TL;DR

Table of Contents

AI policy in the region

AI regulation in the Middle East and North Africa is largely at the nascent stage. AI readiness varies widely across the region, with the United Arab Emirates ranking 13th in the world for AI readiness, while Yemen comes in last place in the world, according to Oxford Insights’ 2024 Government AI Readiness Index.

AI Readiness of States in the Middle East and North Africa

| Country | Global Rank (out of 188) |

| United Arab Emirates | 13 |

| Saudi Arabia | 22 |

| Qatar | 32 |

| Oman | 45 |

| Jordan | 49 |

| Egypt | 65 |

| Bahrain | 68 |

| Kuwit | 77 |

| Lebanon | 82 |

| Tunisia | 92 |

| Morocco | 101 |

| Muritania | 105 |

| Iraq | 107 |

| Algeria | 115 |

| Palestine | 125 |

| Libya | 149 |

| Sudan | 176 |

| Syria | 186 |

| Yemen | 188 |

Already, though, several countries have developed national AI strategies or policies, which set standards for the role of AI across sectors. These strategies take a mix of innovation-based and harm-based approaches, demonstrating that AI is not always viewed the same way across the region. Regardless, countries in the region have found common ground on AI, with the Gulf Cooperation Council (of which Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are members) endorsing the Bahrain-drafted Guiding Manual on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence Use. Some North African countries have also highlighted their intention to embrace the African Union’s Continental AI Strategy and to cooperate with other countries on the continent.

While countries have derived different definitions of AI — when one is included in these proposals at all — most associate AI with the “simulation of human intelligence.” Libya’s National AI Policy, for example, notes that “Artificial intelligence is a branch of computer science that simulates human cognitive abilities through intelligent machines,” while Qatar’s Guidelines for Secure Adoption and Usage of Artificial Intelligence state that AI is “is designed to carry out any tasks associated with human intelligence, in a manner that mimics the human mind with a certain level of autonomy.” Policies in Oman, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) similarly define AI as attempting to perform functions that are generally associated with human cognitive abilities. This language highlights that AI is not omnipotent; it attempts to mimic the outputs of the human brain, but it ultimately does not work the same way as human reasoning and cannot be expected to mimic the human mind without fail. As such, many countries include requirements for human oversight over AI systems in their strategies, meaning that humans should review these technologies and make the final decisions, instead of relying on AI to tell humans what to do on any given topic. This is especially important for journalists: Because AI is fallible, and because good reporting must be based on verifiable facts, journalists should never rely solely on AI technology. Likewise, they should fact-check any AI-generated information they receive from sources.

As of June 2025, two pieces of AI legislation have been passed in the region: the government of Abu Dhabi’s Law No. 3 of 2024, which established the Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Technology Council (AIATC) to regulate projects, investments and research related to artificial intelligence and advanced technology in the emirate of Abu Dhabi; and Qatar’s AI Guideline to Regulate the Use of AI by Qatar Central Bank Licensed Entities, which regulates the use of AI in the country’s financial sector. Neither of these laws have clear implications for journalism yet; although, because the AIATAC is charged with guiding policies and strategies for AI in Abu Dhabi, it is possible that its future rulings will impact journalism. The governments of Bahrain and Egypt are developing comprehensive AI laws that will impact journalism when entered into force — Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law was unanimously approved by the Shura Council in 2024 and is awaiting parliament’s approval, and Egypt is reportedly in the final stages of developing a set of laws to regulate AI and dataflows.

