TL;DR

Table of Contents

Overview

AI chatbots — such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, Google AI Mode or the Washington Post’s “Ask the Post AI” — are software products which simulate human-like conversations and generate responses across a wide range of topics. While even their creators caution against using them as arbiters of fact, research consistently demonstrates that people increasingly rely on them for information about the world. Since the line between “information” and “news” is hardly clear-cut and information-seeking is also likely to include many topics where users of AI chatbots might previously have turned to news sources, news providers need an understanding of those broader informational habits.

This report provides a detailed snapshot of relatively early adopters and their use of AI chatbots to get information, including news. In October 2025, CNTI interviewed 53 people in India and the U.S. who use AI chatbots at least once a week and said they “keep informed about issues and events of the day” at least “somewhat closely.”

Why we did this

In 2025, a small, but almost certainly growing, segment of people around the world used AI chatbots as a source of news. In most of the countries included in the 2025 Reuters Digital News Report, between 5 and 10% of the population said they get news from AI chatbots at least sometimes. In the U.S., 7% said they get news from AI chatbots — about half as many as the 15% who said they get news from podcasts, which are considered a relatively established news platform. In India, 18% said they get news from AI chatbots at least weekly.

Like social media before it, it’s likely that AI chatbots and similar technologies will have profound effects on the information landscape, even if their designers did not originally intend for them to play (or foresee them playing) a large role in this space.

We set out to learn from relatively early adopters in the U.S. and India why and how they have incorporated AI chatbots into their information routines. We also aimed to understand how these findings might inform news providers refining strategies for maintaining and growing their audiences, both with their own AI chatbots and other tools.

Why we chose these two countries

- These countries represent the two largest markets for AI chatbots.

- Both India and the U.S. have highly concentrated news media ownership and increasingly politicized information habits.

- India is mobile-first in both behavior and infrastructure, while less than one in every five Americans rely primarily on smartphones for internet access.

- Overall, Americans express more negative attitudes towards AI than Indians do.

How we did this

Using the Respondent research platform, CNTI recruited adults who said they (1) use AI chatbots at least once a week and (2) “keep informed about issues and events of the day” at least somewhat closely. To learn about the breadth of use cases and opinions, we sought to maximize variation across demographics. See topline for details.

Our interview protocol incorporated a concurrent thinkaloud approach. After a series of questions about general news and information habits, we asked interviewees to share their screen while demonstrating how they use one or more AI chatbots of their choice. We also asked them to walk us through AI chatbot interactions from their history and their use of other platforms and tools, including news aggregators, social media and news sites. These methods provide richness and depth; however, it’s not possible to generalize about the frequency of behaviors from these interactions, so we have refrained from using quantitative terms throughout this report.

CNTI’s analysis focused on reasons for seeking information identified by audience practitioners, the experience of interacting with AI chatbots and interviewees’ broader understanding of information.

The AI chat window terminal is a deeply personal space and the researchers in this project are incredibly grateful to interviewees who opened this safe space to them.

As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI. This project was financially supported by CNTI’s funders.

See “About this study” for more details.

Top-level findings:

CNTI found that most AI chatbot users currently use them to supplement their existing information repertoires, not to replace them entirely. They toggle back and forth between AI chatbots, news sites, search engines, official sources and more. We saw:

- Actionable information: Interviewees use AI chatbots to act on what’s happening and understand it, more than simply to know about it or to feel something about it.

- Personalization: AI chatbot users see these tools as fast, easy, personalized, customizable and friendly ways of getting information.

- Low understanding but higher trust: Few AI chatbot users have deep knowledge about the processes behind either journalism or AI chatbots. At the same time, interviewees express a general trust of AI chatbots alongside a general distrust of news media (outside of some users’ trust in their specific sources).

Which AI chatbot?

ChatGPT and Google’s AI tools (including Gemini, Google Assistant and Google AI Mode) were by far the most common AI chatbots used by our interviewees, with Microsoft Copilot third.

We saw three different ways interviewees decide which AI chatbot to use.

Loyalty and lock-in: Some interviewees are loyal to one AI chatbot over another, even if they only use free services. They have invested their time in getting used to one system, and in customizing its responses to meet their needs and preferences. Their long chat history both helps them receive personalized responses and makes it possible to look up an older query, unlike search engines.

Take what you can get: Some interviewees, even if they have a preferred AI chatbot, are willing to use any of several chatbots to maximize their free use. They have accounts for multiple AI chatbot services and turn from one to the next when they reach their use quota. A few interviewees said they are not yet sure which AI chatbot best meets their needs, so they follow a similar pattern.

