TL;DR

Table of Contents

AI policy in the region

One of the most economically dynamic parts of the world, South Asia is home to a young, booming, technically literate population; technology companies willing to invest increasing resources in what they term ”emerging” and “frontier” markets; and governments toeing a fine line between caution and optimism about technology policy, particularly artificial intelligence. Most governments in the region have refrained from rushed regulatory proposals about AI; thus, the consequences for journalism are challenging to predict.

Recently surpassing China as the world’s most populous country, India has attracted the attention of global technology companies, drawn not just by the potential size of the market but also by a strong higher education sector, a technically skilled workforce, widespread proliferation of low-cost technology and a regulatory environment that has, in the last couple of decades, aimed to open up the country to more foreign direct investment. India’s approach to regulation is deliberate: the country aims to balance risks, innovation, human rights and local economic development.

Bangladesh, the region’s second largest economy, pushes for both innovation and harm-prevention in its AI approach. Bhutan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka have introduced an AI policy, law, and strategy, respectively.

There are no laws or policies impacting the entire region; although, it is worth keeping an eye on regional blocs for any future convenings and policy developments. In May 2025, Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), which includes Myanmar and Thailand but excludes Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Maldives, convened a workshop on “AI Standards for Efficiency in Telecommunications & ICTs: Shaping the Future Responsibility” in New Delhi in collaboration with the International Telecommunication Union. Aimed at promoting development of inclusive and ethical AI standards, the workshop was meant to be the first in a series to lay out pathways for future public-private collaboration in “creating technical standards to ensure AI systems are secure, interoperable, and globally aligned.” The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has not yet announced or convened any overarching AI guidelines for formal adoption across all member states.

By the numbers

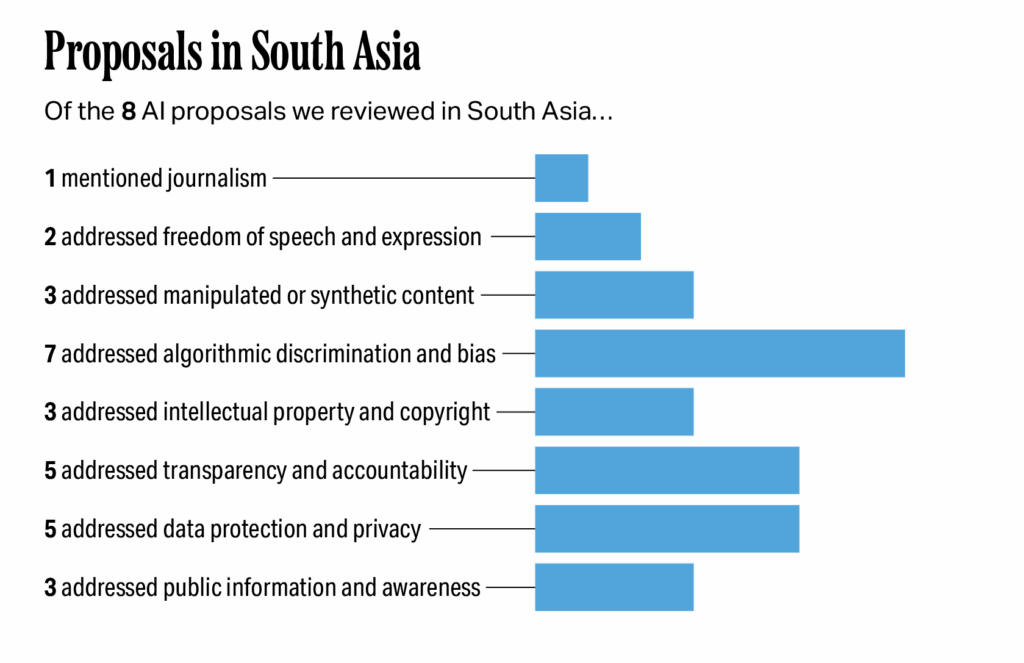

Of the eight AI proposals we reviewed in five countries in the region, one specifically mentioned journalism (or media); two addressed freedom of speech or expression; five addressed manipulated or synthetic content; eight addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; five addressed intellectual property and copyright; seven addressed transparency and accountability; seven addressed data protection and privacy; and four addressed public information and awareness.

