Table of Contents

AI is revolutionizing the news industry. In CNTI’s 2024 survey of 430 journalists, AI was top of mind for three-quarters of them, and nearly half said their organizations are not paying enough attention to how AI can help their work, harm their work or both.

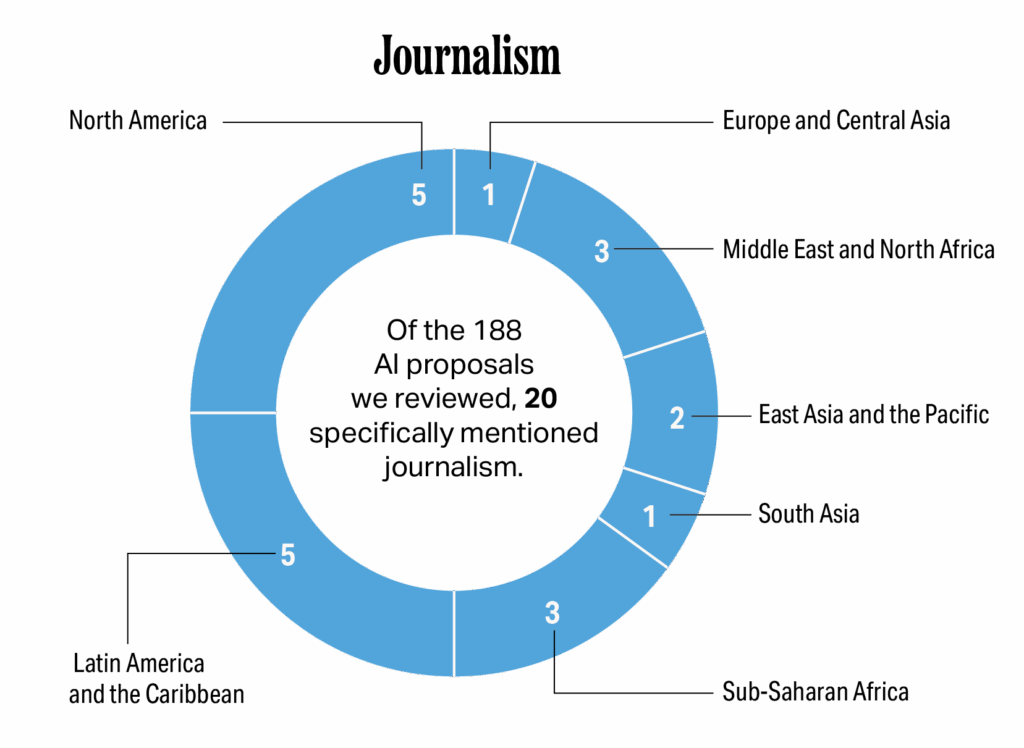

Whether newsrooms are paying enough attention or not, however, many governments are adopting AI strategies, policies and laws. These regulatory attempts rarely directly address journalism and vary dramatically in their frameworks, enforcement capacity and level of international coordination, but they will almost certainly have an impact on journalism and the digital information environment. To understand exactly how regulation is, or could be, impacting journalism, we reviewed 188 national and regional AI strategies, laws and policies that collectively cover more than 99 countries.

The analysis is structured around the seven regions of the world, as identified by the World Bank — North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, and South Asia — and around how regulatory activity in each of these regions addresses seven policy components that, based on the research of CNTI and others, are particularly relevant to and likely to impact journalism:

How We Did This

Our review includes documents put forward between January 2022 and June 2025. While regulations and strategies on AI existed prior to this period, they were excluded because they pre-date the widespread public release of generative AI systems, occasioned by ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022, and therefore do not reflect subsequent policy shifts.

Selection of laws and policies

Out of necessity, our sampling approach varied by region and by country. In North America, especially the U.S., there were too many bills to take a comprehensive approach. In this case, we selected AI legislation that represented a range of approaches, and prioritized regional/state diversity rather than likelihood to pass, consistent with our goal of understanding the breadth of regulatory approaches.

In other regions, such as Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and East Asia and the Pacific, we were able to compile a near-complete list of relevant documents from each individual country’s legislative resources and review the majority of bills and strategies. For countries with more than 50 bills at the national level, such as Mexico, we prioritized comprehensive bills over those that sought to create committees or institutes, amend current laws or address highly specific issues. In all these cases, secondary sources (e.g., law firms, academic articles) were used to verify the status of various proposals in the legislative process.

In Europe, we did not review individual strategies or laws for European Union member states since they automatically fall under the EU AI Act. EU candidate states are also required to pass legislation that aligns with the EU AI Act, so we noted when candidate states had separate strategies or policies in place.

In cases where a country had a bill, strategy and/or policy, we prioritized the legally-binding bill(s) over non-binding strategy documents. We did not count white papers or other government-sponsored research papers in the 188 documents we reviewed, but these papers were sometimes used to assess impacts on journalism.

Wherever possible, we reviewed bills, strategies and proposals in their original language. In addition to English, our research team includes members proficient in Spanish, French and Portuguese. For many other languages, we used high-quality English translations provided by law firms, research groups or governments themselves. For some documents, especially those from East Asia, we used machine translation. In these cases, our understanding was supplemented and confirmed by secondary sources (which are cited wherever appropriate). All machine translated quotes in this report have been confirmed by a human translator.

We focused on documents that used the term “artificial intelligence,” but definitions were not always consistent across laws or policies, even within a single country. (Many policies we included also used additional AI-related terms like “deepfakes.”)