Multiple specialized tools: Some interviewees use a complicated array of AI chatbots for different purposes. They expressed strong intuitions that one is better than the others at programming, writing emails, image generation or personal advice. Similarly, some interviewees use one AI chatbot for professional purposes and another for personal needs. However, these preferences are individual and idiosyncratic; no consistent patterns emerged.

More specifically:

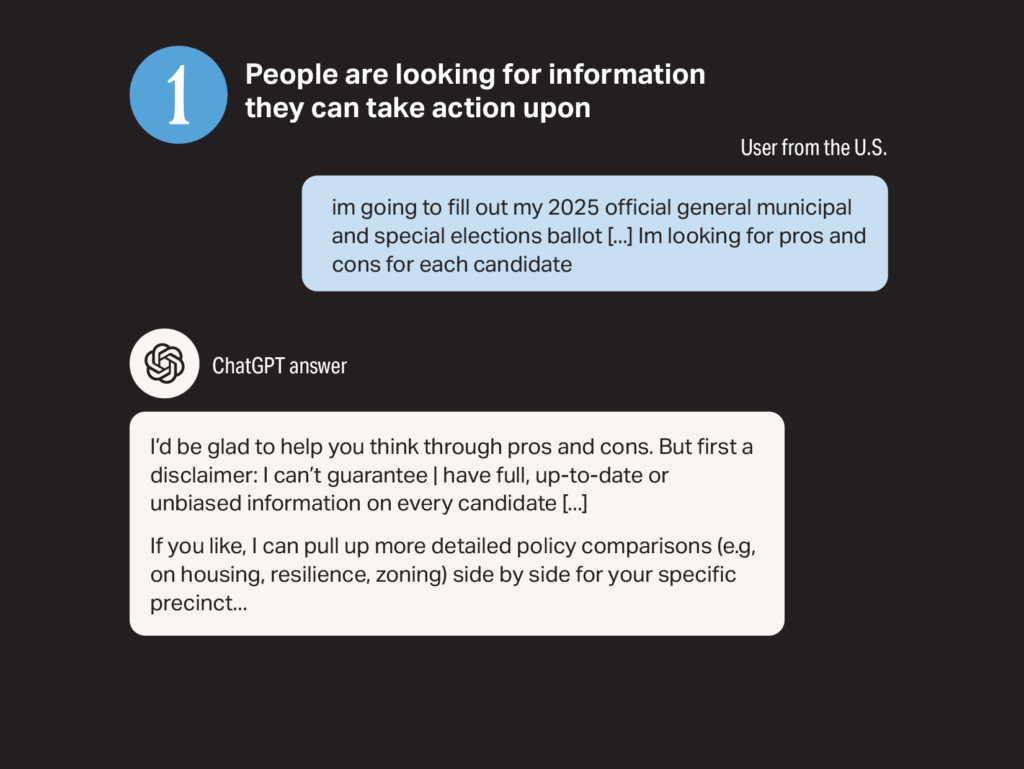

Interviewees use AI chatbots to act on what’s happening and to understand it, more than simply to know about it or to feel something about it.

What most drives AI chatbot use is the desire for information that helps people act. This is the most common use case for AI chatbots in both countries. Few interviewees want information for its own sake. Instead, they are looking to inform their choices and actions. AI chatbots stand out, especially in the U.S., for proactively helping people meet the need to act.

When it comes to knowledge for knowledge’s sake, interviewees in both countries use AI chatbots to supplement existing news habits, not replace them. No interviewee in either country said they rely solely on AI chatbots when they want to know what is happening. They do turn specifically to AI chatbots to learn what’s new about a story they are familiar with or to check a story that they don’t think is accurate (the latter now offered on some social media platforms, such as @grok on Twitter or Meta AI on Facebook).

Both U.S. and Indian AI chatbot users turn to them for context that is often absent in traditional news media. Many interviewees said that news stories often start in the middle, with background information buried or difficult to find. They find AI chatbots helpful for understanding who a public figure is, how another country’s legal system works and the history of Israeli-Palestinian relations — all contexts that news stories sometimes take for granted.

Emotional stimulation and entertainment are low information priorities. The “need to feel” does not seem to be a focus for our interviewees in either country, and did not come up much in our conversations. Interviewees do engage emotionally with AI chatbots, but only rarely with the information itself.