Impacts on journalism and a vibrant digital information ecosystem

Each of these seven policy areas has the potential to have significant impacts on journalism and the information space across the region. Public information campaigns and related training could provide journalists with the skills and knowledge they need to effectively use and report on AI. Provisions encouraging human review and content labelling of AI-generated content could help journalists ensure they do not accidentally spread misinformation. In order to uphold the journalistic standard of objectivity, journalists and newsrooms will have to be cognizant of the biases of the AI systems they develop, deploy and report on. Like other regions, journalists in South Asia are facing difficulties when it comes to copyright in the AI era. The proposals we reviewed could help redirect traffic to news sites by requiring civil servants to double check AI responses and to cite their sources; they would also require journalists to take similar steps when using AI. In general, transparency and accountability requirements for AI would allow journalists to better access and understand AI systems’ data, thus enabling them to better report on the technology, but the proposals we reviewed currently fall short. As countries throughout South Asia further develop their data governance frameworks, newsrooms will be required to comply with these local regulations to ensure data privacy is built into any AI systems they use or deploy. Finally, the lack of consideration for freedom of speech in the reviewed AI proposals paired with the low press freedom rankings across the region could signify a negative environment for press conditions in the AI era.

Freedom of speech and expression

AI summary: Of the AI proposals reviewed in South Asia, only two mention freedom of speech or expression. Sri Lanka’s strategy mentions the need to balance controlling harmful AI content with protecting freedom of expression, and India’s Fairness Assessment highlights that AI systems should not impact individual rights. The fact that most AI proposals don’t mention freedom of speech, combined with the low press freedom rankings in the region, suggests a negative environment for journalism and upcoming laws in India could make it easier to censor journalistic content.

Approaches

Two AI proposals in the region mention freedom of speech or expression. They do so in different ways.

- Balancing the creation of harmful content with freedom of expression. Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI states, “Generative AI can accelerate the creation and distribution of misleading and harmful content. However, any efforts to regulate this must carefully balance the need to protect the public with the importance of upholding freedom of expression and ensuring access to information.” It does not go into further detail.

- Assessing AI’s impact on constitutional rights. India’s Fairness Assessment and Rating of Artificial Intelligence Systems states that AI systems should be classified as high, medium or low risk based, in part, on how “the outcomes affect users’ rights and freedom as per the constitutional and ethical considerations.” While it does not specify freedom of expression, it is implied since it is a guaranteed right under Article 19 of India’s Constitution. If an AI system is found to be high-risk if it is anticipated to impact an individual’s rights or freedom. This assessment is voluntary, however, so it is up to the company to determine whether they adhere to the findings from this standard.

Impacts on journalism

The omission of freedom of speech and expression in the reviewed AI policies does not necessarily mean that countries in South Asia do or do not support this right — nor does it signify that Sri Lanka and India care more for free speech than their neighbors. However, none of the countries in this region rank “open” in Article 19’s Global Expression report. Sri Lanka was the only country in the regionto improve its freedom of expression ranking in the last year, now coming in at “less restricted,” while India is categorized as “highly restricted.” Because freedom of speech creates the environment in which freedom of press can exist, the lack of consideration for freedom of speech in the reviewed AI proposals paired with the low rankings across the region could signify a negative environment for press conditions. Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 World Press Freedom Index reinforces this, noting that media concentration and political collusion threaten press freedom in several South Asian countries.

Manipulated or synthetic content

AI summary: Government proposals are focusing on human review of AI-generated information, requiring platforms to stop illegal content from being shared and suggesting that AI-created content be labeled. These regulations could help journalists by promoting transparency and accuracy, but some of the rules could also be used to censor them or create confusion about what is real.

Approaches

AI strategies, laws, and policy proposals in the region generally address manipulated or synthetic content in three ways.

- Calling for human review. Bhutan’s Guideline for Generative Artificial Intelligence Usage in the Civil Service notes the essential need to address AI-generated misinformation. The guideline explains that while generative AI might answer questions, those answers might not always be accurate; therefore, it is incumbent upon civil servants to verify and review AI-generated content before official use. If misinformation is spread due to a user’s carelessness, that individual faces legal liability for any harms caused.