By the numbers

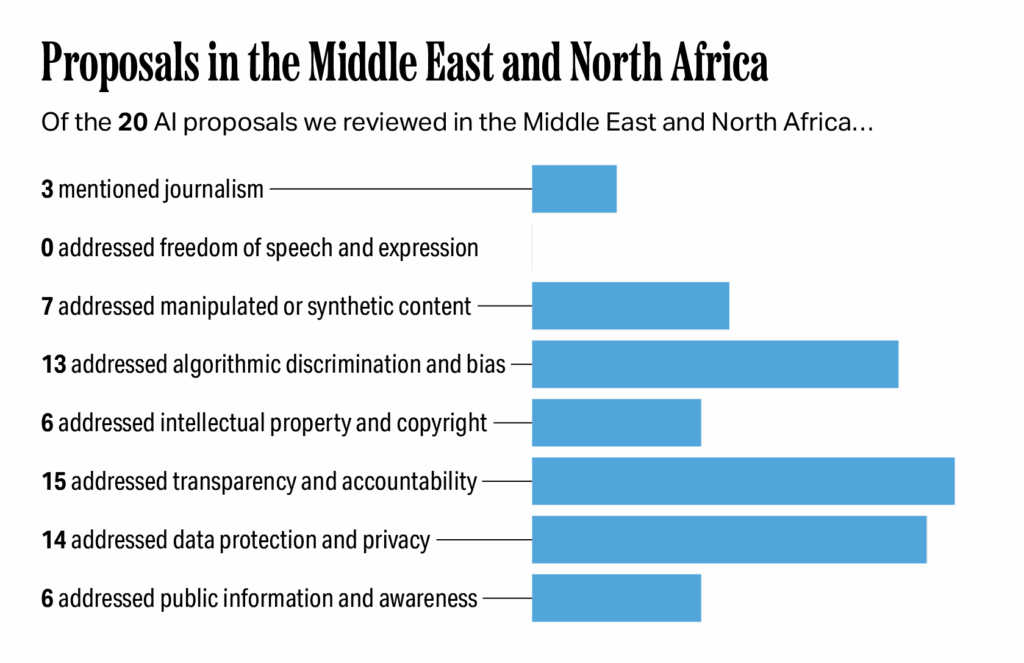

Of the 19 AI proposals we reviewed in the region, two specifically mentioned journalism; none addressed freedom of speech or expression; seven addressed manipulated or synthetic content; 13 addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; six addressed intellectual property and copyright; 15 addressed transparency and accountability; 14 addressed data protection and privacy; and six addressed public information and awareness.

Impacts on journalism and a vibrant digital information ecosystem

Each of these seven policy areas has the potential to significantly impact journalism and the information space across the region. AI awareness, literacy and education campaigns could provide journalists with the knowledge they need to cover AI, but journalists will have to ensure their coverage remains independent. Attempts to counter some of the risks associated with AI-manipulated content could help prevent online violence against journalists, but vague wording in these laws could also be used to penalize journalists for reporting on or using AI. Journalists and newsrooms will have to strike a balance between using AI to personalize content and ensuring their AI tools avoid algorithmic discrimination and bias. Some proposals on intellectual property and copyright would benefit journalists by requiring AI companies to remunerate them for the use of their content. Transparency efforts are generally beneficial for journalism, as they can improve journalists’ understanding of how AI technology is being used and how it is arriving at its conclusions, thus enabling journalists to better report on the technology and the entities using it. Journalists and new organizations will be required to build data protection and privacy into their AI systems, which could protect journalists and their sources. Proposals that prohibit the use of AI for surveillance would also be a boon to journalists in the region. Finally, the lack of inclusion of freedom of speech and expression in the reviewed AI policies mirrors the lack of press freedom that journalists experience in the region.

Freedom of speech and expression

AI summary: AI proposals in the Middle East and North Africa do not mention freedom of speech or expression, reflecting the region’s overall low ranking in press freedom and the ongoing threats journalists face.

Approaches

None of the reviewed policies, strategies or laws specifically mention freedom of speech or expression.

Impacts on journalism

The lack of inclusion of freedom of speech and expression in the reviewed AI policies does not necessarily signify that countries in the Middle East and North Africa do or do not support this right. In fact, with the exception of Morocco, the North African countries covered in this section could choose to follow the African Commission’s 2019 Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa. The Declaration is not enforceable, but it does establish a normative framework that member states of the African Union should seek to uphold.