As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI.

Explore the proposals

CNTI reviewed 188 national and regional AI strategies, laws and policies around the world to determine how they impact journalism. We focused our analysis around how regulatory activity addresses seven policy components that are particularly likely to impact journalism. Use the below map to explore each of the policy documents we reviewed and to see what journalism-related topics they include. Use the column on the left to see which documents mention a specific topic, or click on a country to see the list of its documents and the topics covered in each.

Key findings: The landscape

The governance of AI is increasingly complex and varies dramatically by country and industry.

The broad range of governance instruments in play include legally-binding regulation at every level of government, corporate policies, industry standards and many other types of documents. AI applications are being introduced across sectors: some of them, such as banking and health, are already heavily regulated, while others are much more lightly regulated. Even among national-level legislation, there is tremendous diversity in scope: some bills are sweeping and comprehensive, while others comprise small edits to existing laws or address AI in narrowly-defined use cases like online shopping, mammograms or road accidents. Others create new agencies, committees or councils to operationalize vaguely laid out principles. The law-making process varies by country, as do the stakeholders involved. There is also variability in countries’ power to impact technology companies. In some smaller markets, companies may consider pulling out rather than comply with regulations, especially if those regulations are burdensome or do not align with the requirements of larger markets. Furthermore, some countries — the United States among them — have dozens or even hundreds of bills in the pipeline, making it impossible to conduct an exhaustive review. While we offer numbers wherever possible to give a sense of scale and proportion, our research examines the breadth of policies, strategies and laws rather than providing a full audit.

As with all policy proposals, it is important to consider the AI documents we reviewed in their individual country contexts and in relation to pre-existing laws in those countries and regions. Even if journalism or data privacy is not explicitly mentioned in an AI document, for example, existing protections for these rights may supersede new AI proposals. It is also important for policymakers to coordinate with experts to determine whether their AI policy proposals are technologically feasible as they consider replicating the documents reviewed in this paper or originating new AI policy proposals.

Policies don’t have to mention journalism by name to impact it.

Twenty of the 188 documents explicitly mentioned “journalist,” “journalism,” “news,” “media” or “news media.”

When these terms do appear, they range from passing references to the field to laws whose primary concern is the practice of journalism. This by no means is a suggestion that more documents should directly name journalism. Calling out the journalism field in policy documents frequently has its own pitfalls: Once governments define “journalism” or “news,” those definitions can be weaponized against the news media. Instead, it is important that policymakers are aware of and think through potential impacts of directly naming or not naming journalism and news.

- Four documents (from Bahrain, Chile, Costa Rica and Kenya) identify journalists or media workers as stakeholders, but go no further. Three others (from the African Union, Panama and Serbia) specifically identify the field of journalism as an important audience for educational materials and reskilling.

- Four documents (from Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho and Sri Lanka) emphasize the importance of news media as a communications channel for public awareness campaigns, with varying assumptions about editorial independence from government.

- One proposed law (from Ecuador) attempts to intervene in polarization and fragmentation by requiring providers of content recommendation algorithms to include content from a broad range of media outlets.

- Five different bills and laws exempt journalism from specific provisions: China’s Interim Measures on Generative AI say that other journalism laws supersede it; three U.S. bills would exempt news media from specific restrictions on deepfakes in the context of both reporting and advertisements (Illinois, New Hampshire and South Dakota); and Brazil’s proposed law grants exemptions to some forms of copyright violation for journalistic or research purposes..

- Two proposed laws — both from the U.S., one in New Jersey and one in New York — would specifically regulate the use of AI in journalism.

Transparency and data protection are the two topic areas (among the seven studied) that come up most frequently.