- Requiring platforms to ensure AI does not make it possible for users to share unlawful content. India’s March 2024 AI Advisory requires intermediaries and platforms to ensure that use of AI models, large language models and generative AI “on or through its computer resource” does not make it possible for users to “host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, store, update or share” unlawful content.

- Calling for content labeling. India’s March 2024 AI Advisory further advises that if an intermediary permits or facilitates the creation of synthetic content or the generation or modification of text, audio or visual information, which could then be used as misinformation or a deepfake, they also label that content or embed it with a permanent unique metadata or identifier.

Impacts on journalism

Bhutan’s requirement of human review is not only applicable for civil servants; this same concept should apply to journalists who use AI for their own work or who report on AI outputs. By reviewing AI-generated content, journalists can ensure its validity, thus ensuring they do not contribute to the spread of misinformation. Likewise, content labeling can increase transparency in the information space and is generally a good practice for news organizations. However, because this portion of India’s AI Advisory is not legally binding, not all organizations will follow the labelling suggestion. This could lead to a split between organizations that choose to adopt these measures and those who do not, which could lead to confusion in the information space and inconsistent disclosure about content that is AI-generated. However, these rules in India’s AI Advisory will become binding if the proposed Draft Rules on Synthetic Labeling, which are currently under public consultation, become public (these draft rules were introduced in October 2025 and, because they fall outside the timeframe covered in this paper, were not analyzed in greater detail).

The provision in India’s AI Advisory requiring platforms to prevent users from sharing unlawful content is voluntary, but it does point back to the Information Technology Act of 2000, which has been used to block the social media accounts of journalists and news organizations.

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

AI summary: Several proposals in South Asia aim to prevent bias in AI systems by requiring companies to check for fairness during development, providing certification for fair AI and teaching people how to avoid and identify biased content. These efforts will require journalists to be aware of biases in AI tools they use or report on, and equitable access to AI could help journalists by allowing them to use AI tools in local languages.

Approaches

Several AI proposals in South Asia are attempting to address algorithmic discrimination and bias, with varying levels of commitment.

- Preventing bias by design. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy states that, by design, AI systems must “prevent from unintended direct/indirect prejudice, bias, and discrimination,” noting that to ensure this, AI companies must carry out compulsory evaluations, consider the diversity of those evaluating AI systems and assess potential risks during the procurement process. Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI notes the need to monitor data for potential biases. India’s March 2024 AI Advisory calls on intermediaries and platforms to ensure their AI models and algorithms do not permit bias or discrimination, but it does not explain how they should do this.

- Certifying fairness. India’s Fairness Assessment and Rating of Artificial Intelligence Systems provides a systematic approach to certifying fairness for AI systems. It “approaches certification via a three-step process involving bias risk assessment, threshold determination for metrics, and bias testing.” Third-party auditors could provide this fairness certification to AI companies.

- Avoiding bias in use. Bhutan’s Guideline for Generative Artificial Intelligence Usage in the Civil Service encourages civil servants to learn about bias, diversity, inclusion, anti-racism, values and ethics to improve their ability to identify biased content. It also notes that civil servants should be careful of the prompts they provide to generative AI systems to prevent the generation of biased or discriminatory content.

- Ensuring equitable access to AI. Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI further states that the country will develop and deploy AI solutions that “address societal challenges, improve quality of life, and distribute benefits equitably across all segments of society. We will prioritize responsible innovation, aligning AI technologies with ethical standards, human rights, and societal values …” Pakistan’s proposed Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act similarly states that the national AI commission shall “ensure equitable access and equal opportunities in the field of Artificial Intelligence to all citizens regardless of difference in religious, gender, ethnic, geographic, financial, or physical abilities” but it does not specify how. While not a policy, the Indian government launched both the IndiaAI Mission, which aims to “democratize computer access,” among other things, and BHASHINI, an “open-source multilingual AI initiative supporting 22 Indian languages,” which is a response to the challenge of securing inclusive data that reflects the diversity of Indian society.