Nonetheless, according to Article 19’s 2025 Global Expression Report, the Middle East and North Africa has the lowest expression score of any region, with not a single country ranking as “open.” There is a close connection between freedom of speech and expression and freedom of the press — freedom of speech creates the environment in which freedom of press can exist. The lack of consideration for freedom of speech paired with the low rankings across the region may signify a negative environment for press conditions. Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 World Press Freedom Index reinforces this. According to the index, the existence of the free press in the Middle East and North Africa continues to be hampered by violence, repressive legal systems and political control, even though freedom of expression is constitutionally enshrined in some countries, such as Jordan and Israel.

Manipulated or synthetic content

AI summary: Proposals from several countries in the Middle East and North Africa aim to address the risks of AI-generated disinformation by prohibiting certain uses of AI, setting standards for AI development, or using AI to help detect false content. While these efforts could help protect journalists from manipulated content and improve the quality of the information space, some of the vague rules might lead journalists to censor themselves.

Approaches

Several proposals throughout the region note that AI can exacerbate the risk of mis- and disinformation, including through the generation of deepfakes, but only a few lay out strategies for addressing manipulated content.

- Prohibiting some uses of AI. Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law strictly prohibits the use of AI for the “the fabrication or installation of personal photos that harm an individual’s reputation, honor, or dignity; manipulation or falsification of speeches, statements, or official communications; manipulation of any textual, audio, or visual content of individuals without their explicit consent; manipulation or falsification of personal, health, or professional data; [or] any other cases determined by a decision issued by the Minister, based on a proposal from the Artificial Intelligence Unit.” Violators face regulatory fines or up to three years in jail.

- Providing mitigation measures. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for [the] Public outline mitigation measures for both “deepfakes and misrepresentation” and “misinformation and hallucinations.” The former include watermarking, output verification and enhanced digital literacy. The latter include content verification and citation, content labeling and fact-checking.

- Using AI to counter mis- and disinformation. Egypt’s National AI Strategy, for example, notes that AI can be used to help detect “fake news” and asserts that the government can use AI to combat mis-, dis- and malinformation (MDM). Libya’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy also states that the government can use AI to counter MDM. Neither proposal explains how the government would use AI to do so.

- Setting value-based standards. Saudi Arabia’s AI Ethics Principles include instructions for AI developers: “Predictive models should not be designed to deceive, manipulate, or condition behavior that is not meant to empower, aid, or augment human skills but should adopt a more human-centric design approach that allows for human choice and determination.” The principles lay out how developers can accomplish this at every stage of the AI lifecycle, including by properly acquiring and processing data and by conducting periodic assessments.

- Noting the risks. For example, Israel’s Policy on Artificial Intelligence Regulations and Ethics states, “The proliferation of fake news and disinformation, with attendant risks to democratic governance, harms to fundamental rights and freedoms, wide-scale consumer manipulation, and the like. A discussion about the appropriate scope of disclosure for AI systems must take these broader concerns into account.” Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Government similarly note that government users of AI tools must take into account the risks arising from their use, such as misinformation and deepfakes.

Impacts on journalism

Bahrain’s prohibition on some forms of manipulated content may help prevent forms of technology-facilitated violence against journalists, such as deepfake nudes, and prevent their likenesses from being used in content they are not involved with. This would help protect journalists from violence, which could in turn enable journalists to safely work in the profession. On the other hand, the broad wording of the draft law may pose problems for reporters. It is not clear, for example, whether a reporter could be penalized for using AI to make minor edits to an image, nor is it clear how “damage” to an individual’s reputation is decided. Due to the lack of clarity and the threat of punishment, journalists may self-censor.

Attempts to use AI to counter mis- and disinformation are generally positive for the information space, and some early examples have shown this strategy can be effective; however, there must be clear boundaries between countering verified disinformation and censoring unwanted narratives.

