explainability of an AI system’s decisions, further enshrine the right to human review. “AI Bill of Rights” provisions, such as Articles 5-12 of Paraguay’s 2025 Bill that regulates and promotes the creation, development, innovation and and implementation of artificial intelligence systems, regularly include a right to challenge algorithmic decisions, a right to opt out of AI decisions altogether and a right to request human review of any decision. However, the Paraguayan bill does not lay out specific processes for requesting this review, nor does it identify who would conduct it.

- Reporting requirements and creating public logs and records. Many proposals require developers and providers to register requests for things like licenses and problems like failed audits with the relevant government agency. In many cases, reporting requirements are associated with the creation of public records, so that the information is made fully transparent to the public. For example, Chile’s Bill to regulate AI, robotics and associated technology (Bill 15869-19, proposed by the Congress in 2023 and later combined with an executive proposal) says, “The commission must have a public registry of: [1] The requests for authorization for development, distribution, commercialization or use of AI systems, signaling explicitly if they were authorized or rejected by the Commission. [2] The serious incidents and defective functioning reported by developers, providers and users as well as the judgment that Commission has adopted.”

- Requiring documentation to be in plain, accessible language. Another fairly common transparency provision is ensuring that developers and providers offer documentation, and requiring that it be usable and accessible. For example, Article 31 (Transparency and Explainability in the use of Information) of Costa Rica’s 2023 Law for the Responsible Promotion of AI (Bill 23919) reads in part, “The information that providers offer in terms of sale of goods and services should be offered in digital, audio, and photographic format and the information should be concise, complete, correct, clear, pertinent, accessible and understandable for users, according to the right to public information.” The provisions we reviewed do not specify which languages must be provided. This is important since hundreds of languages are spoken in Latin America and the Caribbean, and access to materials is far from guaranteed for speakers of most of them.

- Requiring AI to cite sources. Mexico’s 2024 Bill for National Law that Regulates the Use of Artificial Intelligence would require AI models to cite their sources of information, but there are no specifications.

Impacts on journalism

Requirements that people must know they are interacting with AI systems could be complicated to implement, depending on how “interacting” is interpreted. For example, many journalism producers use algorithms that personalize or filter content, and it’s not clear how best to label such tools. Similarly, if a journalist uses AI tools to transcribe interview audio and then writes a story that quotes from those interviews, would a reader be “interacting” with an AI system?

Laws requiring accessible documentation could make it easier for journalists (who may not have technical expertise) to report on new technologies and to select appropriate tools for professional use. In general, so-called “sunshine laws” that promote transparency in particular sectors have been important to journalists’ ability to access information, and AI is no exception. Accessible documentation could also make it easier for the general public to be better informed about the technology, as research shows that people almost never read terms and conditions because they are too technical.

Some proposed laws focus more on the transparency obligations of deployers rather than developers, which could place a heavy burden on journalism producers.

The Mexican proposal that requires AI to cite its sources will impact journalism, but it is difficult to predict how. This proposal is not compatible with current LLMs, which frequently cite sources that do not support, or even contradict, their results. Such a law could theoretically drive the development of entirely new models, but some experts worry that the proposal is unenforceable because it lacks an understanding of current capabilities of the technology it seeks to regulate. Citing sources with links might potentially drive more traffic to news sites, which would be beneficial, but some research has found that users click on links from AI outputs infrequently.

Data protection and privacy

AI summary: Latin American and Caribbean countries are making data protection and privacy a key guiding principle of their AI policies by banning indiscriminate surveillance; enforcing existing privacy laws; and requiring data minimization, informed consent and periodic reporting. While banning AI for surveillance might make journalists and their sources safer, this benefit is limited by exceptions for government use.

Approaches

Most countries in the region, but not all, have data privacy laws in place that would likely apply to AI, although a detailed examination of these laws is out of scope of this report. Across countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, data protection and privacy are regularly mentioned as key guiding principles in AI regulation. They appear at least once in a document from every country whose bills, strategies or laws we considered. More than half of the documents we reviewed — 43 out of 80 — addressed data protection and privacy.

These principles are operationalized very differently from one place to another, even within this region.

- Banning indiscriminate data collection and/or surveillance. A number of proposals spell out explicitly that certain practices on data collection and/or surveillance are forbidden. For example, Article 15 in Paraguay’s 2025 “Bill that promotes AI for the social and economic development of the country” says, “The use of AI is prohibited for indiscriminate surveillance, unauthorized monitoring of private life and massive collection of personal data without the explicit consent of the person or without a duly justified judicial order.” Another common proposal is to ban real-time biometric identification, following the EU AI Act. Such proposals do not often apply to government agencies.

- Highlighting the relevance of existing data privacy protections and frameworks. A number of countries, such as Brazil, have extensive existing data privacy protections that are similar in scope to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (and, in some cases, modeled on it). In these contexts, many laws simply include a provision that all privacy protections will be enforced. Brazil’s 2024 proposed Bill on the Regulation of AI Data Centers (Bill 3018/2024) effectively repeats a number of requirements from their data protection law in Article 4: “The operators of data centers must (1) establish clear data governance policies, encompassing collection, storage, processing, sharing and elimination; (2) designate a Data Protection Representative in accordance with the General Data Protection Law (LGPD); (3) conduct impact evaluations on the protection of personal data periodically and any time there are major changes in the processes or technologies used; (4) implement programs of ongoing training for staff on information security and data privacy, with periodic mandatory refresher courses; (5) assure that sensitive data are treated with the highest level of security and confidentiality.”