Impacts on journalism

In order to uphold the journalistic standard of objectivity, journalists and newsrooms will have to be cognizant of the biases of the AI systems they develop, deploy and report on. If newsrooms are developing their own AI tools, they should consider bias and other risks at every stage of the AI lifecycle to ensure they are not exacerbating societal divisions. If newsrooms are using AI systems, they can follow the steps described in Bhutan’s guide for civil servants to try to prevent biased outcomes; however, these efforts can only go so far if an AI model is trained on biased data.

By ensuring equitable access to AI, governments can enable increased AI uptake throughout their societies; journalists, however, will act as important watchdogs as they report on how these technologies are used and impact society. The Indian government’s technology proposals may aid the independent efforts of citizen journalists by allowing them to use AI tools in local languages; industry collaborations with newsrooms could help prioritize algorithmic transparency in emerging AI tools.

Intellectual property and copyright

AI summary: Governments in South Asia are in the early stages of updating their intellectual property and copyright laws for the AI era, with Indian news outlets’ legal cases against major AI developers potentially providing a crucial test case for the entire region.

Approaches

A few countries in South Asia recognize the difficulties of establishing and enforcing copyright in the AI era.

- Guiding companies on Intellectual Property protection. In its National Strategy on AI, the Sri Lankan government details how it will provide “technology transfer services” to AI companies, which will explain guidance and support throughout the commercialization process, from intellectual property protection to business model development, to help academics and researchers “spin out their AI innovations into start-ups.”

- Updating copyright framework. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy notes that the National Strategy for AI will include an updated intellectual property framework to “incorporat[e] ownership rights, patents, and copyright regulations regarding AI models, AI-generated works, source code, and data.”

- Citing sources to avoid copyright infringement. Bhutan’s Guideline for Generative Artificial Intelligence Usage in the Civil Service explains that the sources upon which AI models are trained may be copyrighted and, as such, these models may reproduce copyrighted content in their output. The guideline notes that because generative AI does not always include citations in its outputs, it is up to civil servants to find and cite the right sources to avoid copyright infringement.

Impacts on journalism

Bhutan’s guideline hits on a significant tension facing journalism in the AI era: news content is often used to train AI models, but these models often do not cite the original source in their output, nor do AI companies always pay the copyright holders for use of the data. This can result in decreased traffic to news sites and revenue loss. On the other side of this tension lies journalists’ own use of AI: like civil servants, if journalists are using AI to gather information, they should confirm its veracity and find the original source to cite.

Sri Lanka’s plan to work with start-ups on AI could benefit news outlets who attempt to develop their own AI models, and Bangladesh’s plan to update its copyright framework could also provide much-needed clarity for how journalistic content is used in the AI era.

AI and copyright are still in flux in the region, as demonstrated by the lawsuits between news outlets and AI companies. India-based Asian News International (ANI), NDTV, Network18, the Indian Express, the Hindustan Times and the Digital News Publishers Association (DNPA) have sued OpenAI for allegedly using their news content to train ChatGPT without permission. OpenAI claims that this content falls under the “fair use” doctrine, as per Section 52 of India’s Copyright Act, which would allow the company to use the content without permission or payment to the copyright holder. However, the new India AI Governance Guidelines, which were published after the data collection period for this report, state that “fair dealing” exceptions “may not cover many types of modern AI training” — although the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade has yet to release its final recommendation. Further complicating the issue, India’s Personal Data Protection Act, which is in the process of being operationalized but falls outside the scope of this paper, includes a fairly expansive view of how companies can collect public data.

Similar court cases are ongoing in the United States, United Kingdom, Japan and other countries. In other jurisdictions, news organizations have addressed this copyright issue by forming paid partnership agreements with AI companies, but so far no such partnerships have been established in India or other countries in South Asia. The outcome of this legal case in India will likely be a bellwether for how publishers, AI companies and lawmakers in the rest of the region attempt to address this issue.

Transparency and accountability

AI summary: India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are working on AI policies to ensure transparency and accountability by certifying fairness, setting ethical standards and requiring documentation and audits. These efforts could help journalists by providing greater access to information about how AI systems work, which would allow them to better report on the technology and its limitations.