Attempts to set standards and mitigation measures can provide news organizations and others with good practices to follow as they implement AI in their work, which will help prevent the further degradation of the information space. Because Saudi Arabia’s guidelines are not legally binding, however, this may lead to a split between organizations that choose to adopt these measures and organizations that do not; such a split could inadvertently further corrupt the information space by allowing bad actors, such as “disinformation for hire” firms, to hide their use of manipulated content, while more legitimate outlets that choose to adopt the measures might be viewed with distrust for admitting they use AI.

Countries who note the risks posed by AI-manipulated and synthetic content have taken an important first step, but they will need to further consider how best to address the issue to truly have a positive impact on journalism and the information space.

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

AI summary: In an effort to prevent bias and discrimination, several countries in the Middle East and North Africa are creating rules for how AI should be designed, which includes requiring audits, using diverse datasets and fining those who create biased systems. While these rules could help journalists make sure their reporting is fair, they may also make it hard for newsrooms to use AI to personalize content.

Approaches

The Gulf Cooperation Council’s Guiding Manual on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence Use in Member States lays out recommendations member states can take to prevent bias in AI, such as auditing datasets, establishing oversight processes, addressing the digital divide, engaging diverse stakeholders and ensuring diversity in access to AI systems. Both members of the Gulf Cooperation Council and non-members in the region have taken similar approaches to address algorithmic discrimination and bias in their AI proposals:

- Requiring algorithmic audits. Libya’s National AI Policy, Oman’s Public Policy for the Safe and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence Systems and the UAE’s AI Ethics Guide require developers to conduct algorithmic audits to prevent bias.

- Using diverse datasets. Saudi Arabia’s AI Ethics Principles, for example, call for AI systems to be trained on data that is “cleansed from bias” and “representative of affected minority groups” — and it lays out steps developers can take to ensure tools are unbiased at every stage of the AI lifecycle. Saudi Arabia’s Guidelines for Government further note the importance of understanding where the data comes from to prevent bias. The UAE’s AI Ethics Guide also lays out steps developers can take to mitigate and disclose the biases inherent in datasets, including hiring people from diverse backgrounds to work at every stage of the AI lifecycle. The UAE’s AI Adoption Guideline in Government Services also notes that the data used to develop AI models across government services “should be representative, otherwise AI decisions will turn out to be biased.”

- Improving users’ understanding of bias. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Government and Generative AI Guidelines for Public both feature components calling for an increased understanding of bias for users. The former implores government developers to “enhance users’ understanding and awareness of bias, the importance of diversity and inclusion, anti-racism, values and ethics, as this knowledge will contribute to improving their ability to identify biased content.” The latter calls on developers and end users to enhance their knowledge of bias to improve their ability to recognize biased content.

- Imposing fines. Article 25 of Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law imposes fines on those who “design programs or systems that result in discrimination between persons who enjoy equal legal status.”

Impacts on journalism

As journalists and newsrooms develop and deploy AI systems, they will have to ensure their AI tools follow best practices to avoid algorithmic bias and discrimination both to ensure their reporting remains objective and to ensure they do not fall subject to fines or other penalties. Even when using diverse datasets and with algorithmic audits in place, however, journalists should always ensure that a human confirms the accuracy of any AI-generated content.

On the other hand, national regulations can pose a challenge to newsrooms’ efforts to use AI to personalize content using more sensitive data. Bahrain’s draft law, for example, could potentially be used to penalize news organizations, depending on how “discrimination” is defined in the law and how the law is applied to the media sector. News outlets will have to walk a fine line between personalization and bias mitigation. To explain how they do this, newsrooms could consider publishing their own AI ethics policies, which should outline how they are using AI technology, how they are mitigating biases and discrimination, and how they implement human oversight of all AI-produced content.

Intellectual property and copyright

AI summary: Countries in the Middle East and North Africa are taking different approaches to handle intellectual property and copyright for AI, such as requiring licenses for content, creating new patent systems or updating current laws. These rules could help journalists by requiring AI developers to pay journalists for the use of their content to train AI models, but it is still important that new policies properly protect journalistic work.

Approaches

Intellectual property rights and copyright are covered in a handful of AI policies throughout the Middle East and North Africa, each one taking a slightly different approach.