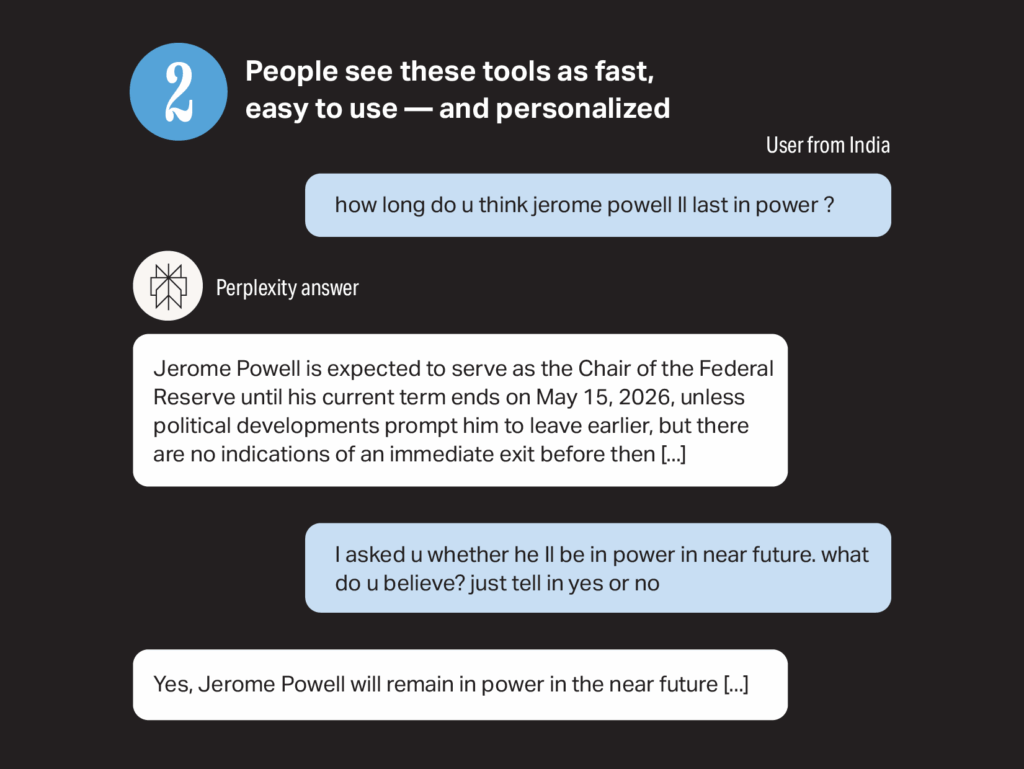

Interviewees see AI chatbots as a fast, easy, personalized, customizable and friendly way of getting information.

💬 They find the clean and structured presentation of information easy to process and enjoyable to read. This includes layout features such as bullet points, short headers and strategic bolding of generated text; short sentences and simple language; and the absence of noise such as advertisements, sidebars, paywalls and more — although this design feature could well change as revenue models develop.

💬 They say AI chatbots are a faster and more efficient way to get information than either search or website browsing. Numerous interviewees noted ways that AI chatbots save them time, which is especially valued for tasks they find tedious, like comparing information from multiple websites.

💬 They like being able to tailor content to their desired level of understanding. Interviewees often ask the AI chatbots to simplify complex topics or provide additional detail, allowing them to “zoom” to the right granularity for their needs. Some interviewees have used this feature to help teach their children difficult concepts or to have something explained in simpler language.

💬 They like the encouragement and upbeat tone AI chatbots bring to interactions. Many interviewees emphasized the consistent, affirmational and upbeat tone of AI chatbots. Several also noted that they feel comfortable asking chatbots questions they might avoid with a person for fear of being judged.

💬 They expressed concern about privacy and surveillance, but their behavior does not strongly reflect it. While interviewees in both countries expressed concerns about their prompts or inputs not being secure, their primary strategy is to avoid inputting personal details and medical or financial information.

Few interviewees have deep knowledge about the processes behind either journalism or AI chatbots. At the same time, they expressed generally positive attitudes towards AI chatbots alongside generally negative ones towards news media.

ℹ️ Most interviewees rely on at least a few news outlets in addition to AI chatbots, but almost none expressed an understanding of journalistic methods. The word “credible” came up repeatedly as a factor in selecting outlets. But when asked how one determines credibility, almost nobody could articulate it concretely. Instead we heard vaguely worded ideas about political slant.

ℹ️ Interviewees lack clear vocabulary to describe how AI chatbots process information and generate language, so they default to using language that describes human processes like “thinking” and “reading.” Many interviewees discussed what AI chatbots “know” or “think.” For some it is a mental shortcut, but for others it seems to represent misconceptions about how AI chatbots process text.