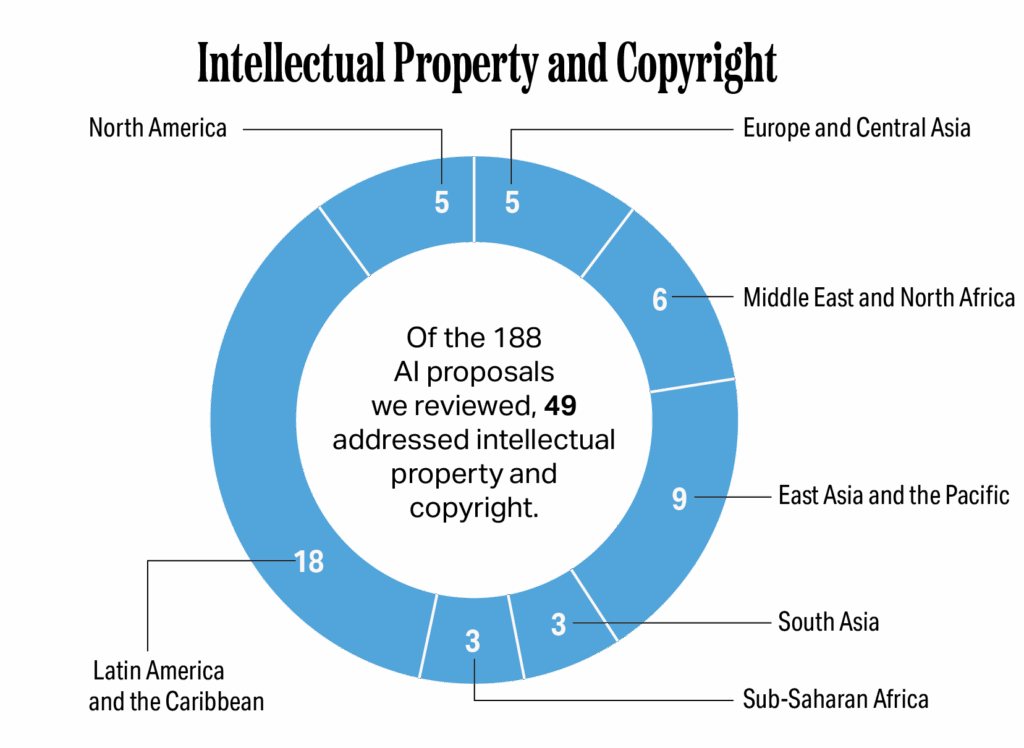

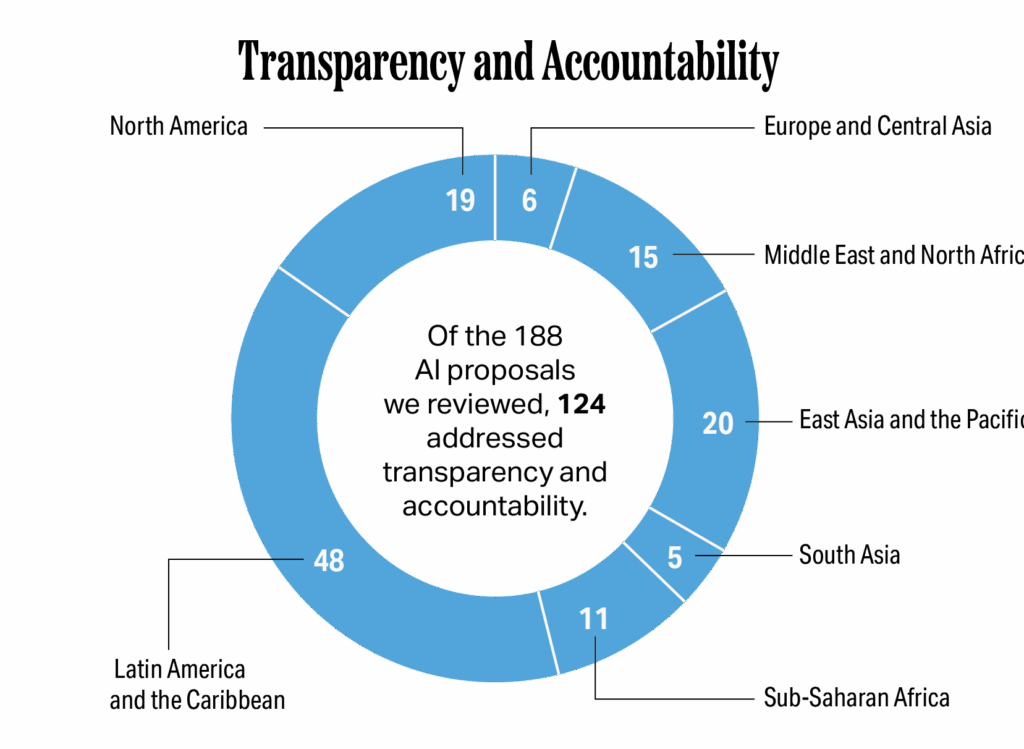

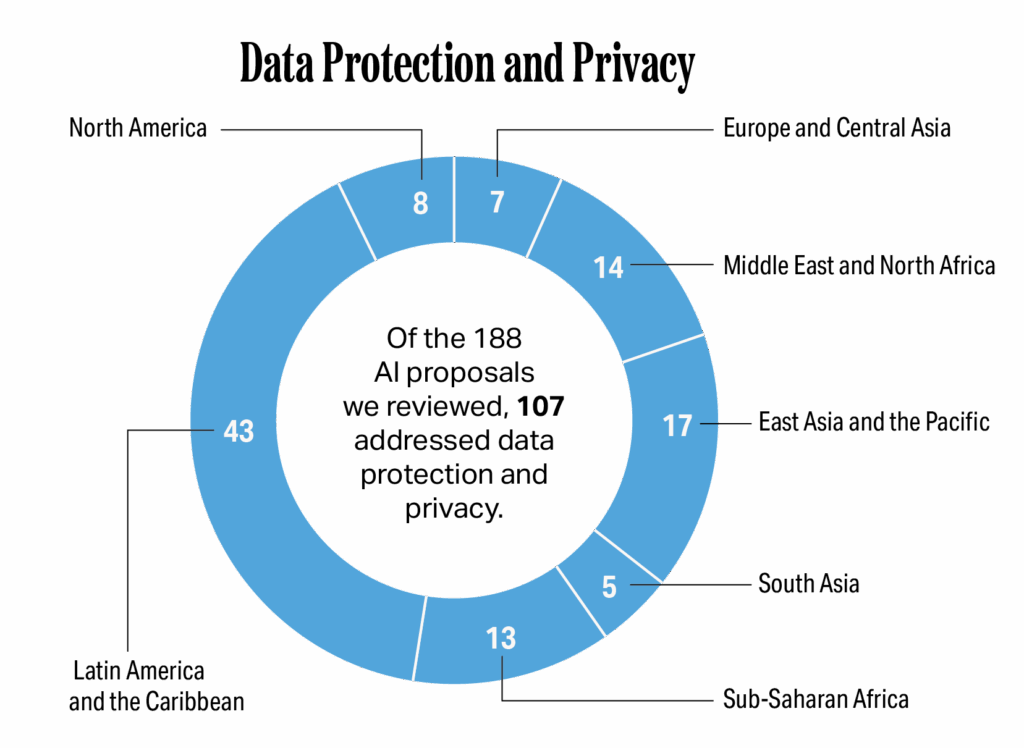

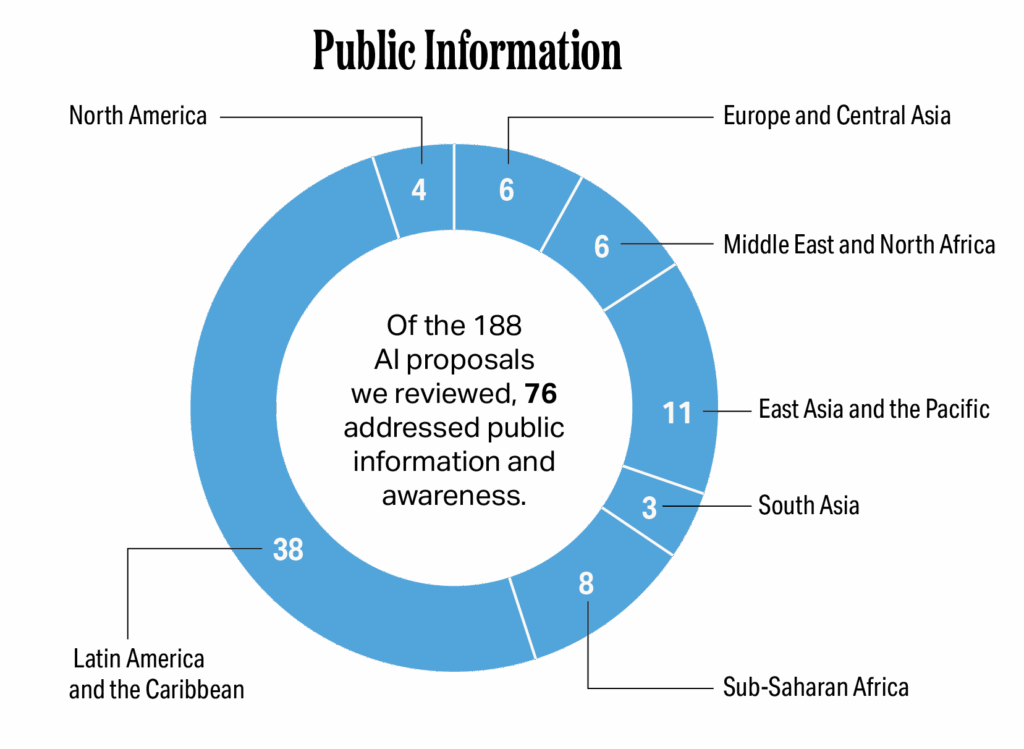

Of the 188 AI strategies, laws and policies we reviewed, 124 addressed transparency and accountability; 107 addressed data protection and privacy; 92 addressed algorithmic discrimination and bias; 76 addressed public information and awareness about AI; 64 addressed manipulated or synthetic content; 49 addressed intellectual property and copyright; and 19 addressed freedom of speech and expression. Each document could be counted in multiple categories. In all seven regions, either transparency or data protection was the most common topic. In every region, more than half of the documents we reviewed addressed transparency