- Mitigating copyright infringement. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Public lays out mitigation measures for intellectual property infringement, calling on generative AI developers to obtain licenses for any intellectual property they use in training data, which would prevent “indiscriminate data scraping.” It also requires AI developers to establish compensation mechanisms to pay creators whose intellectual property has been used to train AI.

- Developing a patent granting system. Egypt’s National AI Strategy outlines an initiative for an AI patent granting system, which would raise awareness of intellectual property protection and develop AI-specific patent categories for “AI inventions.” This part of the strategy is focused on enabling innovation, but it is not yet clear what the patent categories would be, nor is it clear who would own AI-generated content.

- Applying existing laws to AI. Jordan’s National Ethics Charter for AI explains that any data used to train AI models should respect intellectual property laws.

- Updating existing legislation. Oman’s National Program for AI and Advanced Digital Technologies, for example, suggests the government update the Copyright and Neighboring Rights Protection Act to account for generative AI, but it does not detail what updates should be made.

Impacts on journalism

The use of news articles and other journalistic content to train AI models for commercial use raises important copyright questions. Proposals that would mitigate this infringement by requiring AI companies to obtain licenses to use content and/or remunerate the content creators could provide an important lifeline for journalists and news organizations — many of whom report losing traffic to their original news articles due to AI.

A patent granting system is likely to benefit AI developers who create “AI inventions.” In some situations, it could also benefit journalists who use AI to produce original materials. Further clarity on this concept will be essential, though, and policymakers will need to include specific considerations for journalism and other forms of media.

As countries determine how best to update or apply their existing copyright laws, policymakers should also consider how best to protect journalistic content from copyright violations in the AI era.

Transparency and accountability

AI summary: Most of the AI policies in the Middle East and North Africa require transparency and accountability, using methods like audits, user notices and rules for who is responsible for AI-caused harm. These efforts can help journalists better understand and report on AI, but they also mean newsrooms may be held responsible for any damage caused by the AI tools they use in their work.

Approaches

Nearly all reviewed documents in the region included provisions for transparency and accountability, but they take a wide variety of approaches.

- Requiring audits. The UAE’s AI Ethics Guide, Egypt’s National AI Strategy and Qatar’s Guidelines for Secure Adoption and Usage of Artificial Intelligence all stress the importance of conducting audits to improve transparency.

- Building in appeals procedures. To ensure AI systems are transparent and accountable, the UAE’s AI Ethics Guide notes that AI systems should have built-in appeals procedures that would allow users to challenge “significant decisions.” The guide further suggests that “AI operators and AI developers should consider designating individuals to be responsible for investigating and rectifying the cause of loss or damage arising from the deployment of AI systems.”

- Informing users they are interacting with AI through labels or other notices. Israel’s Policy on Artificial Intelligence Regulations and Ethics states, “To the extent possible and in appropriate cases, individuals should be: (1) informed that they are interacting with an AI system, (2) notified if an AI system is being used to make recommendations or decisions involving them, and (3) provided with an understandable explanation of an AI-based recommendation or decision involving them,” echoing the UAE’s AI Ethics Guide. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Government and for the Public are slightly more specific, requiring government entities to communicate when using generative AI to interact with the public and to use watermarks to help consumers identify AI-generated content. Oman’s Public Policy for the Safe and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence Systems calls on developers to provide mechanisms to identify AI-generated content through labeling or explanatory notices to prevent misuse.

- Determining liability. The UAE’s AI Ethics Guide, for example, states that “accountability for the outcomes of an AI system lies not with the system itself but is apportioned between those who design, develop and deploy it.” Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law notes that anyone who suffers damage due to an AI system has the right to demand compensation from the programmer, processor or developer. Saudi Arabia’s AI Ethics Principles hold designers, vendors, procurers, developers and assessors, as well as the technology itself, ethically responsible and liable for an AI system’s decisions and actions, noting that these entities should be identifiable and take accountability for any damages.