- Minimizing and anonymizing data use. Many provisions call for limiting the use of data wherever possible, and to anonymize and pseudonymize data to minimize the risks of data breaches. For example, Article 23 (“Privacy since Design and by Default”) of Ecuador’s proposed 2024 “Organic Law for the Regulation and Promotion of AI in Ecuador” reads, in part: “AI systems will be configured such that, by default, data will not be accessible to an indeterminate number of people without the intervention of the individual. Techniques will be used to minimize, anonymize, pseudonymize, or encrypt data from collection, transmission and storage …”

- Informed consent and the right to data correction and/or removal. Another commonly used provision requires informed consent for data use, and includes rights to correction and/or removal of personal data from databases, including the datasets used to train various AI tools. For an example, see Articles 13, 16 and 17 of Peru’s 2024 proposed “Law for promotion and regulation of AI in Peru” (Bill 8223/2023).

- Monitoring and impact reports. To ensure that privacy obligations are taken seriously, many proposals require periodic monitoring, evaluation and reporting on data privacy. A proposed Colombian law, presented to the Congress in May 2025, would empower the Superintendency of Ministry and Commerce to audit, investigate and take preventive measures to protect data privacy.

- Data sovereignty through infrastructure. While the laws and proposed laws we reviewed did not typically focus on these concerns, national strategies often highlighted the need for infrastructure to guarantee not just data privacy but data sovereignty. For example, the Brazilian Artificial Intelligence Plan (PBIA) 2024-2028 calls for a global Portuguese language model that can support data sovereignty, as well as a robust public data ecosystem in the sovereign cloud.

Impacts on journalism

Banning AI for surveillance is likely to make journalists and their sources safer, although most such provisions have exceptions for government uses. Given that government surveillance of journalists is already widespread in this region — and that state actors are the biggest threat to journalism in Latin America and the Caribbean — these laws may not impact one of the primary safety concerns journalists face.

Bringing privacy expectations and requirements in line with larger national and international frameworks has the benefit of consistency and could simplify compliance. Many countries have existing national privacy regulations that naturally will impact AI, but reviewing them in detail fell outside the scope of this report.

Public information and awareness

AI Summary: Many Latin American and Caribbean countries are promoting public awareness about AI through government-led initiatives or by holding developers responsible for public education. Broad educational efforts about AI would likely help society, but the implications for news organizations are unclear.

Approaches

Many countries (including, at a minimum, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Jamaica, Panama, Paraguay, Perú, Uruguay and Venezuela) have laws, bills or policies that include provisions to promote public awareness about AI. Out of the 80 documents we reviewed, 38 addressed this issue.

In general, Latin American and Caribbean policy proposals take one of three approaches to educating the broader public about AI.

- Providing government-led education. A government agency, often a newly created AI authority, is held responsible for public literacy and education. For example, Venezuela’s 2025 AI Bill charges the Ministries of Education and University Education in Article 33 with incorporating content about AI into “all levels and modalities of the educational system.” Article 34 assigns these ministries as well as the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation with developing training and upskilling programs. In addition, Article 35 says “the State” will provide digital education in AI for the general population.

- Holding developers and deployers of AI tools responsible for public literacy and education. For example, Article 18 of Argentina’s Bill S-2573-S-2025 (proposed in 2024, one of many competing proposals) specifies that “those who are subject to this law must provide clear, understandable and accessible information about responsible use of AI systems, including limitations, risks and necessary precautions. They must promote education and training in responsible use of AI, and promote awareness of associated risks and best practices to avoid errors and minimize potential harms.” Article 2 defines subjects of this law as “any human or legal, public or private person, who develops, researches, implements, commercializes, offers, distributes, imports or uses AI systems in Argentinian territory,” regardless of the location of the server or company.

- Requiring educational campaigns without specifying who is responsible. For example, Article 17 of Costa Rica’s proposed 2023 “Law for the Regulation of AI in Costa Rica” (one of three bills under discussion) reads simply: “Training and awareness-raising about human rights in the context of AI will be promoted. Training professionals in ethics and human rights in the AI context will be encouraged.”

Impacts on journalism

Widespread educational and workforce development campaigns are likely to benefit societies as a whole. They may also benefit journalism if increasing numbers of journalists are able to participate. Trust in business far outpaces trust in government across Latin America, suggesting that developers and deployers may be important messengers in this context. Government-created educational content may decrease reliance on educational content published by developers, who have a clear conflict of interest, but it is unclear whether most people would trust government content.

While none of the documents we reviewed provides an explicit role for journalism, the ubiquity of proposals for public awareness and literacy campaigns may still have positive implications for the field. Journalists continue to play an important role in explaining new technologies to the public, so journalist access to this information would be of value to technology companies. It is also important that journalists themselves have deep and on-going knowledge about the various facets of AI and technology broadly, as well as access to a wide pool of sources, to cover the material thoroughly and accurately. Unfortunately, there remain gaps in access to information in Spanish and Portuguese, the most widely spoken languages in the region — and the gaps are far wider for the hundreds of Indigenous languages that are not yet meaningfully supported in AI tools.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen whether Latin American and Caribbean countries will succeed in taking a coordinated regional approach to AI regulation. Currently, the countries positioned to be regional leaders — Chile and Brazil — are debating comprehensive legislation that balances incentives for innovation with meaningful regulation designed to protect against harms. These balanced approaches are being debated with a backdrop of global tension, most recently between the BRICS bloc’s explicit commitment to global AI governance and the U.S.’s push for global deregulation.

Across countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, proposed AI laws address the full range of issues we considered, and they often explore impacts on the information space. It will remain crucial to ensure that policy language in the region safeguards media independence, a plurality of fact-based information sources and a vibrant digital news ecosystem.

Share