and accountability. Likewise, in every region, more than half of the documents we reviewed addressed privacy and data protection, with the exception of North America, which only featured the topic in eight of the 29 documents we examined. The emphasis on transparency likely responds to a key challenge for accountability: the opaqueness of many AI systems leaves even their creators without a full understanding of how they work, let alone policymakers. Meanwhile, the salience of data privacy is to be expected, since it has been a key issue in technology governance over the last ten years. At least four out of five people around the world are protected by a national-level privacy law.

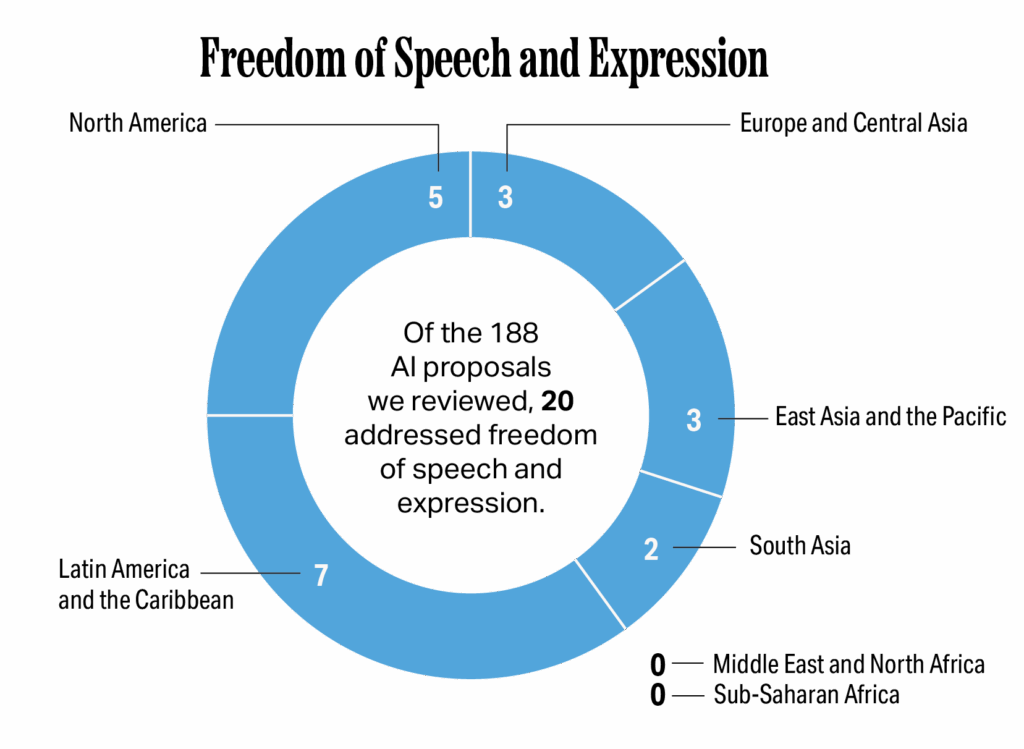

Freedom of speech and expression come up least often.