- Calling for decisions to be both explainable and replicable. Oman’s Public Policy for the Safe and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence Systems requires AI developers to provide documentation explaining an AI’s decision-making logic and data analysis process; to ensure that AI systems are capable of providing understandable explanations of the decisions they make; and to ensure an AI documents all processes to enable future verification and analysis. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Government also state that transparency is needed across the design and implementation of an AI system, as well as in the product and its justifications of an outcome. AI systems’ decisions should be traceable, according to the guidelines, and companies should include an information section on their platforms.

Impacts on journalism

Transparency efforts are generally beneficial for journalism, as they can improve journalists’ understanding of how AI technology is being used and how it arrives at its conclusions, thus enabling journalists to better report on the technology and the entities using it.

These provisions will also impact the way journalists and newsrooms use and deploy AI. According to these policies, if journalists use AI in their reporting, the AI’s decisions must be auditable, explainable and replicable; but these standards are already a best practice for journalism.

Provisions that would inform users of their interactions with AI are also good practice for journalists. As journalists use AI, they will have to determine how best to inform the public of its use in order to maintain trust.

Finally, these proposals make clear that newsrooms can be held liable for any AI tools they develop and deploy, meaning media outlets will be responsible for any damage the AI tools they use cause; although, it is not yet clear what qualifies as prosecutable damage under these proposals. As such, journalists and newsrooms will have to ensure that the AI technology they use follows the above-mentioned guidelines of explainability, auditability and replicability, and newsrooms will have to have policy in place and staff to answer any questions users may have about the newsroom’s AI technology’s decisions.

Data protection and privacy

AI summary: Countries in the Middle East and North Africa are working to protect data and privacy in their AI policies by updating current laws, creating new ones, or setting up government agencies to oversee data protection. These rules can help protect journalists and their sources, but they may also be used to limit reporting.

Approaches

- Updating and applying existing legislation. In some cases, such as in Algeria, Egypt and Israel, the AI proposals recommend updating the country’s existing data protection laws to account for generative AI. Other proposals, such as Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Government and the Public, Qatar’s Guidelines for Secure Adoption and Usage of Artificial Intelligence and Oman’s Public Policy for the Safe and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence Systems, outline ways existing data protection legislation can be applied to AI models.

- Developing a data protection law. According to Libya’s National AI Policy, any processing of personal data must comply with the Personal Data Protection Law as soon as one is enacted.

- Creating or expanding an oversight authority. Egypt’s National AI Strategy calls for the creation of a personal data protection authority, while Algeria’s National Strategy for AI proposes expanding the Personal Data Protection Agency’s role in overseeing data protection and enforcing AI regulations.

- Incorporating privacy into the design of AI models. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for the Public note that privacy and security should be implemented into AI tools “by design.” Kuwait’s National AI Strategy notes the need to establish a “security baseline” in the development and deployment of AI that would “provide a structured approach to identify vulnerability, establish protective measures and enforce compliance with regulatory requirements.” Similarly, Oman’s Public Policy for the Safe and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence Systems requires developers to implement protective measures that ensure data privacy and security and the UAE’s AI Ethics Guide states that AI systems should “respect privacy and use the minimum intrusion necessary.”

- Providing consent provisions. Saudi Arabia’s Generative AI Guidelines for Public require generative AI service providers to provide users the option to either give or refuse consent to have their data used for AI model training purposes. The guidelines also require service providers to offer an option to remove all prompt history on request, in accordance with relevant laws and regulations.

- Prohibiting surveillance. The UAE’s AI Ethics Guide states, “Surveillance or other AI-driven technologies should not be deployed to the extent of violating internationally and/or UAE’s accepted standards of privacy and human dignity and people rights.”

Impacts on journalism

As explained in the Sub-Saharan Africa chapter, the African Union’s Continental AI Strategy can provide insight into some ways North African countries are thinking about data protection and privacy. The Continental AI Strategy calls on data and computing platforms to develop policies that facilitate sharing of non-personal data, and it recommends regional governments establish frameworks and protocols that align with the African Union’s Data Policy Framework. It also cites the African Union’s Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection, or the Malabo Convention, as an important guiding document. No countries in North Africa have ratified the Malabo Convention, however, meaning that it is not enforceable, but it may still hold normative power in shaping how these countries update their own data protection laws.