Approaches

AI strategies, laws, and policy proposals in the region generally address transparency and accountability in three ways.

- Certifying fairness. India’s Fairness Assessment and Rating of Artificial Intelligence Systems states that governments, businesses and non-profits can pursue fairness certifications to demonstrate their efforts to root out bias in AI systems, which can help build “trust, equity, and transparency among the people.” It further states that “citizens would be the beneficiaries of fairness certification.”

- Establishing ethical standards. Pakistan’s Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act, for example, calls on the national AI commission to “make the processes and procedures of collection, storage, and usage of data in Artificial Intelligence systems more accountable, transparent and translućent,” as well as to “ensure implementation on the principles of accountability, privacy, safety, security through usage of Artificial Intelligence technologies.” Likewise, Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI states that the government “shall establish robust ethical standards, privacy measures, and security protocols in line with international frameworks to create a trustworthy AI environment. We will ensure transparency in decision-making processes, respect individuals’ privacy rights, and uphold principles of fairness and nondiscrimination.” It does not specify how this would be achieved.

- Requiring documentation and audits. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy requires AI systems, by design, to document the datasets, processes and algorithms “in a standard way to allow for traceability and transparency.” It also requires AI systems to establish “mechanisms to ensure AI compliance with regulations and standards through regular audits and assessments.” The policy does not specify how this would be achieved.

Impacts on journalism

Transparency is not a panacea for building more trust in journalism, but it can go a long way in helping journalists be more upfront about the strengths and limitations of their sources and their technology-assisted reporting processes. In general, transparency and accountability for AI would allow journalists to better access and understand AI systems’ data, thus enabling them to better report on the technology.

Pakistan’s AI Regulation Act, however, currently falls short; it mentions algorithmic transparency but does not mandate explainability or accountability for AI-driven decisions. Thus, AI companies are not required to follow these steps, meaning the data might not be accessible to journalists or the public.

Bangladesh’s policy requiring documentation of algorithmic processes could have implications for journalism chatbots and more public-facing news interface technologies. These implications pertain to data collection and processing, purpose limitation, and data security, as is the case in Europe with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Future legislation, if building on Bangladesh’s policy, could further strengthen transparency measures by ultimately making individuals aware that they are interacting with AI (e.g., chatbots), or that content they are interacting with was AI-generated. Bangladesh’s policy may also aid the work of journalists more broadly by making it easier for them to report on AI systems and their developers.

Stronger transparency obligations and enforcement could also encourage news organizations themselves to be more transparent about their sources, data and even financials. Research conducted in India, the United States, the United Kingdom and Brazil suggests such transparency measures can make readers more likely to trust news organizations.

Data protection and privacy

AI summary: To ensure the safe and ethical use of AI, countries in South Asia are working to establish data governance frameworks, strengthen data protection, and build privacy and data security into the AI lifecycle. As these regulations are developed, newsrooms will need to follow them to protect their reporters and sources; however, these regulations could be misused to stymie public interest reporting.

Approaches

AI strategies, laws, and policy proposals in the region generally address data protection and privacy in three ways.

- Establishing a data governance framework. Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI lays out how the country will develop and implement a new data strategy that supports Sri Lanka’s AI initiatives. The strategy will focus on three primary objectives: leveraging data as an asset, ensuring responsible data practices and promoting collaboration. To achieve this, Sri Lanka will establish a data governance framework to ensure compliance with relevant and upcoming laws and regulations, such as Sri Lanka’s Personal Data Protection Act (2022), the Right to Information Act (2016), the Electronic Transactions Act (2006), the forthcoming Cyber Security Bill and amendments to the Sri Lanka Telecommunications Act. The data governance framework will seek to achieve three key objectives: ensure relevant data is collected, standardized and accessible to appropriate stakeholders; guarantee the correctness and quality of the available data and developing processes for continuous assessment and improvement of data quality; and address ethical considerations related to data collection, storage and use.

- Strengthening data protection. Pakistan’s Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act, for example, calls on the national AI commission to “strengthen telecommunication networks, digital infrastructure, data governance, data protection, and cybersecurity,” though it does not specify how it should do so.