While policymakers regularly express concern about AI’s impacts on the information environment, references to freedom of speech and expression are infrequent across regions. In fact, these topics did not appear in any documents we reviewed from either the Middle East and North Africa or Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, the documents we reviewed addressed two very different concerns: Some, like Malaysia, addressed the possibility that using AI would threaten fundamental human freedoms, while others, like Venezuela, addressed the possibility that regulating AI would threaten human freedoms. The latter was more common in the United States than elsewhere, but both issues came up across regions. The EU’s AI Act highlights both concerns, emphasizing that AI systems can violate fundamental freedoms but also that labeling obligations do not restrict free speech. One resolution, New Jersey’s AR 158, instead focuses on freedom of speech about AI by urging technology companies to embrace stronger whistleblower protections. We note that the absence of explicit language about freedom of speech or expression does not necessarily indicate an absence of concern; in many countries, these freedoms are guaranteed in foundational legal documents, like constitutions, that supersede all other laws or policies. The certainty around the upholding of those foundational documents, however, cannot be guaranteed.

Key findings: The topics

Freedom of speech and expression

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 20 address freedom of speech and expression directly.

CNTI’s analysis finds that when freedom of speech and expression are recognized, it generally has positive implications for journalism. This demonstrates an understanding of the importance of this freedom and an acknowledgement of how AI can impact it. Because it is often only included in preambles or as a guiding principle, however, these policies often do not specify how they are going to protect these rights. Examining the range of existing levels of press freedom, both across and within regions, is foundational to understanding how these policies may be used.

Of the few concrete policies about freedom of speech and expression, most are likely to benefit journalism. Several countries ban AI systems that do not respect freedom of expression, but they do not specify how or what uses of AI systems would fail to respect fundamental freedom. For example, Argentina’s Bill 2573-S-2024 prohibits the use of AI “which violates fundamental human rights such as privacy, freedom of expression, equality or human dignity.” Other countries recognize trade-offs: In order to ensure that algorithmic content recommendation does not violate freedom of expression, Ecuador’s Organic Law for the Regulation & Promotion of AI in Ecuador requires clear terms and conditions, human supervision, accountability reports and an appeals process. These provisions would make it more difficult for journalists to be subject to censorship at the hands of an overly conservative algorithm.

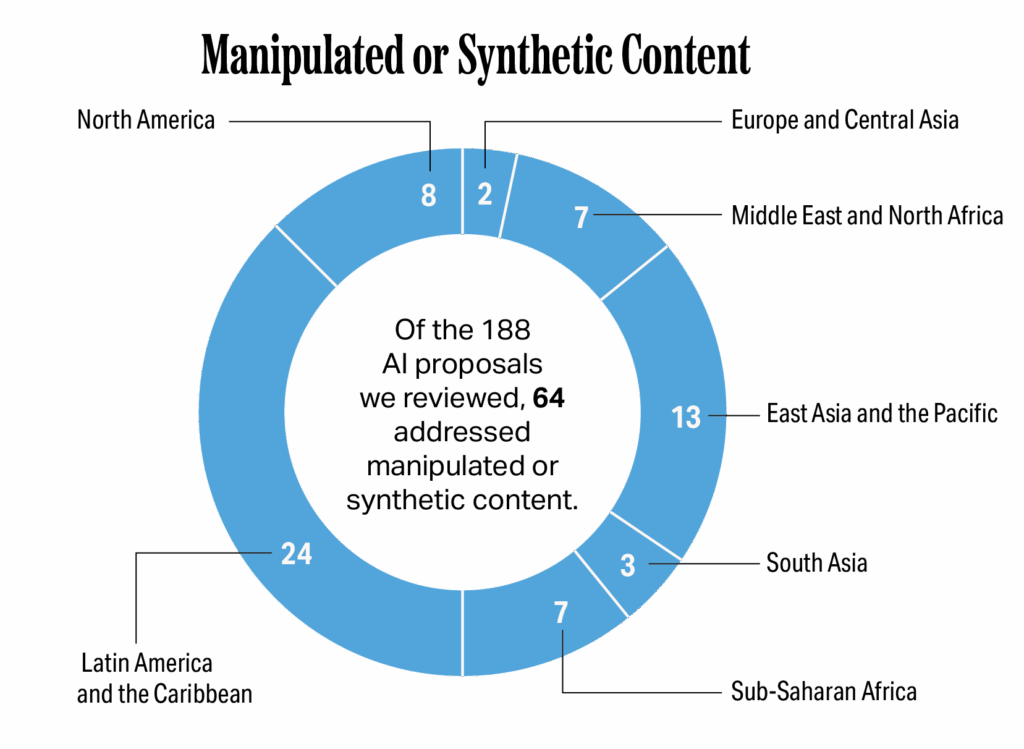

Manipulated or synthetic content

Of the 188 documents we reviewed, 64 address manipulated or synthetic content directly. At least two documents from each region contain provisions about this issue.