More concretely, data protection and privacy should be built into any AI system newsrooms develop or deploy; this is an important way to protect both end users and journalistic sources, especially in repressive environments. It is worth noting, however, that data protection laws can and have been used to stifle public interest reporting.

Proposals that prohibit the use of AI for surveillance could theoretically improve the safety of journalists and their sources. In practice, however, the UAE’s laws include exceptions for national security and public interest reasons, leaving the door open for continued government surveillance of journalists.

Public information and awareness

AI summary: Countries in the Middle East and North Africa are creating plans to increase public knowledge about AI through awareness campaigns, education, and accessible resources. While these efforts could benefit journalists by giving them the knowledge to cover AI, there are concerns that some governments may try to control how the media reports on the technology.

Approaches

The Gulf Cooperation Council’s Guiding Manual on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence Use sets the stage for the region by including a recommendation that member states raise awareness of and disseminate knowledge about AI by creating educational materials, running public awareness campaigns and carrying out joint training sessions. Approaches throughout the Middle East and North Africa follow suit.

- Running AI awareness campaigns. Algeria’s National AI Action Plan, for example, notes the need to “establish and run an AI Awareness and Literacy Program for the public and decision makers alike, through the media, conferences, workshops, and collaboration with educational organisations.” Egypt’s National AI Strategy calls on the government to partner with the media and influencers “to share positive news about AI,” as well as to partner with media organizations to distribute a survey about public attitudes towards AI. Kuwait’s National AI Strategy calls for public awareness campaigns to “demystify AI, raise awareness about its potential benefits and implications, and empower individuals to make informed decisions in the AI-driven world.” Libya’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy highlights the need for awareness-raising efforts, including through the issuance of press releases on AI news.

- Promoting AI literacy. Kuwait’s National AI Strategy features an initiative to promote digital literacy in the country, including among citizens, students and non-technical professionals. Libya’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy notes that AI awareness programs should be developed and implemented for public sector employees. It also features provisions to educate students on AI and to encourage community-wide AI literacy that can help develop smart solutions for the public good.

- Providing accessible resources. For example, Kuwait’s National AI Strategy includes an initiative to provide “accessible and user-friendly resources in Kuwait, such as online courses, tutorials, and interactive tools, to facilitate self-paced learning and skill development in AI-related topics.”

Impacts on journalism

AI awareness, literacy and education campaigns could benefit both the public and journalists. An AI-literate public would be better equipped to understand both benefits and harms of AI. These same campaigns could also potentially benefit journalists if they are included; in order to cover AI technology, journalists will need to be up-to-date on the latest developments in the technology industry and to understand how AI companies and their tools are impacting society. Regardless of whether or not it is stated explicitly in the proposals, journalists have an important role to play in sharing information about AI with the public, and it is important they have the knowledge to do so accurately.

Algeria, Libya and Egypt’s proposals all notably acknowledge the important role of journalists as purveyors of public information; however, Egypt’s call for the media to “share positive news about AI” suggests dictating how journalists cover technology. It is important that policymakers respect the editorial independence of the press, even when partnering with them on public awareness campaigns.

Conclusion

While journalists and journalism are not central to any AI policies, strategies or laws in the Middle East and North Africa at this time, the existing ones will impact the field. AI offers unique opportunities and risks to journalists in this region. On the one hand, newsrooms can develop and deploy rights-respecting AI to aid in their reporting. This can help newsrooms develop new forms of income, allow reporters to put out content that masks a source’s identity to keep them safe, and help outlets reach new audiences. On the other hand, AI can exacerbate existing threats that journalists face in the region, such as surveillance and technology-facilitated gender-based violence, and vague AI laws can be misused to attempt to silence reporters.

Share