- Incorporating privacy and data security into the AI lifecycle. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy outlines how privacy should be incorporated into the development and use of AI technologies, stating that “models shall be trained with minimal use of potentially sensitive or personal data; personal data usage will require valid consent, notice, and the option to revoke; privacy measures like encryption, anonymization, and aggregation will be applied; [and] mechanisms shall allow users to flag privacy and data protection issues during data collection and processing.” Likewise, Bangladesh’s policy explains that the vulnerability of AI systems should be addressed through rigorous assessments and data validation, governance procedures and response protocols.

Impacts on journalism

While the journalism sector is not directly mentioned in any of the proposals, it will likely be impacted by them. As countries throughout South Asia further develop their data governance frameworks, newsrooms will be required to comply with these local regulations to ensure data privacy is built into any AI systems they use or deploy. Such data protection can help protect their reporters and sources.

As in other regions, though, data protection laws can be misused to stifle public interest reporting. As such, policymakers should consider the impact their AI proposals can have on the news industry and consider exceptions within the laws to protect journalists’ ability to carry out investigations — as the Press Club of India and 21 media organizations have asked policymakers to do in response to India’s 2023 Digital Personal Data Protection Act. Though this law does not specifically address AI directly and, thus, was not part of our data set, it is worth highlighting since it is in the process of being operationalized and because of the significant press freedom concerns it has raised.

Public information and awareness

AI summary: Countries in South Asia are working with global groups to develop AI policies and are starting to train workers, establish school programs and launch public campaigns to raise awareness about artificial intelligence. These efforts could help journalists by giving them the skills to better understand and report on AI, even though the plans do not mention them directly.

Approaches

South Asia is drawing inspiration and financial support from global bodies such as UNESCO as countries seek to develop AI policies, though at this stage, AI literacy appears to be more of an update to existing curriculum rather than a standalone initiative.

- Training the workforce. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy, for example, includes an objective to carry out “tailored training and skills programs [that] will address the AI skills gap in the workforce.”

- Establishing AI programs with educational institutions. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy further lays out a plan to carry out national campaigns targeted at educational institutions to encourage them “to establish and facilitate AI and data clubs.” Furthermore, Sri Lanka’s 2024 National Budget specifically allocates funding for new AI degree programs at state universities, in line with the country’s AI strategy.

- Raising public awareness. Sri Lanka’s National Strategy on AI lays out how the country will implement a public awareness campaign on AI: “We will develop engaging educational content on AI in Sinhala and Tamil for dissemination through mass media channels, such as television, radio, and social media. This content will explain key AI concepts, highlight potential benefits and risks, and emphasize the importance of AI skills in an increasingly digital future. By leveraging popular media and through collaborations with the private sector, we will reach a broad cross-section of society and foster a baseline understanding of AI.” Similarly, Pakistan’s proposed Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act, which would establish a national AI commission, calls on the commission to “take proactive steps to create public awareness for positive and productive usage of Artificial Intelligence technologies for the benefits of the people.”

Impacts on journalism

These initial developments, especially the support and best practices shared by international organizations such as UNESCO, are promising for the media sector. Even though they do not explicitly mention a role for journalists, they include provisions that could empower journalists to critically evaluate media content and could foster an informed society by advocating for greater information literacy among the public. Programs to train the workforce and students on AI, as well as public information campaigns, could benefit journalists — especially if some of these programs specifically target professional journalists and student journalists. This education would allow journalists to engage with AI for their own work, as well as to better understand and better report on AI.

Conclusion

South Asia is one of the world’s most populous regions and home to rapidly advancing economies. Combine that with linguistic diversity and rapid adoption and proliferation of technology, and you have a group of countries whose AI policies will have far-reaching implications for journalism and beyond. As policymakers in South Asia think about how best to regulate AI, they should not only consider how these technologies can impact their economies, but also how these technologies can impact their information ecosystems, and the information ecosystems of their neighboring countries — both positively and negatively. Policies do not always need to mention journalism by name, but policymakers should still form working groups to assess how their proposals might affect journalism and determine how best to prevent negative consequences before these regulations are implemented.

Share