CNTI’s analysis finds that attempts to prevent the spread of false information and highlight the provenance of information are broadly positive for journalism and the information space — but these efforts must be scrutinized to ensure they do not infringe on freedom of expression.

For example, some proposals may protect journalists from technology-facilitated gender-based violence and other forms of AI-generated harassment. When a journalist is targeted with a deepfake, it can push them into silence, decrease their credibility and even drive them to leave the field. By banning explicit deepfakes, the United States’ Take It Down Act, Mexico’s Ley Olimpia and Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law would prohibit such attacks on journalists.

However, some of these proposals may end up penalizing journalists. For example, the United States’ 2025 Take It Down Act prohibits the nonconsensual publication of both authentic and AI-generated intimate images and requires online platforms to remove such images. It does not, however, include safeguards against bad-faith or fraudulent takedown requests, which some advocates say could be used to wrongly censor journalism.

Moreover, some provisions could potentially be used by the government to target journalists for reporting it does not like. Bahrain’s draft AI Regulation Law would prohibit using AI to “upload or install personal images that damage an individual’s reputation or dignity; [… or …] modify, edit, or tamper with textual, audio, or visual content related to individuals without their explicit consent.” These provisions are sufficiently vague that they could potentially be weaponized against journalists for innocuous changes, like editing the levels of an audio recording to make it clearer.

Finally, some proposals could impact journalists’ ability to use AI to protect their sources. The Dominican Republic’s proposed Bill 563, for example, would ban the use of deepfakes to alter videos and punish violators with prison terms and hefty fines. Because it does not include an exception for journalism, even when it is labeled, this could prevent journalists from using AI for legitimate purposes, such as to create an avatar of a source who wishes to remain anonymous for their safety.

Many laws also treat synthetic audio, images and video differently than synthetic text, increasing complexity in this space.

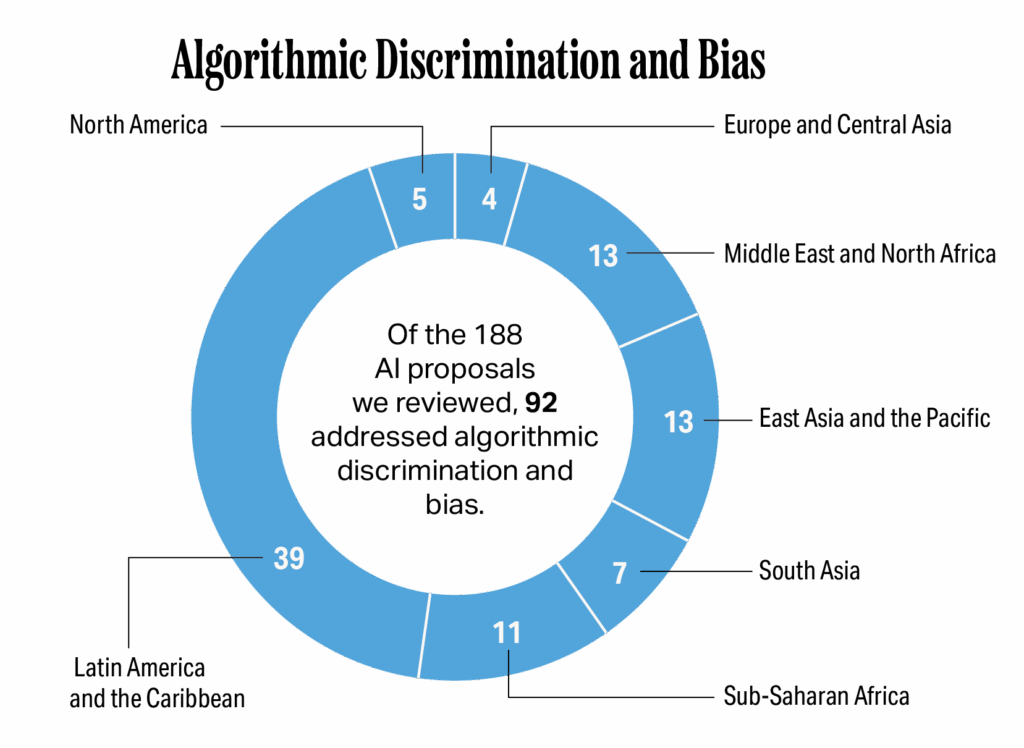

Algorithmic discrimination and bias

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 92 address algorithmic discrimination and bias directly.

Some laws would limit the tools that news organizations can use for decision-making, but these laws would not uniquely impact this sector — they typically focus on the use of AI tools for hiring and other consequential decisions, and would apply universally. News organizations would simply have to comply with these regulations.

However, policies that focus on bias in content recommendation systems could potentially have strong impacts on the reach of journalistic content. Content recommendation systems impact the content people see online, especially on social media platforms. Some news organizations also use them to suggest content to audiences. If social media platforms are required to recommend a diversity of sources and opinions, this would impact the reach of journalistic content, but it’s hard to tell if it will extend or limit that reach. Some AI policies — particularly in the EU — would limit the recommender tools used by social media platforms, but not by news organizations themselves, making the impacts unpredictable. Elsewhere, such as in Ecuador, provisions would require news organizations to scrutinize their personalization or content delivery tools, such as AI-powered, customizable homepages.