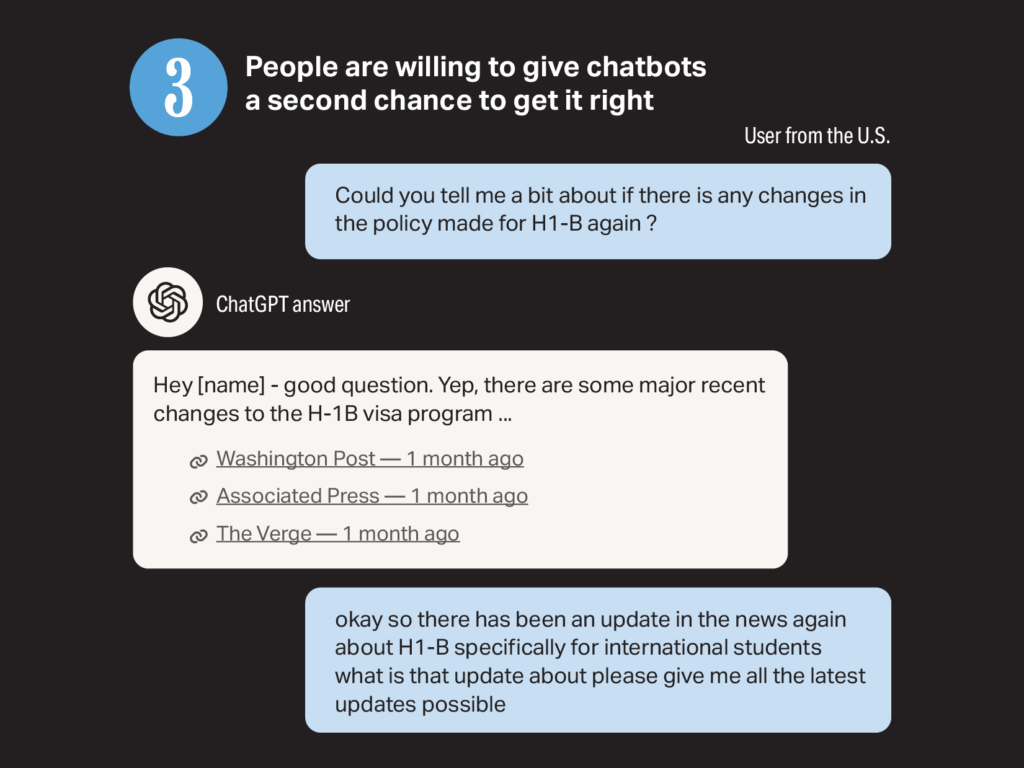

ℹ️ Interviewees expressed generally negative attitudes towards news media products and generally positive ones towards AI chatbots, even as they understand little about the underlying process of either. Beyond the specific sites and sources they themselves prefer, most expressed a broadly negative view of the news media, citing concerns like bias, commercial interest and sensationalism. In contrast, the same interviewees are forgiving of and persistent with AI chatbots when given a wrong answer.

ℹ️ The presence of cited and linked sources tends to be taken as an assurance of accuracy in AI chatbot outputs; interviewees rarely feel the need to click through. In most cases, interviewees assume that responses accurately reflect the linked sources. Interviewees’ opinions about the credibility of sources is largely transferred to the AI chatbot output, regardless of fidelity to those sources. Further, many Indian interviewees view AI chatbots as neutral aggregators with low levels of bias.

ℹ️ Two distinct factors tend to trigger a verification process: either the outputs contradict users’ assumptions or the stakes are high. Interviewees rely on gut instinct to decide what to verify. When looking into legal procedures or specific legal rights, we saw interviewees confirm the output of AI chatbots with official sources like the government or law firms.

ℹ️ When they do verify outputs, there is no consensus about the best way to do so. Although methods vary, multiple interviewees from both countries compare responses to the same question from two different AI chatbots. Some interviewees compare answers with search engines, social media or trusted individuals. Others limit the AI chatbot’s sourcing to “verified” or “evidence-based” references, assuming the output is consistent with the linked material.

ℹ️ Past experiences of inaccurate or outdated information did not deter them from future use. Many interviewees mentioned concerns about outdated, inaccurate or partial information. However, no interviewees described these concerns as a deal breaker that kept them from using AI chatbots.

ℹ️ In the search for unbiased information, interviewees are divided between those who worry about bias in AI chatbots and those who see AI chatbots as less biased than other sources of information — but neither bring deep knowledge into their opinions. Interviewees in both countries raised concerns about bias, but while some worried about bias in AI chatbots, others saw them as less biased than other sources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Mitchell for ongoing intellectual mentorship, partnership and leadership; Nupur Chowdhury, Rahul Dass, Kyong Mazzaro, Amy Mitchell and Nikita Roy for their thoughtful feedback on this report; Jonathon Berlin and Kurt Cunningham for web and graphic design; Angelica Ruzanova for support with transcription and data processing; and Greta Alquist for editing this report.

Share