Other documents, such as those in Bangladesh and Lesotho, would push journalists and newsrooms to be more cognizant of biases in tools they use to analyze data or create content, especially if these provisions require representative or diverse training data. Because journalists already prioritize objectivity, such awareness falls under good journalistic practice and is unlikely to penalize journalists.

Looking beyond journalistic uses of AI, some proposals create registries and audits, which may facilitate journalists’ ability to conduct accountability reporting on AI more broadly. For example, Lesotho’s Draft Artificial Intelligence Policy and Implementation Plan calls on the country’s AI regulator and policymakers to develop “bias mitigation programs,” by mandating bias audits, providing open-source tools for bias mitigation and detection, and training developers and other stakeholders on bias prevention. This could grant journalists greater insight into how these technologies work, thus improving their reporting capability and increasing public accountability. It could also make it easier for them to select appropriate tools for their professional use.

Intellectual property and copyright

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 49 address intellectual property and copyright directly. At least three documents from each region included this policy component.

Copyright and intellectual property regulations are particularly complicated because different countries’ laws are incompatible with each other, and few have reckoned with major shifts in distribution made possible by the internet.

We found that some bills and laws require licensing and compensation for the use of copyrighted material to train AI models. Colombia’s Bill 293 states that beyond an exception for scientific uses, developers cannot use copyrighted content to train AI without prior and explicit consent. On the other hand, the Digital Single Market Directive of the EU AI Act, for example, does allow copyright holders to ‘opt-out’ of their content being used as training data for commercial purposes. The bill in Colombia also gives copyright collectives the right to authorize, prohibit, or restrict the use of works under their management, and they can demand just and equitable remuneration in order to license that use. These legal provisions will likely have positive financial impacts for journalism producers if they can be enforced.

At the same time, a number of documents mention the importance of protecting existing copyright and intellectual property laws without necessarily specifying how AI systems — particularly those using data in training models — fit into these legal foundations, let alone offering a comprehensive assessment of the value of these interactions with digital content.

For example, China’s generative AI regulation stipulates that both deployers and developers need to comply with intellectual property laws in the country, but it does not specify how AI systems and AI-generated content fit into those laws.

Japan, on the other hand, takes one of the most permissive stances, allowing the use of copyrighted works for AI training regardless of purpose, so long as it does not unreasonably prejudice the rights-holder’s interests. These divergent approaches raise the issue of interoperability when models are trained globally and deployed across borders.

The matter of intellectual property and AI is far from settled, though. In November 2025, a court in the United Kingdom found that AI models are subject to copyright infringement claims; however, the lawsuit did not answer the question of whether using copyrighted materials to train AI models falls within the U.K.’s “fair dealing” provisions. Courts in the United States have taken differing views, with two judges in California ruling that AI companies’ use of copyrighted materials to train LLMs constitutes “fair use” because the work is “transformative,” albeit with caveats and for different reasons, while a judge in Delaware ruled that a different AI company’s use of copyrighted materials was not “transformative” and, thus, did not meet “fair use.” This area will continue to evolve as ongoing lawsuits determine whether copyrighted material can be used to train AI models around the world, including in the U.S., India and Japan.

What is becoming clear is the need to holistically address the value of the various kinds of uses of and interactions with digital content in building AI models and beyond. Current policy approaches tend to dilate between narrow licensing regimes and permissive exceptions, but few adequately balance creators’ rights, developers’ needs and the public interest, let alone the vast array of content itself.

Transparency and accountability

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 124 address transparency and accountability directly. At least three documents from each region included this policy component.

CNTI’s analysis finds that their impact on journalism will likely vary depending on whether transparency obligations fall more heavily on developers or deployers. If they fall on developers, such as in Malaysia, it will be easier for journalists to assess whether third-party tools are valuable to their work; if they fall on deployers, like in this Argentine proposal, journalists, as deployers, would be held responsible for choices made by third-party companies which could lead to greater attentiveness among journalists, and, if not, to unanticipated lawsuits. Several documents, however, fall somewhere in between. The United Arab Emirates’ AI Ethics Guide, for example, states that “accountability for the outcomes of an AI system lies not with the system itself but is apportioned between those who design, develop and deploy it,” meaning journalists could be held accountable at any stage of the process.

We also found that, in general, transparency requirements can make it easier for journalists to report across a range of topics and sectors. For example, California’s AI Transparency Act requires transparency on the data used to train AI models, which would increase public understanding of the tools and, thus, allow journalists to better assess these models.

Some proposals would also require news organizations to label AI-generated content to ensure the public recognizes when it is being used. New York’s proposed Senate Bill S6748, for example, would require publications to “conspicuously” identify at the top of a page or webpage when AI is used to either partially or wholly create an article, image, video or other piece of content. Such requirements could potentially be a form of “compelled speech” or could reduce trust in the content.

Data protection and privacy

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 107 address data protection and privacy directly.

AI systems and tools are trained on vast quantities of data, and many countries have comprehensive privacy legislation in place that will interact with AI regulation in complex ways.

AI legislation, policies and strategies that address data protection and privacy typically do not consider the specific needs of journalists, who require access to sensitive data for investigative reporting. Bangladesh’s National Artificial Intelligence Policy, for example, states that “personal data usage will require valid consent, notice, and the option to revoke.” Requiring journalists to receive consent before using personal details, however, could inhibit investigative reporting on corruption, human rights abuses and more, given that the politicians, business leaders and others in question would likely not grant consent for their data to be used.

On the other hand, CNTI’s analysis finds that proposals and laws that ban the use of AI for surveillance, as some countries have contemplated, would likely improve the safety of journalists and their sources. For example, the EU AI Act bans AI systems that “create or expand facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage.” While this represents a step in the right direction, the law does have exemptions for national security. Some countries have taken advantage of this; Hungary, for example, allowed the police to use biometric surveillance to identify participants in LGBTQIA+ public events.

Public information and awareness

Out of the 188 documents we reviewed, 76 address this issue directly. At least two documents from each region directly touch on this issue.

Many provisions for broad public awareness include journalists among their audiences, providing up-to-date sociotechnical knowledge that could inform stronger reporting. For example, Serbia’s AI strategy includes plans to organize seminars on AI, information security and big data specifically for journalists. Other policies offer similar information to all adults.

Documents that recognize the importance of journalism as a vehicle for public awareness are varied in their strategies. Lesotho’s draft policy encourages stakeholders to do outreach with a diverse spectrum of media outlets, acknowledging the importance of news without raising concerns about press independence. On the other hand, Egypt’s strategy expressly calls on the media to share “positive news of AI,” perhaps suggesting a bid to influence coverage. No document we reviewed calls for governments to spend advertising dollars to place public awareness campaigns in news media.

Recommendations

The inclusion or exclusion of these seven topics does not necessarily make a proposal “bad” or “good” overall or for journalism and the digital information space. There are many important considerations for AI policy proposals, of which journalism is just one. It is one, though, that CNTI finds incredibly important to functioning societies.

If an independent, diverse news media and open internet are not protected in the AI era, these new regulations could potentially criminalize journalism, threaten news business models, contribute to information disorder and prevent the public from accessing a diversity of fact-based news. The solution is not to call out journalism by name in every AI proposal, as that can have unintended consequences for the field, but it is essential that policymakers see journalists as important stakeholders in AI discussions and consider journalism’s viability as they develop future proposals. Likewise, it is important that news organizations and journalists see themselves as key stakeholders and thoroughly engage in thinking through and discussing the future of AI regulation.

The analysis surfaces a few key areas in need of specific policy attention:

- 1. In AI proposals that address manipulated content, it is important that policymakers work towards methods that protect certain journalistic uses in ways that do not enable government censorship or determination of who is or is not a journalist. This is far from an easy task and may mean the best path is no legal policy at all. Either way, it is critical to fully think through. Legislative efforts to prevent the spread of disinformation can sometimes have unintended consequences for journalism. For example, legislation that regulates the provision and sharing of manipulated content but does not include exceptions for journalism can lead to journalists being targeted for allegedly “spreading disinformation” for reporting on the existence of false information, such as a deepfake of an elected official, for using AI-manipulated content (like AI-generated avatars or voice-altered audio) to protect a source, or for covering information that those in power do not want covered. While not legally feasible in the U.S., carve outs for journalists in other countries could protect an independent news media, as well as a source’s right to privacy and willingness to share. But such carve outs, if not crafted extremely carefully, could also easily lead to greater censorship and criminalization. This takes coordinated, thoughtful deliberation. Alongside these discussions, journalists and news organizations should determine how best to convey their use of AI to the public, whether through labeling, watermarking or something else.

- 2. Bias audits and transparency measures are best implemented before a tool is deployed. To date, bias audits and transparency measures have often been reactions to issues that arise after deployment rather than components required prior to public launch. While not all issues can be identified in advance, more can be done before a tool is deployed, especially as these systems and our understanding of them matures. Policy can help lay out foundational requirements for audits, as well as for transparency, around how they are conducted and how issues are addressed, particularly for technology companies whose algorithms can have a social impact (i.e. if the algorithm uses personal data and makes or influences decisions that may have a significant impact on society or an individual).

One challenge is that as the number of AI developers proliferates (potentially including news organizations with sufficient resources), regulatory oversight needs can quickly balloon — a factor regulators would need to similarly prepare for in advance.

While audits and transparency requirements would not be a foolproof solution to addressing potential societal harms or inequalities tied to AI — including harms to journalism and the information space — they could help prevent or minimize them. They could also make it easier for journalists to report on potential bias as journalists currently rely on time- and labor-intensive reverse engineering.

- 3. Policymakers should ensure that AI working groups include journalism producers, product teams and engineers, alongside AI technologists, researchers, civil society and other relevant stakeholders. Policymakers face the challenge of attempting to legislate a technology that is constantly evolving and has wide-reaching consequences. As such, it is important that they meet with diverse stakeholders to ensure that they properly understand the technology they are trying to govern, as well as the consequences that both the technology and potential legislation could have on society more broadly. It is also critical that all at the table, including journalism leaders, are fully read-in and share the goal of collaboration, as such cooperation leads to the most optimal societal solutions. Expanded regional and international collaboration would also be valuable as AI regulation is a global challenge with cross-border implications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Monica Attard, Charlie Beckett, Niamh Burns, Claudia Del Pozo, Mohamed Farahat, Megan Gray, Assane Gueye, Jhalak Kakkar, Ashkhen Kazaryan, Tanit Koch, Prabhat Mishra, Amy Mitchell and Daniela Rojas for their thoughtful feedback on this report.

The authors also extend their gratitude to Greta Alquist for editing this report, Jonathon Berlin and Ryan Marx for designing the graphics and maps, Kurt Cunningham for creating the web design and the team at CETRA for their translation work.

Share